A Most Immoral Woman

Read A Most Immoral Woman Online

Authors: Linda Jaivin

For my parents

In Which, Following a Useless Day, Our Hero Finds Himself Irresistibly Drawn to Trouble

In Which Is Noted the Difficulty of Overheating a Room in North China in Winter

In Which Morrison and Miss Perkins Arrive at the First Pass Under Heaven

In Which Morrison Finds Lionel James in the Queen’s House and Resists Duty in the Name of Temptation

In Which Bedlow Stays, Granger Goes and Our Hero Endures a Veritable Fusillade

In Which Our Hero Hesitates and Is Lost, Following Which He Receives a Most Concerning Summons

In Which Morrison Endures a Most Curious Conversation

In Which Morrison Meets a Young Lady in Men’s Clothing and Learns That They Have Interests in Common

In Which Our Hero Battles with the American Military for Access to the Front

In Which the Correspondents’ Quest for Access Is Afforded a Definitive Answer

In Which the Correspondent Corresponds and at Least One Love Story Ends Happily

In Which It Is Seen That Heat Lingers Even as the Earth Cools

In Which, By Way of Afterword, We Note That It Is True That…

Our Hero Finds Himself Irresistibly

Drawn to Trouble

The ravishing Miss Perkins, eyes luminous, unfurled her sultry smile. ‘The famous Dr Morrison,’ she purred. ‘We meet at last.’

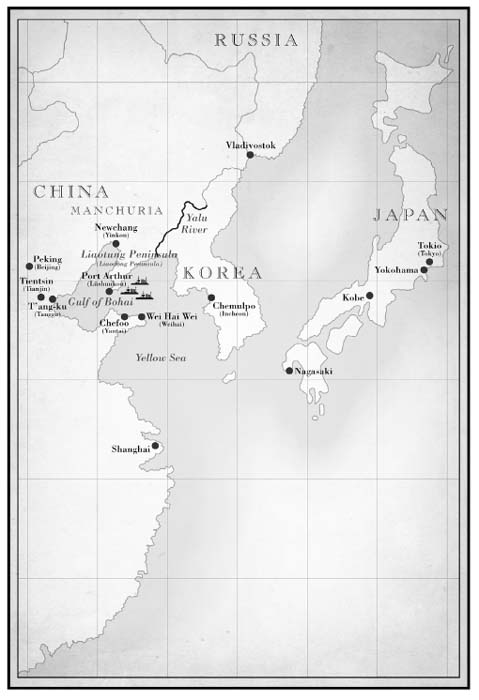

The day had not begun with so much promise. George Ernest Morrison had awoken in a second-rate hotel in the Manchurian town of Newchang, oppressed by a thick, cotton-wadded quilt and a sense of futility. The whistle and crack of whip birds in a sun-drenched dream of the Antipodes resolved into the hard smack of a crop on a horse’s flank, and the crunch of eucalyptus bark underfoot gave way to the clatter of cart wheels on cobblestones. Morrison blinked open his eyes. His rheumatism frisked in the cold; he scissored his aching legs under the covers. Through the window he saw that the sky lay low and gunmetal grey. It was the last day of February, 1904.

A donkey brayed. A child cried. A man swore softly. Morrison lifted his head, still heavy with sleep, and listened. Even after seven years of living in China, his Mandarin was not perfect. But

it did not take linguistic genius to comprehend profanity or despair. The first refugees, he guessed, of the war.

The Russo-Japanese War had broken out three weeks earlier when Japan’s navy staged a surprise attack on the Russian fleet at Port Arthur, the deep-water port on the tip of Manchuria’s Liaotung Peninsula. The news had delighted Morrison. As the China correspondent for

The Times

of London and a loyal colonial, George Ernest Morrison was convinced that it was in Britannia’s interests to see its ally Japan chase the Russians out of northern China. In his telegrams for

The Times

he had agitated at length to sway world opinion in favour of the Japanese cause.

Since the war had taken off, however, Morrison’s life had unexpectedly ground into stasis. Months before, he had written to his editor in London, Moberly Bell, to say he was thinking of leaving China on account of poor health. His complaints, which he did not hesitate to enumerate, included arthritis, a persistent catarrh, and occasional nasal haemorrhages due to a spear wound that had nearly killed him when he had attempted to tramp across Papua New Guinea as a young man. So when the war—

his

war—had finally broken out, Bell assigned other men to cover the conflict and ordered Morrison to remain in Peking. There he could help the other correspondents and cover the big picture without further endangering his health—or employment. How Morrison regretted the querulous moment of nose-bleeding, joint-aching weakness that had prompted his complaint to Bell.

Bored, Morrison had broken away from Peking to come to Newchang, a neutral port on the northwestern corner of the contested peninsula, hoping to find information and excitement. After two days he’d found little of either, only too many Russian

soldiers and the perfidious British profiteers who supplied them with coal and arms.

Morrison threw off the fusty quilt and stretched. His long legs were cramped from the effort of sleeping in a bed made for a much shorter man. It was a familiar problem and one he considered a metaphor for his life of late.

He cleared his throat and called out for his Boy.

Even at this hour, Morrison’s voice rang resonant and muscular. Pepita, Spanish señorita and his lover when he had worked as a surgeon in the mines of Rio Tinto, once told him that it was the voice of a matador. The description pleased him. For several years after Morrison left Spain, Pepita had proclaimed her undying love in purple ink on perfumed paper. He only ever answered the first letter. He hadn’t thought about Pepita in recent times but in his mind’s eye he now saw black, fragrant hair swinging over a supple waist; slender forearms; brown, eager nipples. As much as he tried, he could not remember her face except in parts: a flash of smile, an arched eyebrow.

At forty-two, Morrison was old enough to know how quickly red-hot passion could turn to ash, but still young enough to find it astonishing. Pepita had captured his affection not long after he recovered it from Noelle, a Parisian grisette who had escaped not only with his heart but his money and pride as well. There had been women before them, of course, and many since. His most recent affair, with the wife of a British customs official from Wei Hai Wei, had been of a relatively calm and cynical nature. He had not experienced feral attachment in a long while.

Pepita. Sweet Pepita.

The door squeaked open. It was not the time to think about Pepita.

Morrison watched Kuan, his Boy, move about the room, stoking the fire and refreshing the wash basin with hot water. Kuan laid out his master’s clothes and gave them a quick brush, his movements an economical blend of grace and efficiency. Morrison took comfort in the familiar sound of Kuan’s felt-soled shoes padding over the carpets, and the swish and rustle of his quilted robes. He liked his servant; Kuan was clever, curious and resourceful, his English more than competent. Morrison wondered sometimes where Kuan’s life might have led if he had not been a foundling raised by missionaries to serve in foreign homes. He marvelled, not for the first time, at the young man’s inborn poise and dignity. Sometimes he felt like a clumsy giant in comparison.

‘Kuan. Go outside and learn what you can from the refugees, especially those from Port Arthur. What they’ve seen—number of Russian and Japanese ships, type of guns, how many supply wagons, how many dead. Whatever they can tell you.’

‘

Ming pai

. I understand.’ Kuan quickly finished setting out his master’s razor, strop and flannel. His long plait had been coiled around his neck for warmth and convenience whilst he performed his chores. Now that he was going out, Kuan unwound it so that it hung straight and proper down the back of his long robe. ‘Oh,’ he added, ‘Colonel Dumas is already at breakfast.’

Morrison acknowledged this with a nod. Charles Merewether Dumas, a British military attaché whose job, not unlike his own, was to gather intelligence, was Morrison’s friend and travelling companion. ‘Tell him I’ll be down shortly.’

Scraping the light ginger stubble from his chin, Morrison noticed that the once proud lines of his jaw were softening. Though his complexion was still the colour of the sun and sand of

his native land, grey was starting to pepper his beard and temples. Less than a month had passed since his forty-second birthday, yet his neck, like his waist, was already beginning to thicken. Morrison caught his own gaze in the looking glass. It was pale and merciless.

‘You’re looking chipper this morning,’ Dumas observed as Morrison joined his table in the breakfast room.

‘I don’t feel chipper,’ Morrison replied, ‘so it’s quite remarkable that you should say so. In truth, I was feeling rather downspirited. As I regarded my figure in the looking glass, I concluded that although I remain a bachelor, I’m fast acquiring the body of a married man.’

Dumas laughed.

Morrison narrowed his eyes reproachfully. ‘I’m pleased to have so amused you—even if it is at the expense of my own pride.’ He surveyed the menu, feigning annoyance.

‘I wasn’t laughing at you. In fact, I’d assumed that my own rather teapot-like physique was the basis for your observation about married men. I’m only two years your senior and wedded but ten, yet I’m an exemplar in this regard.’ Dumas twirled the tip of his moustache around his finger; he had magnificently luxuriant whiskers and a habit of playing with them as though they were a small and attention-starved pet. ‘You ought to know that my wife says that of all the Western men in China, you are still the most handsome. She is not promiscuous with her compliments, either. Handsome is certainly not a word she has ever used in relation to my good self. You really do need to find yourself a wife.’

‘Now you sound like Kuan. He insists that 1904, being the Year of the Dragon, is propitious for marriage. But you both forget one crucial detail. I have no prospects. Your own wife appears to be my only admirer, and she is taken.’

‘That is a matter for debate,’ Dumas replied with a doleful expression. ‘But seriously, I cannot credit for a moment that you would have any difficulty finding a wife if you really wanted one.

The

Dr Morrison. Hero of the Siege of Peking. Renowned overlander, author, medical doctor, eminent China correspondent of

The Times

of London. Respected, influential, etcetera, etcetera.’

‘You’re mocking me.’

‘Not at all. I should think eligible maidens would be queuing up.’

‘Piffle. I’m a man of restricted means and poor health. The only maidens who ever show any fondness for me are elderly rejects with yearnings and false teeth—the sort who suffer from indigestion and clammy hands and feet.’

Dumas chortled. ‘That is not what I hear, and you do not believe a word of it, either. On the basis of the stories you’ve told me yourself, I believe that you have made more conquests than Britannia. Were you not relating a most amusing story about a Brunhilde to me just a few months ago?’

‘I have never gone with a woman called Brunhilde.’

‘Yet there was a German actress whose private performances you enjoyed with astonishing frequency over a period of two days whilst her dunderhead of a husband conducted his business in the same city. Melbourne, wasn’t it?’

‘Her name was Agneth. And it was Sydney. But your power of recall is otherwise frightening. Remind me never to tell you anything I do not myself wish to remember. The point is, of all

these women, not one still shares my bed. Those whom I found most amusing always returned to their husbands in the end. The others turned out to be boring and spiritless—a pity, for they were the only ones guaranteed not to turn into faithless neurotics after marriage. To be perfectly honest, I would not mind a steady supply of affection and sympathy in my life. It does not, however, appear to be forthcoming from available sources.’

‘Oscar Wilde once said—and nothing in my own experience would disprove it—that marriage is the triumph of imagination over intelligence. Maybe you just need to apply less intelligence and more imagination to your prospects.’

Morrison regarded the plate that the waiter placed before him. ‘Do you think these are duck eggs?’

‘No, just the eggs of very small chickens. It’s wartime.’

‘The war only broke out two weeks ago. Hardly enough time to affect the growth of chickens.’ He pushed aside his plate. The subject of marriage pained him more than he let on. He extracted his fob chain from the pocket of his waistcoat and checked the time. ‘We’d better hurry. We are nearly late for our first useless appointments of the day.’

‘Remind me,’ the soldier-diplomat sighed. ‘My excellent memory does not extend quite as well to our shared professional concerns.’

‘I am to see a Japanese who will treat me with the utmost courtesy but who will tell me nothing. You will call on an uncivil Russian who will share with you all manner of intelligence as interesting as it is mendacious. Following that, we will both meet a Chinese who will, with great anxiety, ask

us

what is going on in the war being fought by the other two over the northern portion of his own country. Then Kuan will convey to us the unreliable

testimony of excitable refugees. Finally, having been denied permission to go to the front by our Japanese friends, we will catch a train back to China proper, stopping at Mountain-Sea Pass for the night. Along the way, we will exchange notes and ruminate on the futility of it all. I shall wonder what I can possibly write in my telegram for

The Times

and you will contemplate, with equal despair, your report to the Foreign Office.’

The morning’s activities transpired as Morrison had predicted. By early afternoon, the correspondent, the military attaché and the servant stood on the platform at Newchang Station. Morrison’s nose burned with cold and his toes ached numbly inside his thick woollen socks and leather boots. The saturnine sky began to dissolve into snow just as a whistle announced the train’s arrival.

The journey took most of the afternoon. The men read aloud from their notebooks: missionaries were withdrawing their womenfolk from the peninsula; Russian troops had threatened to torch an entire town if the Chinese army, which had arrived to protect the frightened residents, did not leave immediately; two hundred and ninety-eight mines set by Russians and Japanese to blow up one another’s armadas were adrift in open water, threatening shipping.

‘A stupid day,’ Morrison summed up, ‘spent in the accumulation of petty detail.’

Dumas grimaced. ‘What will you focus on in your telegram?’

‘It hardly matters. Whatever I write, those peace lovers in Printing House Square will indubitably temper it before publication.’ Morrison knew that it was not just out of consideration for his health that Bell had given the task of reporting on the war to other correspondents. His editor was wary of his partisanship. Japan

might be an ally of Britain, but Britain’s official stance was neutral and Bell was determined to see

The Times’s

coverage reflect that.

By the time the train pulled into the old garrison town of Mountain-Sea Pass at the eastern terminus of the Great Wall, the men were fatigued into companionable silence and the sun had set on an undulating white landscape.

Outside the station, a row of flickering lanterns indicated the presence of ricksha men. As the train disgorged its passengers, the runners jumped to their feet, shaking out their legs and shouting for custom. A Japanese invention, the ricksha had taken off in China where the press of more than four hundred million people in a parlous economy made men cheaper than horses. Now Kuan was trying to procure three of them for even less still.

At last the three men were bouncing along on the thinly padded seats towards their hotel outside the walls of the Chinese town, rough blankets tucked around their knees for warmth. Morrison glanced over at his companions. The lanterns swinging at their feet illuminated their faces from below like characters from a ghost story and captured his runner’s breath as a long, thin cloud. The runners’ felt boots, bound with rope for traction, slapped the frozen ground. Icicles hung from the curlicue limbs of a scholar tree and a dog barked beside a gloomy farmhouse. Ahead, the full moon was rising over the crenellated parapets of the Great Wall. If Morrison were a different sort of person, he might have remarked that the night seemed full of poetry, mystery and magic. But his mind was filled with more prosaic thoughts of war, dinner and the prospect of a good night’s sleep.