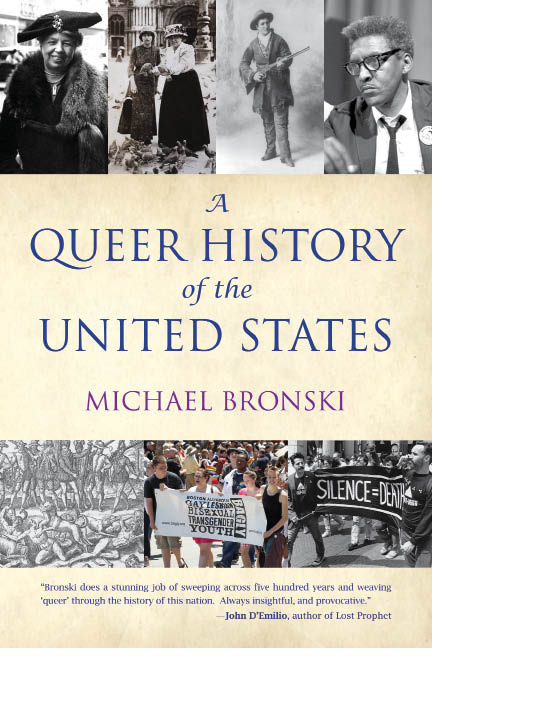

A Queer History of the United States

Read A Queer History of the United States Online

Authors: Michael Bronski

Tags: #General, #History, #Social Science, #Sociology, #United States, #Lesbian Studies, #Gay Studies

Other Books by Michael Bronski

Pulp Friction: Uncovering the Golden Age of Gay Male Pulps,

2003

The Pleasure Principle: Sex, Backlash, and the Struggle for Gay Freedom,

1998

Taking Liberties: Gay Men’s Essays on Politics, Culture & Sex

(editor), 1996

Flashpoint: Gay Male Sexual Writing

(editor), 1996

Culture Clash: The Making of Gay Sensibility,

1984

Other Series Published by Beacon Press

Queer Action Series

Come Out and Win: Organizing Yourself,

Your Community, and Your World,

by Sue Hyde

Out Law: What LGBT Youth

Should Know about Their Legal Rights,

by Lisa Keen

Queer Ideas Series

Beyond (Straight and Gay) Marriage:

Valuing All Families under the Law,

by Nancy D. Polikoff

From the Closet to the Courtroom:

Five LGBT Rights Lawsuits That Have Changed Our Nation,

by Carlos A. Ball

Queer (In)Justice:

The Criminalization of LGBT People in the United States,

by Joey L. Mogul, Andrea J. Ritchie, and Kay Whitlock

A Queer History of the United States

Michael Bronski

ReVisioning American History

Beacon Press   Boston

Dedicated to

Carl Wittman (1943â1986)

John Mitzel

Charley Shively

comrades, all

and

John Bronski

my father

Author’s Note

A Queer History of the United States

is the first book in Beacon Press’s ReVisioning American History series. This series is committed to offering fresh perspectives and examining our history through the lens of those groups whose stories have been excluded from the canon.

I am a cultural critic, independent scholar, progressive activist, and college professor who has written for four decades on a broad range of topics concerning lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender culture. This book makes a series of observations and arguments concerning how to think about the place of LGBT people in U.S. history. It looks at how American culture has shaped the LGBT, or queer, experience, while also arguing that queer people not only shaped but were pivotal in creating our country.

Readers may not find names and events they expected and may be surprised to find little-known names and historical connections. This is not a comprehensive history, so I have been judicious about what I have chosen to include. It is foolish to think that there can be an objective view of history. Every writer approaches the “facts” with her or his own experiences, views, and biases. Like Howard Zinn’s

A People’s History of the United States—

a book that inspired me, but was not the inspiration for this book—

A Queer History of the United States

has a political point of view. I hope that point of view serves as a guide to help the reader make sense of the materials presented, but also makes my own biases clear enough so that my interpretations can be resisted.

My earliest involvement in the gay community was in the gay liberation movement of the early 1970s. We had very strong opinions then. I have come to realize that in life and politics, there is always more to take into consideration. If there is one clear, unambiguous argument here, it is that the LGBT history of America is, and has always been, U.S. history.

Michael Bronski

Introduction

A decade ago, when I first began teaching lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender studies at Dartmouth College, I was invited to a fraternity house to moderate a group discussion titled “Don't Yell Fag from the Porch.” The frat was renowned for its rowdiness, and indeed, someone had recently yelled “faggot” at a student passing byâundoubtedly not for the first time. After being publicly challenged on this behavior, the frat brothers decided to host a public forum on homophobia in the Greek system. The discussion went well and became an annual event. “Faggot” was yelled with less frequency, and in a few years the fraternity even had a few “out” gay members. But that evening, and over the years, what bothered me was that the entire discussion was predicated on the idea that Dartmouth College was essentially a straight place that had to be open to “gay people.” But that makes no sense. We all know that lifeâand historyâis far more complex than that. Or do we?

All too often most of us think in terms of simple dichotomies, including gay and straight; but who might answer to the call of “fag” when its history has been shown to be more than a simple either/or question? Here are a few lines from a letter Daniel Webster, a Dartmouth alumnus and hero to the college, wrote in 1804 at the age of twenty-two to the twenty-three-year-old James Hervey Bingham, his intimate from their college days: “I don't see how I can live any longer without having a friend near me, I mean a male friend. Yes, James, I must come; we will yoke together again; your little bed is just wide enough.” Was Daniel Webster gay? Did he love James? Did they have a sexual relationship? If so, what did this mean for his two marriages later in life? Is this queer history?

The last ten years of teaching LGBT studies has for me been a continual process of trying to figure out what is LGBT history. How do we understand it? How do we use it to think about the past? How do we use it to think about the present and the future? I certainly would have liked to quote Webster's words while moderating “Don't Yell Fag from the Porch.” What would the students have thought about Webster's obsessive desire to lie in bed with his friend James once again and hold him fast to his body? Or what if I had told them that poet Richard Hovey, who wrote the lyrics to the school's “Alma Mater,” was also a lover of men, and although married and an ardent feminist, socialized in gay male circles in America and Europe? (Oscar Wilde once famously hit on him at a party.) Would it have been another reason for their not shouting “faggot” as frequently? Would this have “queered” Dartmouth for them? One of the reasons for titling this book

A Queer History of the United States

is an attempt to “queer” how we think about American history.

The questions of this book are much larger than who might have been “gay” in the past or had sexual relations with their own sex. Over the past forty years a great deal of incredible scholarship on LGBT history has been written, and I have drawn extensively upon it, rethought it, and synthesized it here. What follows is a long meditation on not only LGBT history but, because it is inseparable, all of American history. After two years of thinking and writing, I want to start by suggesting that there are two crucial concepts to consider when examining LGBT history in the United States.

The first is that the contributions of people whom we may now identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender are integral and central to how we conceptualize our national history. Without the work of social activists, thinkers, writers, and artists such as We'Wha, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, Martha “Calamity” Jane Cannary Burke, Edith Guerrier, Countee Cullen, Ethel Waters, Bayard Rustin, Roy Cohn, Robert Mapplethorpe, Cherrie Moraga, and Lily Tomlin, we would not have the country that we have today. Women and men who experienced and expressed sexual desires for their own sex and those who did not conform to conventional gender expectations have always been present, in both the everyday and the imaginative life of our country. They have profoundly helped shape it, and it is inconceivable, and ahistorical, to conceptualize our traditions and history without them.

The second, and slightly counterintuitive, key concept is that LGBT history does not exist. By singling out LGBT people and their lives, we are depriving them of their centrality in the broader sweep and breadth of American history. The impulse to focus on lives that have been shunned, marginalized, censored, ignored, and hidden in the pastâand in previous histories of the United Statesâhas been revolutionary in the growth of a vibrant LGBT community. This impulse is part of a larger social and political movement of Native American, African American, Latino/Latina, and other marginalized identities and cultures to reclaim and celebrate our “lost” histories. (Although as an identity, LGBT has, as we will see, a much newer history than other identities.) But it is equally important to understand that this is a transitional moment in history that has emerged in the past forty years precisely because those marginalized groups were so deeply dismissed.

If LGBT history resides in the queer space of being both enormously vital and nonexistent, can we even write and speak about it? How do we uncover and explicate the past so that it brings new understandings to popular culture and scholarly pursuits alike? How will this history resonate with our understanding of our own contemporary and historic lives?

We have been taught, in our nation's fairly unimaginative educational system, that history is a stable linear narrative with a fixed set of factsânames, dates, political actions, political ideas, laws passed and repealed. In

The Dialectic of Sex,

a groundbreaking book of radical feminist theory, Shulamith Firestone writes that this conventional way of understanding the historical process as a series of snapshotsâhere is the American Revolution, here is the Declaration of Independence, here is the Emancipation Proclamationâis limiting and ultimately unhelpful. History, she states (drawing loosely on Marxist theory), is “the world as process, a natural flux of action and reaction, of opposites yet inseparable and interpenetrating . . . history as movie rather than as snapshot.”

Much of the popular LGBT history that has been published in our newspapers, magazines, and blogs falls into the category that Firestone criticizes. It is essentially a list of famous lesbian or gay people and events used to justify contemporary understandingsâhere is Oscar Wilde, here are the Stonewall Riots, here are queer couples being married in Boston. This family album approach is appealing, because it provides a sense of identity and history, but it is ultimately misleading. In past decades women's and gender studies scholars called this method of analysis “add one woman and stir.” The “important” women were added to the mix to create a gender balance, but there were no new layers of complexity or nuance as to what these women's lives, thoughts, desires, and actions might actually mean for a shared historical past.

More serious writing on LGBT history has avoided this approach. Historians such as Jonathan Ned Katz, Lillian Faderman, Allan Bérubé, George Chauncey, and Esther Newton, among many others, have examined how LGBT history complicates and enriches the American imagination and the national story we already know. I have drawn extensively on these writers, and many other sources, to present a daringly complex vision of the past, one that forces a fundamental rethinking of what we thought we knew, as well as of the present and even the future. Its broad use of facts, historic personalities, and events is an invitation to join in a larger intellectual project of reinterpretation. As Firestone argues, history is a movieânot a Hollywood film with a traditional narrative, but rather an experimental film that presents a reality that makes sense only when we appreciate its intrinsic narrative complexity. History is an ongoing process through which we understand and define ourselves and our lives.

Language and Identity

We cannot understand history or know what it means to us today without first understanding the process by which it is written. The writing and reading of history is always, consciously or not, a political act of interpretation. The political, intellectual, and social conditions of a particular time period affect who is writing, what they are writing, and why they are writing. The writer must construct a narrative that makes sense for her or his present social and cultural context, as well as contextualize that narrative in a broader historical framework. This process depends on the availability of both historical facts and language that can convey a clear, precise understanding of the facts and their context.

While the contemporary project of writing LGBT history began in earnest during the gay liberation movement of the early 1970s, previous writers penned what might be seen as early attempts to construct histories of people with same-sex desires. Plato's mythical analysis, in his

Symposium

,

of why some people were sexually attracted to their own sex had an enormous effect on how other writers in the Western tradition conceptualized same-sex desire. Some historians of the classical periodâPlutarch in his

Lives

and Suetonius in

The Twelve Caesars

, for exampleâwere interested in chronicling the same-sex desires of notable men. Vasari, in his 1550

Lives of the Painters

, hints at the same-sex desires of Michelangelo and other Renaissance artists. While these works did not focus strictly on homosexual activity, they did not avoid or hide it. In the mid to late nineteenth century, two social and legal reformersâKarl-Maria Kertbeny, an Austrian-born Hungarian, and Karl Ulrichs of Germanyâseparately wrote articles, pamphlets, and books about same-sex behavior, as did John Addington Symonds, an English art historian. All three drew upon notable figures of antiquity and the Italian Renaissance to prove that there was a centuries-old tradition of same-sex behaviors. Their works sought to make a case for both the naturalness of same-sex desire and the reformation of laws that criminalized homosexual behavior.

These works are clearly contextualized by their times. Plutarch and Suetonius present the little data they haveâsome of it gossipânonjudgmentally. While not particularly naming same-sex activity, they describe it as a facet of human activity. This is also true of Vasari, but he is more coded, since by the Renaissance homosexual activity was branded a grave sin and a serious crime by the Roman Catholic Church. These writers were also limited by writing about people and events very close to their own times. This type of historical projectâlike writing about a recent presidential administrationâhas clear boundaries for access to materials. Kertbeny, Ulrichs, and Symonds took a different approach. They cautiously, but quite consciously, drew upon a far wider range of materials, including recent historical research, advances in archaeology, and scholarly reconstructions of past literatures. Their class and educational backgrounds gave them the necessary social and political access to write and disseminate their ideas.

Each of these historical works is as much a portrait of the time in which it was written as it is a narrative of the past. Each was written to make emotional and psychological sense to its contemporary readers. Plutarch and Suetonius were interested in exposing the political and psychological foibles of their subjects. Varsari was trying to “explain” as best he could the social and emotional relationship of Renaissance artists to their audience and to a hierarchy of patronage that funded and controlled their work. While these three writers had definite points of viewâwe could fairly call them political and social “agendas”âKertbeny, Ulrichs, and Symonds were making a clear, unequivocal case for the cultural and legal acceptance of same-sex desire and activity. Post-Enlightenment German and British cultures were progressive enough to allow such ideas to circulate, albeit in a limited sphere.

Existing terminology, like the larger cultural context, limits the scope of what writers are able to say. Religious terms that described same-sex activity as sinful, such as “sodomite,” were in common use in Europe and England from the late thirteenth century. Sexual offenses, especially homosexual behavior, were often referred to in canon law and civil codes with the elliptical terms “crimes against nature” or “the unmentionable vice,” thus emphasizing that such actions were so aberrant as to be literally unspeakable. Beginning in the late sixteenth century, the term “catamite”âa corruption of Ganymead, the boy lover and cup bearer for Zeus in Greek mythologyâwas used, usually negatively, to describe men who had sex with men. In eighteenth-century Great Britain, “molly” was used so frequently to describe men, often gender deviant, who desired other men that the private homes or tavern rooms in which they congregated were called Molly Houses.

The rise of capitalism in Europe and the strong influence of individuality within post-Reformation Protestantism gave rise to a new cultural notion: self-identity that was specific to an individual but associated with a larger group. Ulrichs began using “urning,” a term he borrowed from Plato's

Symposium,

as well as “invert,” which connoted a person who possessed the soul of the other sex, to refer to people who experienced same-sex attraction in a nonjudgmental way. Kertbeny invented the word “homosexual” in 1869 to help him construct a narrative around a person defined by his or her same-sex sexual desires and actions. Beginning in the late nineteenth century in Europe and Great Britain, “sapphist,” from the Greek poet Sappho, was used occasionally to describe women who loved women, and the practice was referred to as “sapphism.” The word “lesbian,” referring to the Isle of Lesbos, the home of Sappho, was first used by sexologist Havelock Ellis in 1897. Until fifty years ago, it was common for lay people, journalists, and social scientists to use “invert” along with “homosexual.”