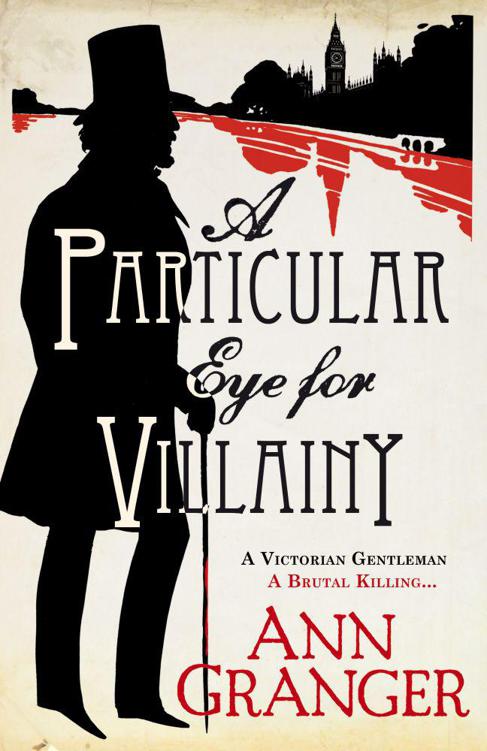

A Particular Eye for Villainy: (Inspector Ben Ross 4)

Read A Particular Eye for Villainy: (Inspector Ben Ross 4) Online

Authors: Ann Granger

Copyright © 2012 Ann Granger

The right of Ann Granger to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law, this publication may only be reproduced, stored, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, with prior permission in writing of the publishers or, in the case of reprographic production, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency.

First published as an Ebook by Headline Publishing Group in 2012

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

eISBN : 978 0 7553 8377 1

HEADLINE PUBLISHING GROUP

An Hachette UK Company

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

Ann Granger has lived in cities all over the world, since for many years she worked for the Foreign Office and received postings to British embassies as far apart as Munich and Lusaka. She is married, with two sons, and she and her husband, who also worked for the Foreign Office, are now permanently based in Oxfordshire.

As well as writing three previous Victorian mysteries featuring Inspector Ben Ross and Lizzie Martin, Ann Granger is also the author of the highly acclaimed Mitchell and Markby novels; the Fran Varady mysteries; and a brand-new crime series set in the Cotswolds featuring Superintendent Ian Carter and Inspector Jess Campbell.

Praise for Ann Granger’s Victorian mysteries:

‘Period colour is nicely supplied … This engrossing story looks like the start of a highly enjoyable series’

Scotsman

‘Murder most enjoyable’

Bournemouth Daily Echo

‘The book’s main strength is the characterisation and the realistic portrayal of London in the mid-19th century’

Tangled Web

‘Ann Granger has a keen eye and ear for the social nuances of the times. Readers are assured of a neat and rounded yarn to keep them guessing. Roll on volume three in this entertaining series’

Oxford Times

By Ann Granger and available from Headline

Inspector Ben Ross crime novels

A Rare Interest in Corpses

A Mortal Curiosity

A Better Quality of Murder

A Particular Eye for Villainy

Fran Varady crime novels

Asking For Trouble

Keeping Bad Company

Running Scared

Risking It All

Watching Out

Mixing With Murder

Rattling The Bones

Mitchell and Markby crime novels

Say It With Poison

A Season For Murder

Cold In The Earth

Murder Among Us

Where Old Bones Lie

A Fine Place For Death

Flowers For His Funeral

Candle For A Corpse

A Touch Of Mortality

A Word After Dying

Call The Dead Again

Beneath These Stones

Shades Of Murder

A Restless Evil

That Way Murder Lies

Campbell and Carter crime novels

Mud, Muck and Dead Things

Rack, Ruin and Murder

When Mr Thomas Tapley, a respectable but down-at-heel gentleman, is found bludgeoned to death in his sitting room, his neighbour Inspector Benjamin Ross of Scotland Yard rushes to the scene. Tapley had recently returned from abroad but little else is known about the elusive man. Then, on hearing the news of Thomas’s death, Mr Jonathan Tapley, QC, comes forward and the truth about his cousin’s tragic past slowly begins to emerge.

Meanwhile, Ben’s wife Lizzie is convinced that Tapley was being followed on the day he died and, with a bit of surreptitious questioning, she discovers that he received a mysterious visitor in a beautiful carriage a few days before his death.

As the list of possible suspects begins to mount, Ben can’t help wondering how much of the truth is being revealed and who would benefit most from Tapley’s unfortunate demise?

I would like to thank Radmila May, both for her friendship, and for her kindness in helping me research various points of the Victorian legal system, during the writing of this book.

Elizabeth Martin Ross

A FINE spring day in London isn’t to be compared with spring in the countryside but the city does its best. Its dusty trees are green with new shoots. A pall of smoke still hangs above the roofs but it is thinner than the evil black blanket smothering the streets in midwinter. Pedestrians are no longer muffled to the eyebrows now the sleet and biting winds have vanished. They look happier as they hurry about their business. After being the prisoners of our own homes most of the past months, this was all too tempting. I put aside any tasks, told Bessie our maid to do the same, and the pair of us set out for a good long walk to feel the warmth of the sun on our faces.

The river really didn’t smell too foul that day as we crossed it from the south side, where we lived, to the north. We have Mr Bazalgette and his new and improved sewer system to thank for not having to hold a handkerchief to our noses. My plan was to walk along the new embankment until Blackfriars and then, if not too tired, continue until we reached the looming fortress of the Tower. There we’d definitely turn back for home because we would have covered a fair

distance. Beyond that point, in any case, lay St Katherine’s dock on the upper pool of the port of London and the district of Wapping.

‘Wapping’, said Bessie firmly, ‘ain’t a place where a lady like you should go walking. Nor me, neither, come to that!’

She was right, of course. Wapping heaved with activity centred on the port and London docks. Seamen of all nations thronged its streets and taverns. Chandlers’ shops jostled opium dives. Cheap lodging houses neighboured brothels. Dead bodies were regularly pulled from the river at Wapping Stairs and not all of them had met their deaths by drowning. I know all this because I am married to an inspector of police, although happily he is based at Scotland Yard.

‘We might not get as far as the Tower,’ I said to Bessie as we stepped off the bridge. ‘But we’ll do our best.’

At that point we were hailed by a voice behind us. We turned to see Mr Thomas Tapley scurrying past the tollbooth, waving his battered umbrella in salutation. It didn’t look like rain, but Mr Tapley never left his umbrella behind when he sallied forth, every day, for what he liked to call his ‘constitutional’. He was a short man; so spindly in build it looked as if a breath of wind would bowl him over and send him tumbling along like a carelessly discarded sheet of newspaper. Yet his pace was always brisk. He was wearing what I shall always think of as his uniform: checked trousers and a frock coat once black but now faded to a bottle green as iridescent as shot taffeta in the sunshine. A hat with a low crown and broad curling brim topped his outfit. The style of headwear had been fashionable some twenty years earlier. I remember my father donning a similar hat before setting out

to make his house calls. It had cost him a pretty penny but my father had justified the expense. A doctor, he’d pointed out, should look prosperous or patients will think he’s little in demand and there must be a good reason. Tapley’s hat had suffered the passage of time and was spotted and scuffed, but it was tilted at a jaunty angle.

‘Good afternoon, Mrs Ross! A fine day, is it not?’ He answered his own question before I could. ‘Yes, a beautiful day. It fairly makes one’s heart sing! I trust you are well? Inspector Ross keeps well too?’

His wide smile crumpled his skin like a wash-leather; his eyes twinkled brightly and showed he had most of his teeth in reasonable condition considering his age. I supposed him in his sixties.

I assured him that Ben and I were both in good health and gave Bessie, walking beside me, a nudge to let her know she should stifle her giggles.

‘You are taking the air!’ observed Mr Tapley, bestowing another kindly smile on Bessie.

Ashamed, she made an awkward curtsy and mumbled, ‘Yes, sir.’

‘And you are right to take the opportunity,’ continued Tapley to me. ‘Exercise, dear madam, is of the greatest importance in the maintenance of good health. I never fail to take my constitutional, come rain or shine. But today one can only feel particularly fortunate!’

He made a theatrical sweep of the umbrella towards the river behind us, sparkling in the sunshine and dotted with shipping of all kinds, busily chugging up and down. There were lighters, coal barges, doughty little steam tugs, even a

vessel marked as belonging to the River Police, while wherries bobbed back and forth between them all, often, it seemed, avoiding collision by a miracle.

‘Our great city at work, on land and on river,’ observed Tapley, using the umbrella as a schoolmaster uses a cane or rule to point out chalked details on a blackboard. Seamlessly, he continued: ‘My regards to Inspector Ross. Tell him to continue his stalwart efforts to rid London of scoundrels.’

He tipped his hat, beamed, and walked on. We watched him skirt a small crowd that had gathered round a street entertainer, bounce across the road on his small neat feet and head north through the narrow streets leading up into The Strand.

‘He’s a funny old gent, ain’t he?’ observed Bessie disrespectfully but accurately.

‘He’s obviously fallen on hard times,’ I told her. ‘That’s not his fault – or we don’t know that it is.’

Bessie considered this. ‘You can see he’s a gent all right,’ she conceded. ‘He must have had money once. Perhaps he gambled or drank it away . . .’ Her voice gained enthusiasm. ‘P’raps he had a business partner who made off with the cash or perhaps he—’

‘That’s enough!’ I said firmly.

Bessie came to join Ben and me when we married and set up home. She has the stunted but wiry build of one raised ‘on charity’ with the quick wits and sharp instincts of a child of the city poor. She is as ferocious in her loyalty as she is in her opinions.

As for Thomas Tapley, no one knew very much about him. Bessie was not the only one to have speculated on what might

have brought him to reduced circumstances. He lodged at the far end of our street in a house that was not part of our recently built terrace but much older, here long before the railway came. When it was built there must have been fields around it. It was a four-square Georgian building with fine pediments, a little chipped and knocked about now, and an elegant door case. Perhaps it had once belonged to some prosperous merchant or even some country gentleman of independent means. It now belonged to a Mrs Jameson, the widow of a clipper ship captain.

The street had been surprised when she took in Thomas Tapley as a lodger six months or so earlier, because she was a lady with some claim to status. If she needed to let one of her rooms to supplement her income, she could have been expected to select a professional man for her tenant. But Mr Tapley was possessed of a certain charm and innocence of manner. For all his down-at-heel appearance, the street soon decided he was ‘an eccentric’ and approved his presence.

How odd it was that a chance meeting and a simple exchange of courtesies should draw both Bessie and me into a murder investigation. But no one could have guessed, that fine, bright spring morning, that we were among the last people to see Thomas Tapley alive, and to speak to him, before he met a violent death.

We did reach the Tower. The sun was so pleasant without being hot that we were surprised to find we’d come so far. We turned back conscious of a long walk home again. The river here was possibly even busier, with larger vessels. There were the colliers that had brought the coal on which London’s fires

and steam power depended. We saw a pleasure craft carrying some of the first day-trippers of the season and even, in the distance, the tall masts of a clipper ship that made me think of Tapley’s landlady. But it was a fleeting thought and poor Tapley was immediately out of my mind again.

We were growing weary as we approached Waterloo Bridge once more. The embankment here was always a busy spot, with passengers making their ways to and from the great rail terminus of Waterloo on the farther side by cab and on foot. Inevitably, street entertainers, peddlers of small items ‘useful for the journey’ or out-and-out beggars had stationed themselves here. They didn’t venture on to the great bridge itself because of the guardian of the tollbooth who wouldn’t have permitted it. The police, if they caught them, also moved them on. The offenders always came back. Being occasionally arrested for causing an obstruction didn’t deter them.

Bessie’s sharp eyes had spotted something. She tugged at my arm and hissed, ‘Missus! There’s a clown there. Do you want us to turn back?’

But by now I’d seen him too. He had taken up a pitch about ten yards ahead of us where it would be impossible to step on to the bridge without passing close by him. I remembered the small crowd earlier, when we crossed on our outward path. Perhaps it had been watching this same fellow. If so, the watchers had obscured him from my view. I could hardly have missed him otherwise, or have come across a greater contrast to shabby little Thomas Tapley. The clown’s brightly coloured form was unmistakable: a middle-aged man of portly frame clad in his ‘working uniform’ of a patched woman’s gown,

loosely cut, with a hemline a little below his knees revealing striped stockings and overlarge boots. A wide frill, a sort of tippet, was tied round his neck and reached his shoulders to either side. Over a garish orange wig with ringlets dangling about his ears, he had crammed a peculiar bonnet, very difficult to describe. It was rather like an upturned bucket, decorated with all manner of paper flowers and tattered ribbon bunches. The whole was secured with a wide ribbon tied in a bow beneath his double chin.

He was harmlessly engaged in juggling some balls, pretending to drop one and catching it at the last minute, while keeping up a shrill patter in a falsetto mimicking a woman’s voice. His antics didn’t bother me. It was his painted face: a dead white, eyes outlined with blacklead with long eyelashes drawn above, mouth coloured vivid scarlet with lips pursed as if about to bestow a kiss, and another large round scarlet spot on each of his puffy cheeks.

I’ve never liked clowns, though the word is inadequate to describe the real horror they inspire in me. I panic at the sight. My heart pounds and terror tightens my throat so I can barely swallow. I can hardly breathe. You’ll think me foolish but nothing so real can be dismissed as nonsense.

The abiding fear dates from an incident in my childhood. I was six years old. My nursemaid, Molly Darby, persuaded my father that I’d enjoy a visit to a travelling circus that had set up camp on fields at the edge of our town. My father was doubtful. As a doctor he knew the dangers of being in unwashed crowds. But there were no fevers running around the town at that moment and Molly insisted. ‘She’d love it, sir. Why, all the little ones do.’

She meant, of course, that she would love it.

My father, still hesitant, turned to me and asked if I’d like to go. Carried away by Molly’s assurances of the wonders I’d see, I told him I would. So my father agreed with the proviso that Mary Newling, our housekeeper, should go along with us. I think now he didn’t quite trust Molly’s motives, out and about with only a six year old as chaperone. He probably suspected an assignation with an admirer. If so perhaps he was right, for Molly’s face certainly fell when she heard that Mrs Newling was to be of our party. But she cheered up because we were at least going.

As for Mary Newling, it took an hour to persuade her. ‘It’s not a place any decent woman should be going. There will be thieves and vagabonds everywhere and folk doing things they shouldn’t!’ This last claim was accompanied by a meaningful glare at Molly.

She blushed but stood her ground. ‘Dr Martin says it’s all right.’

So, with Mary Newling still grumbling, off we set. I hopped along full of anticipation. If anything, Mary’s warning of vagabonds had made the trip more exciting. I wasn’t sure what a vagabond was, but it must be an interesting beast.

My enthusiasm flagged a little by the time we’d taken our places on a hard wooden bench in the huge tent. (‘The big top!’ Molly whispered to me. ‘That’s what it’s called.’) I had never been in such vast (to me) gathering. We had paid extra and it entitled us to sit at the very front. But from behind us came much argument and exchange of insult and profanity as the crowd heaved and pushed, fighting for the best vantage points. Mary Newling scowled and placed her large

work-worn hands over my ears, clamping my head in a vice. It was very hot and the air smelled bad.

We faced a circular area floored with sawdust called, said Molly importantly, the ring. It was empty but any moment wonderful sights would fill it.

‘We’re packed like herrings,’ groused Mary Newling, unimpressed, ‘and a lot of the folk here are strangers to soap and water, it seems to me. If a body were to be taken faint there’d be nowhere to fall. They’d have to lay the poor soul on that . . .’ She pointed to the sawdust floor.

Just then a band took up its place on a podium to one side. It was no more than a couple of fiddles and a trumpet-player, together with a man either banging on a drum or rattling an instrument of his own invention: a pole with various bits of metal attached. It made a wonderful racket when he beat the end of his staff on the ground. I was more than ready to believe Molly’s assertion that it was a proper orchestra.

When the orchestra fell silent, into the ring strode a fine moustachioed gentleman in hunting pink and dazzling white breeches. He saluted us with his top hat, bid us welcome and to prepare to be amazed. He then turned and pointed with his long whip to a curtained spot behind him.