A Poisoned Season (36 page)

“No, I was perfectly safe. Inspector Manning was never far away.”

“It’s all so dreadful. Poor Isabelle. To know that her own mother is capable of such terrible things.”

“And all in the name of protecting her daughter,” I said. “It’s ghastly.”

“I do wish there was something we could do for her.”

“I’ve sent her a note this morning, but I don’t expect she’ll reply.” Poor Isabelle was in a precarious situation, but I understood completely that she would not want my help. All the papers would be full of the story of her mother’s downfall, and there could be little doubt what the outcome of her trial would be. I only hoped that, as she was a woman, Lady Elinor would be spared from execution. “I wonder if anyone’s sent for her brother?”

Inspector Manning called soon after Ivy left, and found me still at breakfast. He knew better this time than to resist my offers of food. He filled a plate and sat across from me.

“She’s made a full confession,” he said. “She believed your letter was indeed from Mrs. White. Gave Mrs. Brandon laudanum in an attempt to distract you, because she’d started to worry that you were

onto the scheme. I don’t think there was ever any intention of harming her.”

“So Stilleman’s death was an accident?” I asked.

“Yes. Lady Elinor only intended to kill Mr. Francis. Stilleman was allowed to take what he wanted from the toiletries in the dressing room, and made the bad choice of selecting the shaving lotion. Jane Stilleman was released from prison this morning. Would you like to go to Richmond and bring Mrs. Francis the news?”

“I would,” I said, and for a second time, left the inspector breakfasting at my table.

Beatrice wept when I told her the story. “I had no idea. No idea at all who he was.”

“I wish I could offer you some comfort.”

“Why didn’t he tell me?”

“I don’t know. To protect you, I suppose.”

“Foolish man!” Her handkerchief already soaked, I gave her mine, which she used to wipe the tears from her face.

“There is something else you must know,” I said. “Something that will be difficult to hear.” Beatrice took the news of her husband’s illegitimate son better than I would have expected. She cried, but softly, no gasping sobs.

“Is there any point to being angry with him now?” she asked. “That child is all that is left of him. Can I regret what he did? He so desperately wanted a son.”

I left her but, instead of going home, went to Mr. Barber’s studio to ask him to go to Richmond at once. He would be more capable than anyone of offering comfort to Beatrice.

W

ithin a few days, Monsieur Garnier’s coup had been abandoned. Word that Charles Berry was a fraud scandalized his supporters,

and Garnier was too savvy a politician to ally himself with such a man. Cécile was disappointed never to have had the chance to lure Garnier away from his plans but remained convinced that she, like Boulanger’s mistress before, would have been more attractive to a man than the idea of ruling a nation.

As for Mr. Berry, he disappeared from Paris as soon as the news broke that David Francis was the true heir of the dauphin. Although we were not able to keep from the press the news that Francis had a son, we did manage to persuade them not to identify the boy. It was rumored that Berry had returned to America, and I hoped that to be true, preferring to have the vile man as far from me as possible. I’d written Colin to inquire about the list of stolen objects I’d found in the Savoy; he believed that Berry kept it because he planned to ask that everything belonging to the queen be given to him once he was named king of France.

Once the case was fully settled, I began to make plans to travel to Santorini. I was eager to see Mrs. White and relieved that I would not have to tell her that Lady Elinor had burnt down her house. Meg’s absence meant that I had to rely on another maid to pack for me, and she required more direction than I was used to having to give. I had just sent her back upstairs after her third trip to the library to inquire about the specifics of what I would need when my mother burst through the door, Davis close on her heels.

“Lady Bromley to see you, madam,” he called out over my mother’s shoulder.

“Again you have embroiled yourself in controversy,” she said. “I am most displeased. The newspapers are full of the role you had in bringing down Lady Elinor. It is disgraceful, unladylike, outrageous.”

“Mother—”

“It is of no consequence, however. I am here on the queen’s business. She asked that I inquire whether you had yet made a decision about the matter we discussed with her at Windsor.”

“A decision?” I asked.

“Don’t play dumb with me, child. You know perfectly well that Her Majesty expects you to marry. Who is the lucky gentleman to be?”

“Colin isn’t even in England.”

“Then Bainbridge. Excellent. I do like the idea of your being a duchess. And I heard all about the falling-out he and your American friend had.” Margaret had expertly staged the event. She cried, he stormed off, and somehow everyone felt sorry for her before the end of the evening. Even the lord mayor of London himself consoled her. Her parents felt particularly bad and were convinced she had been ill used and was heartily disappointed. So convinced, in fact, that they agreed to let her take up residence in Oxford a full three weeks before they’d intended. Her only disappointment, she insisted to me, was that she hadn’t been there to confront Lady Elinor with me. That, she said, would have made her Season complete.

“Jeremy hasn’t proposed to me, Mother.” I shook my head. “Haven’t we already had this conversation?”

“Let me assure you, Emily, that it is a conversation that will be repeated at regular intervals until you have an answer for the queen.”

“Perhaps when I return from Greece—”

“Greece? Good heavens, you can’t intend to go back there! What will you do? Mr. Hargreaves isn’t there, is he? It wouldn’t be proper without a chaperone, although if you were engaged…”

I let her prattle on and gave her very little trouble. I felt I owed it to her after all she’d done to save my reputation. I listened to her well enough only to know when to give the right meaningless answers and wondered what she would do with herself if ever I did remarry. Hound me for an heir, I suppose. I shuddered at the thought.

W

ith Lady Elinor in prison, I’d been able to persuade Colin that my house no longer needed to be guarded. I insisted that Se

bastian, should he ever come back, would not harm me. On my last night in London, I awoke to find that, once again, an intruder had come into my bedroom. This occasion, however, brought me no fear. Sebastian had been perfectly quiet, disturbed no one in the house, and had not had to cut through my window; I’d left it open, an invitation of sorts, I suppose, though not one I had consciously made. On the pillow next to me, I found a bundle of letters, a rose, and a small box. An oddly familiar scene.

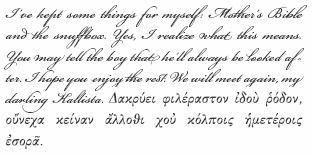

I opened the letters first. One was from him; the other two were those that Lizzie had stolen from my library. His note was, as always, short:

I could read the Greek with little difficulty:

Lo, the lovers’ rose sheds tears to see her away, and not on my bosom.

It came as no surprise to find that the box contained Cécile’s Marie Antoinette earrings.

I

WAS IN

G

REECE BY THE END OF THE FOLLOWING WEEK, HAVING TRAVELED

through Paris to give Cécile her earrings and to collect her, Caesar, and Brutus. I wanted her in Greece with me and knew that I could not have her without her dogs. Colin was no longer in France, having been summoned by Buckingham Palace to Vienna to work on I knew not what. I missed him but was content to be back on Santorini, basking in the warm sun, unable to get enough of the salty air.

Mrs. White had been quite altered by her stay at the villa; I hardly recognized her when I arrived. Mrs. Katevatis, my cook, had been horrified when she first saw the woman and immediately took her under wing. She fed her all the wonderful Greek food I had come to love, and before long Mrs. White had started to gain weight and eventually lost altogether the gaunt, pained expression that I had seen when I first met her. Edward thrived on the island, chasing Cécile’s dogs and following Adelphos, Mrs. Katevatis’s son, everywhere. Edward idolized the older boy. The trip had done both mother and son immeasurable good.

I let Mrs. White explain to the child who his father had been, and after she had finished, I presented him with a gift from Beatrice:

Marie Antoinette’s pink diamond. He was too young to understand the significance of the stone and its history, but someday he would, and I hoped it would bring him some measure of happiness.

We fell into a happy routine at the villa, and as always when I was in Greece, I thought that I should never want to leave. Cécile and Mr. Papadakos, the village woodworker, had completed the miniature rendering of Pericles’ Athens they had started on in the spring and were now working on a re-creation of the temple of Artemis at Ephesus. I studied my Greek, dividing my time between reading Homer and practicing the modern language by conversing with the villagers.

We ate breakfast outside whenever the weather was fine, and on this day the sky was bluer than ever, and the Aegean Sea spread below us like a great swathe of sapphire silk. I was reading the mail and nearly jumped out of my seat when I opened the first letter in the pile.

“I cannot believe it!”

“What is it?” Cécile asked.

“Mr. Bingham has donated the silver libation bowl to the British Museum.”

“I am most impressed. You have mastered the art of persuasion.”

“Don’t get too excited. He says that he did it only because he could no longer stand being bothered by me with such astounding regularity. Excellent phrase, don’t you think? Astounding regularity. ‘It is as if, Lady Ashton, you are the tide, banging away at a delicate seashore, oblivious to the effect of your battery on the sand.’” I laughed. “I’d far prefer to be the ocean than the sand.”

“Kallista, you have a visitor,” Mrs. Katevatis called to me from the kitchen window. “He’s said he would wait for you on the cliff path.”

Now I did jump from my seat, knowing instantly that there was only one gentleman who would come all the way to Imerovigli to call on me. The village, perched high atop a cliff on the island, was connected to the city of Thíra by a path that offered spectacular views. I walked along it nearly every day, and it was here, months ago, that

Colin had proposed to me. Today when I found him, he was looking over the caldera at the remains of the ancient volcano, but he turned to face me as soon as he heard me approaching.

“I have to admit that, in the end, you did win our bet,” Colin said, taking my hands. “So I’ve come to Greece as you demanded.”

“Here only out of duty?” I asked, smiling, wondering how I could have forgot how perfectly handsome he was.

“There are some duties a gentleman prefers to others.”

“How was Vienna?”

“I’ve actually come from London. I had some business there.”

“Anything that would interest me?” I asked, fully expecting his usual reply to this question.

“Yes, actually. I hope it will all interest you. But first, I’ve some gossip I think you’ll be pleased to hear.”

“What?”

“Lord Pembroke has caused a scandal that has shaken the aristocracy to its core.”

“Dare I even hope? What did he do?”

“He eloped to Gretna Green with Isabelle Routledge.”

“He didn’t!”

“He did.”

“That is most welcome news,” I said. “My faith in the English gentleman is restored.”

“I’m glad to hear it. Now for the rest.” He pulled some papers out of the pocket of his white flannel jacket. “Your solicitor sent this. It’s a list of houses he thinks might suit you in London.”

“Oh.” I took the paper from him and glanced at it, hating the thought of having to set up an entire house, dreading the emptiness of it, and feeling a piercing disappointment that such impersonal business had brought him to me.

“Anne confirmed that there is no need for you to feel that you can’t stay at Berkeley Square.”

“That’s kind of her.”

“I hope that the rest of these will change your mind about purchasing a house altogether. I cannot leave my estate to you, Emily, and I am aware of the difficult position in which that could place you. I can’t break the entail, but I can do this.” He handed me two pieces of paper.

I gasped as I looked at the one on top. “A deed for the books in your library?”

“All of them. They’re yours, whether you marry me or not. I’ve settled them irrevocably on you.”

The next paper made me laugh out loud. “Your port? You’re giving me all of your port?”

“I do hope you won’t object to my keeping the whiskey.” Our eyes met, and I thought I could stand there forever drinking in his love for me. He brought his hand to my cheek, gently, barely touching it, but the sensation was completely overwhelming; it had been so long that I could hardly remember the feeling of his skin on mine.