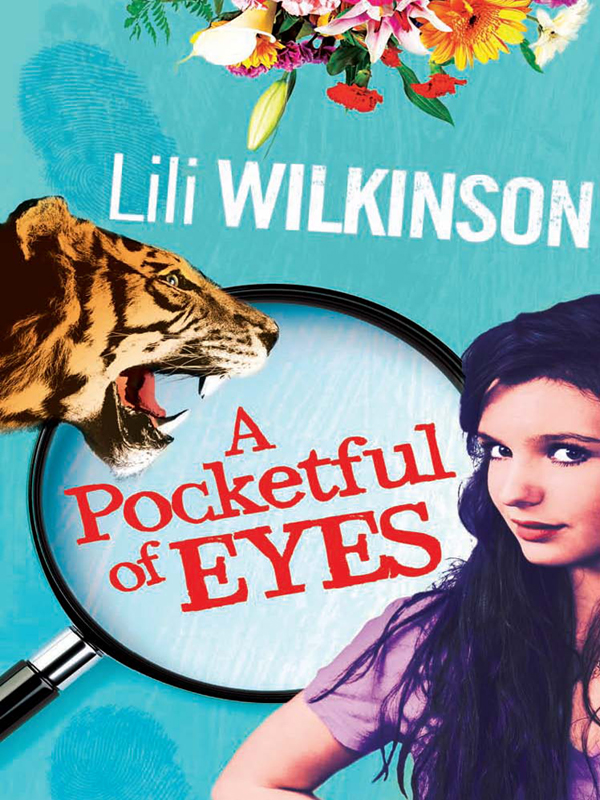

A Pocketful of Eyes

Read A Pocketful of Eyes Online

Authors: Lili Wilkinson

First published in 2011

Copyright

©

Lili Wilkinson 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The

Australian Copyright Act 1968

(the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or ten per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065 Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: [email protected]

A Cataloguing-in-Publication entry is available from the National Library of Australia www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74237 619 6

Cover photos by Britt Erlanson/Getty Images; Larry Lilac/Alamy; iStockphoto

Cover and text design by Lisa White

Set in 12/18 pt Adobe Garamond Pro by Bookhouse, Sydney

eBook production by

Midland Typesetters

, Australia

Printed in Australia by McPherson’s Printing Group

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Michael, who helped solve this mystery and many others

ON ENTERING THE TAXIDERMY LABORATORY

in the Melbourne Natural History Museum’s Department of Preparation on the morning of Thursday 13 January, at 9:25, Beatrice May Ross noticed six unusual things, all of which turned out to be of the utmost significance. The things (in no particular order) were:

1. The clock on the wall was three minutes slow, putting the time at 9:22.

2. On the third shelf from the right and four shelves down, a jar marked

EYES, REPTILE, S–M

was missing a lid.

3. Gus, the Head Taxidermist, was eating a wholemeal sandwich containing roast chicken, mayonnaise, alfalfa sprouts, plastic cheese, tomato and beetroot.

4. The beetroot was about to make a desperate bid for freedom and head for the neutral territory on the front of Gus’s bottle-green Natural History Museum hoodie.

5. Gus didn’t seem to be particularly concerned that Bee was running twenty-five minutes late (or twenty-two if you believed the clock on the wall).

6. There was a stranger in the laboratory.

The stranger was a young man, probably a couple of years older than Bee, and he was sitting at the spare desk next to Gus’s. He had artfully messy dark-brown hair, black-framed glasses and a cheeky glint in his eye that made Bee feel immediately hostile.

Gus made no attempt to introduce Bee to the stranger, or acknowledge her presence in any way, so she went to her desk and sat down. The possum lay sprawled in exactly the same position as it had been when she left the building last night.

Why was there a

boy

in her laboratory? The spare desk had previously been piled high with seagull wings and ice-cream containers marked Claws and plastics catalogues. Now it was cleared, and the boy was sitting there. He wasn’t . . .

working

, was he? Why did Gus want someone else? Did he think she wasn’t doing a good enough job? Bee prodded the possum. Its fur was thick and stiff at the back, but it had a lovely soft fuzzy belly. Its blood, organs and bones had all been removed, leaving just skin and fur and claws and whiskers.

Bee glanced at the young man, who winked at her and grinned. Bee scowled and looked away. She and Gus had a

routine.

This new boy would ruin everything. She measured and snipped a piece of galvanised wire twice the length of the possum’s torso, and bent it into a possumish shape, referring to the page of

Anatomy of Australian Mammals

open beside the possum. She tugged a handful of cottonwool from a large bag under her desk, then wrapped it tightly around the wire frame, making it thicker in the middle and tapering it off at either end. She held it up next to the possum and squinted, checking the book again, and marked the position of the shoulders, hips and tail with a black texta.

Gus was making notes in the exhibition plan folder on his desk. The new boy was bent over the emu that Gus had been working on, carefully threading wire into its neck and packing it tightly with cottonwool. He looked up, as if he could feel Bee’s eyes on him. She quickly turned back to her possum. How come he got to work on the emu, instead of a boring old possum?

Bee had first visited the Museum of Natural History in Year Eight, on a science excursion. She’d loved its order and precision, and in Year Ten she’d returned to do her work-experience placement. Last year her science teacher had recommended her for an assistant job in the taxidermy department, and she’d started working with Gus after school and on weekends. She’d been there full time since school had finished in early December (with a week off for Christmas), and would stay until she started Year Twelve in February.

Bee loved working at the museum, so much that she didn’t mind the long hours and rather token salary. Initially she had just fetched and carried for Gus and watched him work. He’d barely spoken to her for the first few weeks, except to grumble about the ‘newfound nonsense’ practices of covering polyurethane moulds with animal skins – he insisted on nineteenth-century techniques involving cottonwool and wire.

But they had an

understanding

, a shared appreciation of order and methodical attention to detail. Every morning they would work in companionable silence until eleven, when Bee would go upstairs and order two triple espressos from the museum café. Sometimes she bought a lamington or a vanilla slice for herself, but Gus only ever had coffee.

After Bee had gained Gus’s trust (and, she hoped, a little of his grudging respect), he let her do bits and pieces of real work: finishing off a foot or a wing, or inserting a glass eye. The possum was her first solo project, and she thought it was turning out rather well.

The Department of Preparation was located underground, in the vaults of the Natural History Museum. These rooms were known as ‘the Catacombs’, and as well as the partially renovated taxidermy lab and the other preparatory studios, they comprised a rabbit warren of storerooms containing old display cases, disused stuffed animals, and lumps of rock that scientists of the early twentieth century had thought were meteorites, but had turned out to just be plain old rocks. The lab was always cool and quiet: a haven from the heat and bustle of summer, and the hot breath and sticky hands of the children who swarmed through the museum every day of the school holidays like grizzly, hyperactive locusts.

Best of all, Bee liked the laboratory because it was ordered. Neat and scientific. Each process straightforward and methodical. She was unperturbed by the animal carcasses – and their inevitable cycle of breakdown and decay. Death, after all, was a natural process. It was predictable, normal, everyday. Dead animals were far less mysterious than the messy unpredictability of living people. In the taxidermy lab, every mystery had an answer.

Mysteries had always been a big part of Bee’s life. When she was little, she had wanted as much mystery as the day could contain. She was forever tapping on the walls of her brick-veneer suburban home, hoping for a panel to swing out and reveal a secret passage. She kept a meticulous diary full of observations of everything around her – in code, of course – down to the postman’s arrival time, and the number of thick fantasy novels on her mother’s bedside table. She observed and analysed. One just never knew what would later reveal itself as a clue. Bee had insisted that her mother call her Trixie – after wholesome girl-sleuth Trixie Belden – and she had carried a detective kit everywhere she went, containing a magnifying glass, a pair of rubber gloves, a notebook, a sharpened pencil, a battered Miss Marple novel and a lipstick, because, as Nancy Drew had taught her, lipstick wasn’t just for glamour – it was also useful for writing SOS messages on windows and mirrors if one happened to find oneself locked in a room by a malicious and vengeful gardener, uncle or heir to a fortune.

But everyone had to grow up sooner or later, and by the time Bee was eleven, reality had sunk in. Real life bore no resemblance to Nancy Drew or Trixie Belden novels. It was more like Ian Rankin or Raymond Chandler. Bee may have had a short-fuse quick temper like Trixie Belden, but the resemblance ended there. She didn’t live in a sleepy town surrounded by beautiful autumnal woods and hidden caches full of jewels the way Trixie Belden did. And as for Nancy Drew, nobody could ever be as perfect as Nancy. She could paint, sew, cook and play bridge. She was fluent in French, and was a skilled dancer, musician and physician. And she could drive a motorboat or a car like a pro at the age of sixteen, not to mention fly a plane in heels, without messing up her hair. And all under the tender gazes of her rich, doting father and adoring boyfriend.

Bee frowned. What was Nancy’s boyfriend’s name? She could picture him in her head. He was tall and broad-shouldered and square-jawed and white-toothed. But what was his

name

?

‘Toby,’ said a voice in Bee’s ear. She turned to see the new boy bent over her desk, examining her work.

‘No,’ she said, shaking her head. ‘It wasn’t Toby. It was . . . Todd or Brad or Ken or something.’

‘What?’ He squinted at her through his glasses.

Bee assessed him with a practised detective’s eye. He was wearing an almost threadbare navy penguin polo shirt that looked to be from the eighties. Bee wondered if it was expensive-trendy-vintage-shop second-hand, or the more noble op-shop second-hand. Either way, it was an excellent fit, and showed off well-shaped arms and a chest that was solid without being ripped. The boy clearly exercised, but wasn’t a fitness junkie. Dumbbells at home, Bee guessed, and the occasional run. He almost certainly owned a bicycle.

The faint outline of stubble indicated that he shaved, and a red nick on the left side of his jaw suggested that he hadn’t been doing it for long. His skin was generally clear, his eyelashes were thick and his brows were well-shaped. He smelled clean, like soap and boy-deodorant. She couldn’t detect a tobacco odour on him, and although his cuticles and nails were disgracefully chewed, there was no evidence of nicotine staining.

He raised his eyebrows at her and Bee felt her face redden. He probably thought she was looking at him in an . . . appraising kind of way because she liked him. Not because she was a totally objective observer of human behaviours and characteristics.

‘Nothing,’ she said. ‘Are you here to work on the exhibition too?’

He nodded. ‘I’m a second-year med student,’ he said. ‘This is extra credit. You?’

Bee shrugged. ‘Just a summer job. I’m starting Year Twelve in a couple of weeks.’

He grinned in that patronising

good luck

way that uni students had. Bee observed that he had excellent teeth, and surmised that he’d probably had some serious orthodontic intervention.

Behind them, Gus cleared his throat. It was a husky, rattling sound, as if he were clearing cobwebs that had been there since his birth, which Bee assumed was a very long time ago, as Gus was at least seventy. ‘Those critters aren’t going to stuff themselves,’ he said, in his growly voice with the hint of an English accent.

The boy – Toby – rolled his eyes at Bee, and she smiled back, then immediately felt annoyed at herself. Gus’s slice of beetroot finally escaped the confines of his sandwich, and planted itself firmly on the front of his hoodie. He swore, then gingerly picked the beetroot up between thumb and forefinger and ate it.

At 10:53 am (or 10:50 by the lab’s clock), Bee climbed the stairs leading from the Catacombs and stood outside in the sun for five minutes, clearing her head of preservation chemicals and irritating thoughts about Toby. The shock of being in the beating heat of summer was pleasant for about three of those five minutes, until Bee’s jeans started to stick to her thighs. She pushed her sunglasses up her nose.

‘Hot,’ observed Toby, appearing beside her with a can of lemonade.

Bee had a personal policy of not replying to redundant statements, so she ignored him. She wondered absently what made him chew his cuticles so viciously. Anxiety? What did he have to be anxious about?

‘You haven’t told me your name,’ he said.

Bee told him, abruptly, and wondered if today would be a vanilla slice day or a lamington day.

‘That Gus is a bit of a character, hey?’

Bee sighed. Small talk was so mundane. She retreated into the blissful cool of the museum, and purchased two triple espressos from the café. She wasn’t going to let Toby ruin her routine.

She walked back the long way through the exhibitions hall, instead of along the concrete staff-access corridors. The older sections of the museum – the Mollusc Room, the Hall of Native Flora, the Geology Exhibit – were not as popular with the children, so it was a reasonably peaceful walk. Bee liked looking at all the creatures, frozen in time and space with the help of wire, cottonwool and lots of chemicals.

In the Weights and Measurements display, a ruby-throated hummingbird perched on one side of a tiny set of scales, balanced on the other by two paperclips. It was overshadowed by the hulking grey mass of an African elephant, balanced on a much larger set of scales opposite a pinkish-grey replica of a blue whale’s tongue.

As she passed the Red Rotunda, a small yet grand octagonal room painted in a rich vermilion, Bee heard voices and paused by the entrance. One of the tour guides was talking to an old man sitting in a straight-backed leather chair in the centre of the room.

‘I’m so sorry to interrupt you, sir,’ the tour guide said, sounding rather breathless. ‘But I heard you introduce yourself at the front desk and I just wanted to tell you that I am a huge fan. Your research is so inspiring; you’re a total hero in this place.’

Bee peered at the old man. He didn’t look like a hero. Deep wrinkles carved lines and fissures into his face. His chin bristled with stubble, and thick white hair curled around his ears. His eyes were the palest blue, like the colour of a cloudless sky nearest the horizon at dawn. They were also watery and red-rimmed, as if he’d been crying, although Bee supposed that it was just the effects of age. And yet he looked sad, sadder than Bee had ever seen anyone. Maybe he had been crying after all.

‘Dr Cranston?’ the tour guide said. ‘Are you okay?’

The man looked up, startled. It was as though he hadn’t noticed the tour guide until then. Bee guessed he was around seventy years old.