A Nest for Celeste (18 page)

Read A Nest for Celeste Online

Authors: Henry Cole

T

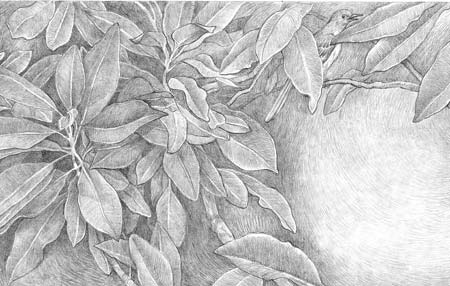

he summer was ending. Cicadas droned lazily in the surrounding treetops. The mockingbird, after a hiatus during the heat of dog days, was singing again from inside the magnolia. A golden haze spread across the sky to the west.

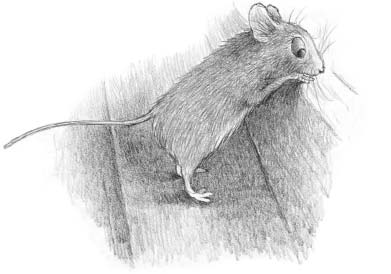

Celeste woke from a long, deep sleep to the sound of a horse whinnying. She looked out her window.

Down below, three horses stood in the shade of a pecan tree. Men were loading supplies and belongings onto one of the horses; Celeste recognized Audubon and Mr. Pirrie among them. She saw the dark shape of the gray cat sitting idly among the roots of the pecan tree, looking bored.

At least now I can safely head back to Joseph’s room,

she thought.

As the men worked, Celeste noticed that more than the usual amount of supplies and goods were being loaded—too many things were being strapped to the back of the packhorse, including large, flat bundles carefully wrapped. “Those are the paintings,” Celeste whispered to herself.

Then her heartbeat quickened as she saw Joseph coming from inside the house, carrying a saddlebag. She could hear the men talking.

“That everything, Joseph?” Audubon asked.

“Yes, sir. Well, almost everything.”

“Almost?”

“Yes, sir. I can’t find Little…I can’t find my mouse.” He eyed the gray cat under the magnolia. “I can’t just leave her here.”

Audubon frowned at Joseph. “It’s a mouse. Tighten those satchel straps. We’re ready to go. Monsieur Pirrie, we bid you

adieu

.”

In a heartbeat Celeste realized what was happening; Joseph was leaving, and he wasn’t coming back.

The supplies he brought back from New Orleans were in preparation for a journey away from here.

She felt panicky. She leaped from the sill, her feet flying as fast as a honeybee’s wings down the attic steps, out through the knothole, then to Joseph’s old room. It seemed lighter, empty. The rows of jars and plant stems were gone, as were the large sheets of paper and drawing supplies. Joseph’s familiar smell barely lingered in the air.

Celeste quickly climbed the drapes. From this sill, a floor lower, she had a better view of the yard below.

Audubon and Joseph were checking and rechecking the ropes and leather straps. Then they turned to shake hands with Mr. Pirrie.

Celeste knew she could never get there in time. And even if she could, would Joseph see her in the grass? Wouldn’t she just be flattened under the feet of the horses? Or chased across the grass by the cat? Or sniffed out by Dash and eaten in one gulp?

She could barely hear the voices of the men, but she knew they were saying words of parting. She saw Joseph lift his head toward his old bedroom window and imagined that his gaze lingered for a second. She raced back and forth along the windowsill. “Joseph! Joseph!” she squeaked.

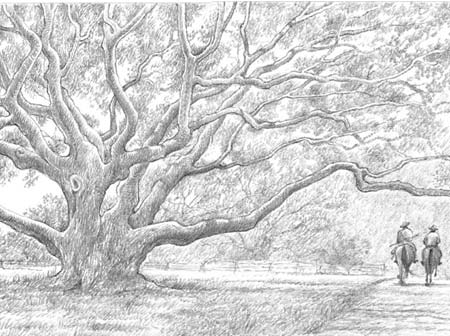

But a moment more and both Joseph and Audubon were astride their horses, Dash tagging behind. Joseph kept looking back over his shoulder toward the house. Celeste watched them ride down the lane. She watched until the bend in the road hid them from view and they disappeared.

She made her way back up the attic steps. Home.

She positioned her chair on the sill, then sat watching as the sun touched the treetops.

She thought about Joseph: his skill at making a drawing, at making the painting of a leaf or flower look real, as though it were resting on the paper.

She thought about his kindness: The gentle way he

gave her a home in his pocket.

She pondered: Was it worth the feelings of sadness and melancholy to make a friend and then lose him? Would she rather not have the heartache of losing a friend and not have the memory of friendship? No, she decided, no.

She heard a fluttering sound from above her head.

She looked up to see a small bird peering down at her from the edge of the roof.

“Hello!” Celeste called up.

“Hello!” the bird chirped back. “Are you Celeste?”

Celeste smiled. “Yes, that’s me! Who are you?”

With another fluttering of wings the little wren dropped to the sill. Her feathers were honey brown, and her eyes twinkled.

“My name is Violet,” she said. “Pardon me for dropping in like this. I’m a friend of Cornelius.”

“Cornelius! How wonderful! Welcome!” Celeste hurriedly scrambled to drag out another chair from the living room. “Is he all right? Have you heard from him?”

“Oh, he’s quite a ways from here by now; I’m sure of that. We won’t see him again until spring comes back. But he told me about you before he left. He said I’d find you here.”

“I’m going to miss Cornelius this winter.”

“He said you were the very best there is at finding dogwood berries,” Violet said.

Celeste smiled. “Well, I don’t know about that!”

“He told me you were a music lover.”

“Cornelius is the one who made me realize how much I liked music.”

“And he said you might like having a friend around this winter,” said the wren.

“Well, he was right about that.” Celeste chuckled.

She set out her blue-and-white china plates and filled them with tidbits from the cupboard.

“You have a beautiful nest,” Violet said admiringly. “How did you come to live here?” And Celeste told her the story, all the way from the beginning.

The two sat gazing contentedly at the surrounding landscape. They heard the creaking wagons returning

from the fields, the jingle and clank of horse harnesses. Lafayette, silhouetted against the sky, flying with familiar flaps and glides, was returning from a fishing foray along the river; Celeste waved.

She smiled.

She thought about the summer, of surviving a terrible thunderstorm and of flying in a basket.

She thought of Mr. Audubon, and of secretly helping create a work of art.

She thought of Joseph, and how love can start with something as simple as the gift of a peanut.

She thought of Cornelius and Lafayette; and as she offered a berry to Violet, she thought how good it was to have friends.

Osprey and Weakfish

(1829)

J

OHN JAMES AUDUBON (1785–1851) was a master at creating powerful images filled with beauty and emotion, even though his subjects were merely birds. He spent most of his life traveling over much of eastern North America, often on foot, carrying paints and paper, sketching constantly, documenting the native plants and animals as they existed in the early 1800s.

Before Audubon came along, wildlife artists painted their subjects in static and stiff poses, as though mounted in a display case. But Audubon filled each of his paintings with a zest and vigor that makes them seem to fly across the page. This was years before photography, so his paintings are a record of animals and plants of another century. And his artistic ability was self-taught, which makes his work even more amazing.

The landscape that inspired him looked much different than it does today. Roads were scarce; this was long before the age of the automobile. Completion of the transcontinental railroad was still decades away. The population of the United

States was only around ten million; that’s only about four people per square mile if you sprinkled them evenly over the country.

Today, the population is more than thirty times that, a density of nearly eighty people per square mile.

Audubon walked or rode horseback through vast tracts of forest that stretched from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mississippi River, through deep woods of ancient, towering trees hundreds of years old. Thousands of miles of pristine rivers and millions of acres of woodland habitat had not yet been replaced or polluted by farms and industry. That would come later.

Along those rivers roamed animals we wouldn’t expect to see there today: cougars and jaguars, wolves and bison, lynx and elk. Audubon encountered birds that are now extinct, such as the ivory-billed woodpecker, the Carolina parakeet, and the passenger pigeon mentioned in this story.

For nearly two years he traveled with an assistant, Joseph Mason. Joseph was a great help to Audubon; and although only a teenager (he was thirteen when he started out with Audubon), he became very skilled at painting botanical subjects, particularly wildflowers. Many of the beautiful backgrounds of plants and flowers in the bird portraits are credited to Joseph.

Audubon’s life as a painter and naturalist was often difficult: He was separated from his family for long periods of time

while out gathering specimens for his paintings, frequently living hand-to-mouth. No one was paying him to paint birds; it was his idea and his passion. But he managed to paint more than four hundred North American bird species, each one a carefully rendered portrait—from the dowdy field sparrow to the flamboyant flamingo.

It’s a bit ironic that his paintings depict such lively, animated birds. His artistic methodology would be illegal today! He killed nearly all of his subjects, using a shotgun, and did indeed use wire to position the dead specimens into lifelike poses. His images were huge, all of them life-size; the pages of his

Birds of America

were nearly three feet tall, so large that two people were needed to turn the pages carefully, and special tables were required to display the books.

In 1821 Audubon lived for about four months at Oakley Plantation, not far from New Orleans, Louisiana. To earn his room and board while staying at Oakley he gave the plantation owner’s daughter, Eliza Pirrie, dancing and drawing lessons. By reading his journals, we know that Audubon was particularly charmed and inspired by the woods and bayous around Oakley and worked diligently on many of his paintings at the plantation.

The fictionalized events in the story of Celeste take place during those four months. Some of it is true: Joseph was indeed

shot while out flushing turkeys during a hunt, for example; and Audubon did keep a live ivory-billed woodpecker and a live osprey for a time.

But did Joseph have a field mouse for a companion? Was Eliza’s old dollhouse tucked away in the attic? I like to think so.

I am so fortunate to have honest, encouraging, thoughtful, and talented friends who have spent many hours of their time reading drafts of this story and kindly giving me helpful suggestions. Many, many thanks to Quinn Keeler, Laura Behm, Nancy Powell, Roland Smith, Margaret Elliot, and Nan Fry.

Thank you, Amy Ryan, for your marvelous enthusiasm and energy with the design and layout.

And to my wonderful editor and friend, Katherine Tegen, with much love and appreciation, I dedicate this book.