A Night to Remember

Read A Night to Remember Online

Authors: Walter Lord

Walter Lord

To My Mother

2 “There’s Talk of an Iceberg, Ma’am”

3 “God Himself Could Not Sink This Ship”

4 “You Go and I’ll Stay a While”

5 “I Believe She’s Gone, Hardy”

6 “That’s the Way of It at This Kind of Time”

7 “There Is Your Beautiful Nightdress Gone”

8 “It Reminds Me of a Bloomin’ Picnic”

9 “We’re Going North Like Hell”

10 “Go Away—We Have Just Seen Our Husbands Drown”

I

N 1898 A STRUGGLING

author named Morgan Robertson concocted a novel about a fabulous Atlantic liner, far larger than any that had ever been built. Robertson loaded his ship with rich and complacent people and then wrecked it one cold April night on an iceberg. This somehow showed the futility of everything, and in fact, the book was called

Futility

when it appeared that year, published by the firm of M. F. Mansfield.

Fourteen years later a British shipping company named the White Star Line built a steamer remarkably like the one in Robertson’s novel. The new liner was 66,000 tons displacement; Robertson’s was 70,000. The real ship was 882.5 feet long; the fictional one was 800 feet. Both vessels were triple screw and could make 24-25 knots. Both could carry about 3,000 people, and both had enough lifeboats for only a fraction of this number. But, then, this didn’t seem to matter because both were labeled “unsinkable.”

On April 10, 1912, the real ship left Southampton on her maiden voyage to New York. Her cargo included a priceless copy of the

Rubáiyát

of Omar Khayyám and a list of passengers collectively worth two hundred fifty million dollars. On her way over she too struck an iceberg and went down on a cold April night.

Robertson called his ship the

Titan;

the White Star Line called its ship the

Titanic.

This is the story of her last night.

Titanic

1) 11:40

P.M

. - The bridge thanks the crow’s nest for reporting the iceberg.

2) 12:00 Midnight - Lawrence Beesley notices the deck has started to tilt.

3) 12:30

A.M.

- John Jacob Astor slices open a life belt to show his wife what’s inside.

4) 12:45

A.M.

- The first rocket is fired.

5) 12:55

A.M.

- Major Peuchen proves a yachtsman can be a seaman

6) 12:55

A.M.

- Fifth Officer Lowe bawls out the head of the steamship line.

7) 1:10

A.M.

- Mrs. Isidor Straus refuses to leave her husband.

8) 1:15

A.M.

- “If they are sending the boats away, they might just as well put some people in them.”

9) 1:20

A.M.

- Ben Guggenheim appears in evening clothes to go down like a gentleman.

10) 1:25

A.M.

- Steward Ray remembers he persuaded a family to sail on the

Titanic

11) 1:30

A.M.

- Fifth Officer Lowe has to use his gun.

12) 1:35

A.M.

- First Officer Murdoch prevents a rush on Boat 15.

13) 2:05

A.M.

- Edith Evans gives up her chance in order to save a married woman with a family.

14) 2:10

A.M.

- Wireless Operator Phillips’ life belt is almost stolen.

15) 2:15

A.M.

- The band plays “Autumn.”

16) 2:18

A.M.

- Colonel Gracie recalls a trick he learned at the seashore.

1) 11:40

P.M.

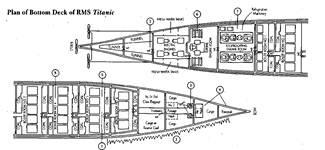

- Engineer Hesketh and Fireman Barrett have to jump through the watertight door.

2) 11:40

P.M.

- Iceberg tears 300-foot gash, ripping open first six watertight compartments.

3) 11:50

P.M.

- Water is swirling round foot of spiral stairs.

4) 11:50

P.M.

- Water pours in so fast that escaping air forces up hatch cover and hisses out of forepeak tanks.

5) 12:45

A.M.

- Engineer Shepherd breaks his leg.

6) 12:45

A.M.

- Electrician Alfred White brews some coffee.

7) 1:00

A.M.

- Greaser Thomas Ranger turns off 45 fans.

8) 1:15

A.M.

- Stoker Fred Scott frees a trapped friend.

9) 1:20

A.M.

- The sea pours in on Trimmer George Cavell.

“Another Belfast Trip”

H

IGH IN THE CROW’S

nest of the New White Star Liner

Titanic,

Lookout Frederick Fleet peered into a dazzling night. It was calm, clear and bitterly cold. There was no moon, but the cloudless sky blazed with stars. The Atlantic was like polished plate glass; people later said they had never seen it so smooth.

This was the fifth night of the

Titanic

’s maiden voyage to New York, and it was already clear that she was not only the largest but also the most glamorous ship in the world. Even the passengers’ dogs were glamorous. John Jacob Astor had along his Airedale Kitty. Henry Sleeper Harper, of the publishing family, had his prize Pekingese Sun Yat-sen. Robert W. Daniel, the Philadelphia banker, was bringing back a champion French bulldog just purchased in Britain. Clarence Moore of Washington also had been dog shopping, but the 50 pairs of English foxhounds he bought for the Loudoun Hunt weren’t making the trip.

That was all another world to Frederick Fleet. He was one of six lookouts carried by the

Titanic,

and the lookouts didn’t worry about passenger problems. They were the “eyes of the ship,” and on this particular night Fleet had been warned to watch especially for icebergs.

So far, so good. On duty at 10 o’clock … a few words about the ice problem with Lookout Reginald Lee, who shared the same watch … a few more words about the cold … but mostly just silence, as the two men stared into the darkness.

Now the watch was almost over, and still there was nothing unusual. Just the night, the stars, the biting cold, the wind that whistled through the rigging as the

Titanic

raced across the calm, black sea at 22½ knots. It was almost 11:40

P.M.

on Sunday, the 14th of April, 1912.

Suddenly Fleet saw something directly ahead, even darker than the darkness. At first it was small (about the size, he thought, of two tables put together), but every second it grew larger and closer. Quickly Fleet banged the crow’s-nest bell three times, the warning of danger ahead. At the same time he lifted the phone and rang the bridge.

“What did you see?” asked a calm voice at the other end.

“Iceberg right ahead,” replied Fleet.

“Thank you,” acknowledged the voice with curiously detached courtesy. Nothing more was said.

For the next 37 seconds, Fleet and Lee stood quietly side by side, watching the ice draw nearer. Now they were almost on top of it, and still the ship didn’t turn. The berg towered wet and glistening far above the forecastle deck, and both men braced themselves for a crash. Then, miraculously, the bow began to swing to port. At the last second the stem shot into the clear, and the ice glided swiftly by along the starboard side. It looked to Fleet like a very close shave.

At this moment Quartermaster George Thomas Rowe was standing watch on the after bridge. For him, too, it had been an uneventful night—just the sea, the stars, the biting cold. As he paced the deck, he noticed what he and his mates called “Whiskers ’round the Light”—tiny splinters of ice in the air, fine as dust, that gave off myriads of bright colors whenever caught in the glow of the deck lights.

Then suddenly he felt a curious motion break the steady rhythm of the engines. It was a little like coming alongside a dock wall rather heavily. He glanced forward—and stared again. A windjammer, sails set, seemed to be passing along the starboard side. Then he realized it was an iceberg, towering perhaps 100 feet above the water. The next instant it was gone, drifting astern into the dark.

Meanwhile, down below in the First Class dining saloon on D Deck, four other members of the

Titanic

’s crew were sitting around one of the tables. The last diner had long since departed, and now the big white Jacobean room was empty except for this single group. They were dining-saloon stewards, indulging in the time-honored pastime of all stewards off duty—they were gossiping about their passengers.

Then, as they sat there talking, a faint grinding jar seemed to come from somewhere deep inside the ship. It was not much, but enough to break the conversation and rattle the silver that was set for breakfast next morning.

Steward James Johnson felt he knew just what it was. He recognized the kind of shudder a ship gives when she drops a propeller blade, and he knew this sort of mishap meant a trip back to the Harland & Wolff Shipyard at Belfast—with plenty of free time to enjoy the hospitality of the port. Somebody near him agreed and sang out cheerfully, “Another Belfast trip!”

In the galley just to the stern, Chief Night Baker Walter Belford was making rolls for the following day. (The honor of baking fancy pastry was reserved for the day shift.) When the jolt came, it impressed Belford more strongly than Steward Johnson—perhaps because a pan of new rolls clattered off the top of the oven and scattered about the floor!

The passengers in their cabins felt the jar too, and tried to connect it with something familiar. Marguerite Frolicher, a young Swiss girl accompanying her father on a business trip, woke up with a start. Half-asleep, she could think only of the little white lake ferries at Zurich making a sloppy landing. Softly she said to herself, “Isn’t it funny … we’re landing!”

Major Arthur Godfrey Peuchen, starting to undress for the night, thought it was like a heavy wave striking the ship. Mrs. J. Stuart White was sitting on the edge of her bed just reaching to turn out the light, when the ship seemed to roll over “a thousand marbles.” To Lady Cosmo Duff Gordon, waking up from the jolt, it seemed “as though somebody had drawn a giant finger along the side of the ship.” Mrs. John Jacob Astor thought it was some mishap in the kitchen.