A Lucky Child: A Memoir of Surviving Auschwitz as a Young Boy (19 page)

Read A Lucky Child: A Memoir of Surviving Auschwitz as a Young Boy Online

Authors: Thomas Buergenthal,Elie Wiesel

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General, #United States, #Biography, #Social Science, #Personal Memoirs, #Europe, #History, #Historical, #Military, #World War II, #World War; 1939-1945, #Holocaust, #Jewish Studies, #Eastern, #Poland, #Holocaust survivors, #Jewish children in the Holocaust, #Buergenthal; Thomas - Childhood and youth, #Auschwitz (Concentration camp), #Holocaust survivors - United States, #Jewish children in the Holocaust - Poland, #World War; 1939-1945 - Prisoners and prisons; German, #Prisoners and prisons; German

From our balcony on the Wagnerstrasse, I could look over the garden on to the street below. The street — Hainholzweg — was

a popular pedestrian route leading into the countryside east of the city. It attracted many Göttingen residents, particularly

on Sundays, when entire German families would pass our house on their way to and from their walks. I would observe them from

our balcony with envy and hatred. Here were fathers and mothers, grandfathers and grandmothers, walking with their children

and grandchildren — people who, for all I knew, had killed my father and grandparents! As I contemplated these scenes of happy

Germans enjoying their lives as if nothing had happened in the recent past, I longed to have a machine gun mounted on the

balcony so I could do to them what they had done to my family. It took me a long time to get over these sentiments and to

recognize that such indiscriminate acts of vengeance would not bring my father or grandparents back to life. It took me much

longer to realize that one cannot hope to protect mankind from crimes such as those that were visited upon us unless one struggles

to break the cycle of hatred and violence that invariably leads to ever more suffering by innocent human beings.

By the time I arrived in Göttingen, I probably had no more than half a year, if that, of formal education, all of it in that

Polish school in Otwock. I was therefore not ready to be enrolled in a German school with children my age. After making some

inquiries, Mutti found a retired high school teacher who tutored me for a little over a year. During that year, I made up

the six or seven years of school I had missed. My tutor, Otto Biedermann, had been expelled from Upper Silesia when it was

taken over by Poland and came to Göttingen as a refugee. He was a wonderful teacher who, probably more than any of the teachers

I had thereafter, introduced me to the joy of learning. I would come to him every morning for a period of two hours, then

work on the homework he would assign, which he corrected the next day. Initially, of course, he had to teach me how to read

and write — the basics of what children learn in the first couple of grades — before he could introduce me to all the other

material I would have learned if I had been able to attend school like other children my age. That meant that Mr. Biedermann

had to make sure that I studied the following subjects, among others: German, English, history, geography, and mathematics.

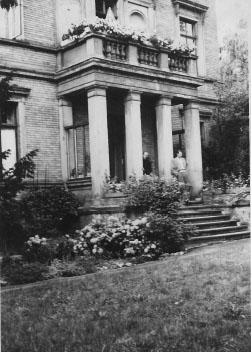

The balcony in Göttingen, where Thomas fantasized about mounting a machine gun

To improve my reading skills, Mr. Biedermann introduced me to the books of Karl May, the famous German writer of Wild West

books set in America that have captivated German children since the late nineteenth century, when they first appeared. My

reading skills increased dramatically as I devoured these books, learning all about cowboys and Indians and the American frontier

from an author who had never set foot in that country, but whose imagination and research made up for his lack of firsthand

knowledge. His books were filled with suspense, making it very difficult for me to put them down. Once I had significantly

improved my reading skills with Karl May’s books, it proved easier for Mr. Biedermann to get me to read other books and thus,

gradually, introduce me to the works of German literature that students my age had to read at school.

To improve my writing skills, he insisted that I write a brief essay every morning, describing what I had seen on my way from

my home to his. Under normal circumstances, it would take me about fifteen minutes to walk to his house. Since I would soon

run out of new things to report unless I varied my route, I got up earlier and earlier each morning to look for new ways to

reach his home. On the way, I would see parts of town I had never seen before. I encountered all kinds of people in the streets

and would try to guess who they were and where they were going. In those days, the streets of Göttingen, like those of other

German cities, still provided ample evidence of the terrible human suffering the war had visited on ordinary Germans. I would

see amputees, people whose faces had been disfigured by burns in the most bizarre ways, and some who had been blinded in one

or both eyes. Many of these individuals still wore all or part of their faded military uniforms. I would pass people who,

judging from their demeanor and clothing, looked like refugees. These daily discoveries made it easier to write the essays

Mr. Biedermann demanded of me and led to interesting discussions about contemporary realities that I would never have encountered

in school.

Mr. Biedermann once told Mutti that teaching me was an experience like none he had ever had. On the one hand, he told her,

I was a child who lacked even the most rudimentary educational background and needed to be tutored as if I were a six year

old; on the other hand, I had the life experience and maturity of a grown-up and could discuss subjects with him that no child

my age would normally be aware of or interested in. While learning German and European history, I would ask him about life

during the Nazi period and the reasons why he thought the Nazis had come to power, whether he had known any Nazis and what

kind of people they were. I wanted to know about his expulsion from Upper Silesia and whether he blamed the Poles or Hitler

for what happened to him and the other refugees. When studying geography, we talked about places I knew, countries I would

want to live in, what types of people made up their populations, the foods they grew, and the animals that could be found

there. Learning was fun with him, and I missed that sort of learning very much when I eventually entered school.

The only subject Mr. Biedermann did not feel competent to teach me was math — he had alerted Mutti to that fact and suggested

that she find me a math tutor — but since I had no interest in or talent for math, I was pleased that we neglected that subject

for some time until Mutti contracted a university student to provide me with the math background I needed to be ready for

school.

When I returned to Göttingen for a brief visit a few years after emigrating to the United States, one of the first people

I wanted to see was Mr. Biedermann. I had so much to tell him. He was interested in a great many things, and I knew that he

would want to hear about my studies in America, about life there, about the books I was reading, and so on. When I called

his home, I learned that he had had a stroke and was in the hospital. Of course, I went to visit him there. He recognized

me as I walked into his room, and while he could not speak, he squeezed my hand and held on to it for a long time. I am sure

that he knew that I had come not only to say good-bye but to thank him for laying the intellectual foundation for the life

I was destined to live.

There were two high schools for boys in Göttingen in my time (in those days schools were still segregated by gender): one

emphasized classical studies, such as Latin and ancient Greek; the other, which is now known as the Felix-Klein-Gymnasium,

focused on modern languages and contemporary subjects. When Mr. Biedermann decided that I was ready for school, I opted for

the Felix-Klein-Gymnasium and was admitted some time in 1948.

*

I was very pleased that I was admitted to the grade that I would have been in had I entered primary school with my classmates.

That made it much easier for me to become fully integrated into the life of the school.

I was the only Jewish student in the school. That had one great advantage: it meant that I was allowed to play in the school

yard during the one or two hours a week that religion was taught. As a rule, a Protestant clergyman or theologian would teach

this course to the Protestant students in my class, and a Catholic priest to the Catholic students. I was excused from the

religion course because, it was explained to me, there was no rabbi in town to teach me. Of course, I was delighted not to

have to attend any religion classes. Not surprisingly, some of my classmates envied my special status, since they too would

have loved to have been excused from taking religion.

None of my classmates had ever met a Jew, but, as some told me later, they had seen Nazi cartoons depicting Jews as dark-skinned,

alien-looking people with long crooked noses, black beards, and rapacious faces that were intended, because of their caricatured

ugliness, to illustrate the repulsive character of Jews. That is probably why some of my classmates asked, on first learning

that I was Jewish, whether I really was a Jew, for, as they put it, “You do not look like one.” Others were surprised that

I was good at sports, quite strong, and not afraid to defend myself when challenged by the class bullies. They had obviously

been exposed to Nazi propaganda that described Jews as weaklings, cowards, and lacking all aptitude in sports. Soon, though,

after the initial awkwardness and the novelty of having “a real Jew” in their class, I was accepted by my classmates as one

of them, and, what is more, I gradually came to feel that I was indeed one of them. I never heard any anti-Semitic remarks

from my fellow students, not even when I got into the typical schoolboy shoving matches with one or the other of them, nor

did I ever sense that they harbored anti-Semitic feelings that they were hiding from me. But as I reflect now on those years,

I am struck by the fact that I do not remember any of my classmates or my teachers asking about my life in German concentration

camps, even though it was no secret that I spent the war years in these camps. Was it that they did not want to hear about

my past, or did they believe that I would find it painful to talk about it? I do not know the answer.

Although my classmates accepted me, I could not help but feel that my presence made some of my teachers rather uncomfortable.

Quite a number of them had been members of the Nazi party. After the war, they had to submit to the denazification process

instituted by the occupation authorities and had to be cleared before they were allowed to teach again. I do not know how

many former teachers had failed to pass this process, but the impression current at the time was that many a real Nazi — in

contrast to the innocuous “

Mitläufer,

” or “fellow traveler,” one who had joined the Nazi party not out of conviction but for economic or other reasons — slipped

through the denazification net and was reinstated. In these early postwar years, most of these people were afraid to voice

their opinions. It was not surprising, therefore, that I was not subjected to any overt anti-Semitism, although I sensed that

some of them were always on guard because I was in their class and because of their own past. They carefully avoided expressing

their own opinions on certain “sensitive” issues that came up in class. I had the feeling, and that is all it was, that some

of them may have been denazified without ever eschewing their Nazi views. Only once did some of these sentiments come to the

fore. During a class discussion, and I no longer remember in which class it was, the teacher burst out with a harangue about

the Allied bombing of Hamburg and the large loss of life. It was barbaric and unprecedented, he claimed. I raised my hand

and asked, “What about the German bombing of London? Shouldn’t we also speak about that? And what about all the people who

were murdered in Nazi concentration camps?” Well, the man turned crimson and gave some explanation that equated the concentration

camps to the Allied bombings, which prompted me to walk out of the classroom, a totally unheard of step in a German school

in those days. My mother, of course, immediately complained to the school’s director, and the teacher apologized in due course

and said that I had misunderstood him. It was clear to me, though, that he apologized only for fear of losing his job. One

of my mother’s friends who had lived in Göttingen during the war chided her for not seeking the teacher’s dismissal because

the man was, as her friend put it, “

ein alter

Nazi” (a committed Nazi) who should never have been allowed to teach again.

We learned a great deal of history in our school, but it was mainly ancient and medieval German and European history. Contemporary

history was simply ignored. Not only were the Second World War, its causes, and the rise of Hitler never discussed but neither

was the First World War, which, if I remember correctly, seemed too current a subject to be dealt with. That was in sharp

contrast, of course, to the impressive efforts made in later years by the West German education authorities, who drastically

revised their school curricula to permit and encourage students to confront the past honestly and to foster a democratic spirit

of openness. Regrettably, that was not the case when I was at school in Göttingen. I was struck by the difference when I came

to the United States and enrolled in an American high school in 1952. Being used to the oppressive discipline that in those

days still reigned in German schools, I found the atmosphere in my American school almost too free and undisciplined. What

most impressed me, though, was the freedom that American teachers tolerated and encouraged when it came to the expression

of student views on almost any subject under discussion. We had a large number of student clubs and associations with elected

officers in my American high school; a schoolwide student government with a panoply of officers; and annual elections for

all those offices with election campaigns, pamphlets, and speeches mirroring American political elections. Whatever one might

think of the academic quality of American high school education, the American classroom struck me as a veritable incubator

of a democratic way of life, something the German classroom in my day certainly was not.