A More Perfect Heaven (33 page)

Read A More Perfect Heaven Online

Authors: Dava Sobel

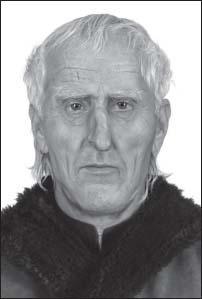

Copernicus the man has gained iconic status as well. Statues of him proliferate, especially in Poland, where his image has frequently appeared on stamps, coins, and banknotes. His very bones became the goal of an archaeological dig begun in the summer of 2004 under the stone floor of the Frombork Cathedral, where searchers eventually unearthed the skull and several bones of a seventy-year-old man that seemed to answer his description. The skull was just a fragment—the cranium without the mandible—but its age and resting place near the altar of St. Wenceslaus (now called Holy Cross) provided strong clues. Police forensic artists, accustomed to portraiture based on partial descriptions, parlayed the chinless skull into a full face with a big, broken nose and jutting square jaw. After a perpetual Copernican youth fostered by the single image of him in his prime, the sudden weight of years distorted the astronomer’s looks beyond recognition. In the photo released to news services, the old man wore a fur-collared jacket in a red reminiscent of his portrait jerkin.

Subsequent examination of the skull suggests that the dent over the right eye is an arterial depression typical of many skeletons—not a match for the scar depicted in Copernicus’s portrait. No one doubts, however, that the skull belonged to him.

The scant bones underwent DNA analysis, for anticipated comparison with the latter-day descendants of Copernicus’s nieces. The most convincing piece of evidence emerged from a secondary trove of remains—the nine hairs that had worked their way into Copernicus’s oft-consulted copy of a 1518 calendar of eclipse predictions, held in Uppsala with the rest of the books the Swedish Army took from the Varmia library during the Thirty Years’ War.

When Gingerich heard about the hairs found in the

Calendarium Romanum Magnum

, he imagined they might belong to him, given the number of times he had bent his own head over that same book to study Copernicus’s notations in it. But DNA testing of the four suitable hairs showed that two of them made convincing matches with a well-preserved molar in the Frombork skull. When the scientists reported their results in 2009 in the

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

, they said that certain genes seen in the remains were typical of blue-eyed individuals. The police photo had depicted Copernicus with brown eyes, the same color as in the Torun portrait, adjusted for age-related fading.

Working from bone fragments, Polish forensic artists imagined the face of their famous countryman as a man of seventy years—Copernicus’s age at death.

The second burial of Canon Nicolaus Copernicus took place in Frombork on May 22, 2010. Unlike the first funeral, the pageantry of this one drew a large crowd, and included a Mass led by the Primate of Poland, the country’s most highly honored bishop. Not since Copernicus’s Uncle Lukasz Watzenrode carried St. George’s head here in 1510 had this cathedral seen a more triumphant procession focused on funerary relics.

A new black granite tombstone with a stylized golden Sun and planets now flanks the earlier memorial installed in the cathedral in 1735 (to replace a still earlier epitaph destroyed during wartime). Beyond such plaques, statues, and other public tributes, his fellow “mathematicians” continue to afford Copernicus their professional recognition. The first cartographers of the Moon named a large lunar crater for him in the 1600s, and Space Age explorers launched an orbiting astronomical observatory called

Copernicus

in 1972. For the 537th return of his birthday, on February 19, 2010, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry announced the naming of super-heavy atomic element number 112 “copernicium” (symbol Cn) in his honor.

Every time the

Kepler

spacecraft, currently in orbit, detects a new exoplanet around a star beyond the Sun, another ripple of the Copernican Revolution reverberates through space. But the counterrevolution that sprang up in immediate reaction to Copernicus’s ideas also continues to make waves. State and local governments still claim the right to control what can be taught of scientific theories in classrooms and textbooks. A so-called museum in the southeastern United States compresses the Earth’s geological record from 4.5 billion to a biblical few thousand years, and pretends that dinosaurs coexisted with human beings.

Copernicus strove to restore astronomy to a prior, purer simplicity—a geometric Garden of Eden. He sacrificed the Earth’s stability to that vision, and pushed the stars out of his way. To contemporaries who doubted the grandiose dimensions of the heliocentric design, Copernicus replied,

“So vast, without any question, is the divine handiwork of the most excellent Almighty.”

In the century after his death, the Inquisition struck that line from his text. Although Copernicus clearly meant to express confidence in the Omnipotent’s ability to transcend ordinary proportion, the censors saw the statement as an ungrounded confirmation for an Earth in motion.

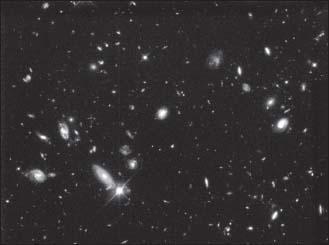

When the Earth moved despite the Church’s objections, Copernicus became symbolic of a new fall from grace. Because of him, humanity lost its place at the center of the universe. He had initiated a cascade of diminishments: The Earth is merely one of several planets in orbit around the Sun. The Sun is only one star among two hundred billion in the Milky Way—and relegated to a remote region far from the galactic center. The Milky Way is just one galaxy in a Local Group of neighbors, surrounded by countless other galaxy groups stretched across the universe. All the shining stars of all the galaxies are as nothing compared to the great volume of unseen dark matter that holds them in gravitational embraces. Even dark matter is dwarfed by the still more elusive entity, dark energy, that accounts for three quarters of a cosmos in which the very notion of a center no longer makes any sense.

A small corner of today’s known universe, depicted in this Hubble telescope Deep Field image, is many times more vast than the once-shocking distance Copernicus allowed between Saturn and the stars. To use his word, the extent of his entire cosmos was “negligible” compared with the many millions of light years separating our Milky Way from the galaxies beyond.

It would be impossible to overstate the generosity of the historians, directors, and people of good cheer who have helped me relive the Copernican Revolution.

Professors Owen Gingerich, André Goddu, Michael Shank, Noel Swerdlow, and the late Ernan McMullin lent their authority in history and astronomy, along with earnest encouragement. The first three also reviewed the draft chapters of this book to correct my mistakes.

Directors Gerald Freedman, Langdon Brown, and Isaac Klein read and commented on numerous drafts of the play, always with constructive advice.

In Poland, Janusz Gil, Tomasz Mazur, Krzysztof Ostrowski, and Jaroslaw Wlodarczyk variously welcomed, guided, mentored, interpreted, and read drafts for me. I am also grateful to Stanislaw Waltos for facilitating permission to view the Copernicus manuscript in Krakow.

At Uppsala, Tore Frängsmyr opened the doors to Copernicus’s personal library.

The John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation provided grant support, with kind attention from Edward Hirsch and André Bernard at Guggenheim, Doron Weber at Sloan, Annie MacRae as the Sloan Project manager at Manhattan Theatre Club, and Paige Evans.

The Naked Stage, the Manhattan Theatre Club, the New York State Writers Institute Authors Theatre, and the University and Teatr Lubuski of Zielona Gora (Poland) staged readings of the play in progress.

Astrologer Elaine Peterson cast and interpreted horoscopes for Copernicus and Rheticus.

Stalwart supporters including my agent, Michael Carlisle; my editor and publisher, George Gibson; my daughter, Zoe Klein; my brothers and sister-in-law, Stephen, Michael, and Pamela Sobel; my cousins Celia Michaels and Barry Gruber; my friends Diane Ackerman, Jane Allen, Will Andrewes, K. C. Cole, Doug Garner, Mary Giaquinto, Joanne Julian, M. G. Lord, Doug Offenhartz, Rita and Gary Reiswig, Lydia Salant, Margaret Thompson, and Alfonso Triggiani have all proved especially helpful, often just by being who they are.

1466

Peace of Torun concludes the Thirteen Years’ War between the Prussian cities of Poland and the Knights of the Teutonic Order.

1473

Copernicus born,

February 19.

1484

Copernicus’s father dies.

1489

Copernicus’s uncle Lukasz Watzenrode elected Bishop of Varmia, February 19.

1491

Copernicus enters Jagiellonian University in Krakow.

1492

Ferdinand and Isabella expel the Spanish Jews.

Columbus voyages to the New World.

1496

Copernicus studies canon law in Bologna.

1497

Copernicus appointed canon in Frauenburg.

1500

Copernicus spends several months in Rome, gives lectures on math.

1501

Copernicus and brother, Andreas, attend Varmia Chapter meeting in July.

Copernicus enrolls as medical student at Padua in October.

1502

University of Wittenberg founded.

1503

Copernicus receives doctor of canon law degree at Ferrara, May 31; becomes bishop’s secretary and personal physician at Heilsberg in the fall.

1504

Copernicus observes great conjunction in Cancer, notes that Mars is ahead of—and Saturn behind—predicted positions.

1508

Copernicus conceives the geokinetic idea, probably begins work on his heliocentric model.

1509

Copernicus publishes his Latin translation of the Greek letters of Theophylactus Simocatta in Krakow.

1510

Copernicus leaves the bishop’s service, moves to Frauenburg, distributes his

Brief Sketch

as a pamphlet.

1512

King Sigismund I marries Barbara Zapolya in Krakow, February 8.

Uncle Lukasz dies in Torun, March 29, after attending the king’s wedding.

1513

“Doctor Nicholas” purchases bricks and lime to build an observing platform.

1514

Georg Joachim Iserin (later Rheticus) born, February 16.

1515

Copernicus offers opinion on calendar reform to Pope Leo X.

Full text of Ptolemy’s

Almagest

appears in print for the first time.

1516

Copernicus begins three-year term as administrator, November 11.

1517

Copernicus writes his

Meditata

on currency problems, August 15.

Martin Luther posts his 95 Theses in Wittenberg.

1518

Andreas dies in November.

1519

Teutonic Order invades Braunsberg, December 31.

1520

Grand Master Albrecht’s troops set fire to Frauenburg, January 23.

1521

War with Teutonic Knights ends; peace treaty signed, April 5.

1522

Copernicus introduces currency reform based on his essay of 1517.

Other books

London Harmony: Feel the Beat by Erik Schubach

A Certain Latitude by Mullany, Janet

High-heeled Wonder (A Killer Style Novel) (Entangled Ignite) by Flynn, Avery

The House On Willow Street by Cathy Kelly

Playing Knotty by Elia Winters

Rockinghorse by William W. Johnstone

Deathscape by Dana Marton

The Master Of Strathburn by Amy Rose Bennett

Learning Curves by Elyse Mady

Sunruined: Horror Stories by Andersen Prunty