A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy (11 page)

Read A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy Online

Authors: Thomas J. Cutler

The actions of the Sailors in those hopelessly outclassed destroyers are among the most courageous acts in the whole of the U.S. Navy's history. Together, as crews, they accomplished the seemingly impossible. As individuals, they leave us images that most of us can barely imagine, much less firmly comprehend: Paul Henry Carr with his body mortally wounded, holding up the last projectile to be fired; laundryman Bill Mercer running onto the exposed forecastle to clear away empty shell casings; Jackson McKaskill enduring terrible burns to secure steam valves; Ernest Evans refusing treatment for his wounds as time and again he took his ship into harm's way; the hundreds of Sailors who carried out a thousand duties while their ships were being torn apart around them. This is courage of the highest order and is fitting to the high ideals of a great nation.

When they rolled Chief Boatswain's Mate Carl Brashear into the emergency room at Torrejon Air Force Base in Spain, he had no discernible pulse and barely the faintest of heartbeats. He had lost massive amounts of blood despite the two tourniquets that had been applied to his leg, and when the bandages that had been applied at the scene of the accident were removed, his foot fell off.

Eighteen pints of blood later, Brashear began to come back from the threshold of death. For most people, surviving would have been enough. But Carl Brashear had just begun to fight.

Hours before, Chief Brashear had been the picture of health. A Navy diver, he was among the most physically fit people in the world. It was March 1966, and Brashear and his shipmates were diving off the coast of Spain, trying to locate a nuclear bomb that had been lost at sea when two U.S. Air Force planes suffered a midair collision. It was a mission of vital importance, and Brashear and the other divers had been diving around the clock for two months, investigating every possible sonar contact that might prove to be the lost weapon.

When they at last located the bomb, a salvage operation began, and Brashear was in the thick of it. After the weapon was brought to the surface from 2,600 feet of water, Brashear was supervising the final operation of getting it aboard when a line parted. Every experienced Sailor knows that a parting line can be as lethal as a bullet, and Chief Brashear grabbed a nearby Sailor to yank him out of the deadly path of the whipping line. At that same moment, a pipe to which another line had been secured tore loose and flew across the deck, striking Brashear in the leg.

First aid was immediately administered, but it was clear that Brashear was in very bad shape. He was bleeding profusely, and his muscle-bound leg would not accept tourniquets well. The small salvage vessel was not equipped to handle an accident of this severity, so the mangled boatswain's mate was evacuated to the hospital in Torrejon.

Despite the best efforts of the hospital personnel, infection and then gangrene set in. Brashear was flown to a hospital in the United States, but things did not improve much, and doctors decided that amputation was the prudent answer.

Chief Brashear lost his leg. To all around him, and to the Bureau of Naval Personnel, it was apparent that this Sailor's career was over; he would have to retire on disability.

But Carl Brashear had other ideas. He was no stranger to challengesâas an African-American in a nation still adjusting to full integration and equal rights, he had overcome numerous obstacles to achieve what he had. He made up his mind not only to stay in the Navy but also to continue serving as a deep-sea diver.

He began reading about other people who continued to do amazing things after losing limbs. He studied how prostheses worked. As he recovered his strength, it soon became obvious to the hospital personnel that they had no ordinary case on their hands. Before his doctors thought it prudent, Brashear was working out to stay in shape. One session was so rigorous, in

fact, he broke off the temporary cast that had been rigged to shrink the stump of his leg. He refused to use crutches and worked around the hospital, doing chores to help out and prove that he was capable. A few people began to wonder if maybe, just maybe, this crazy man was going to achieve the comeback he kept promising. But convincing hospital personnel and convincing a Navy medical board were two different things, and Chief Brashear knew it.

Through his persistence, he managed to get himself transferred to Portsmouth Naval Hospital so he could be nearer to the diving school there in Virginia. At the first opportunity, he went to the school and told the officer in charge, Chief Warrant Officer Clair Axtell, that he wanted to dive. He also wanted to get some photographs taken to prove that he could do it. Axtell knew that if anything went wrong, it would be the end of his own career. But there was no getting around the look of determination in Brashear's eyes, and Axtell decided that, if this man had the courage to fight these tremendous odds, he would have the courage to risk his career.

Soon the one-legged man was diving in a deep-sea rig. Then in a shallow-water rig. Then in scuba gear. All the while, he had an underwater photographer snapping pictures as proof, which he then sent to the Bureau of Medicine along with the paperwork for his medical board.

Carl Brashear eventually convinced the Navy to give him the chance to prove himself. A captain and a commander were assigned to dive with and observe him in underwater action during a number of arduous tests, and every morning they watched as he ran around the building and then led the other divers in calisthenics.

The day finally came that decided Brashear's future. He appeared before a medical board tasked with deciding what to do with this man who had fewer limbs than the average, but who had mountains more courage and determination. The captain heading the board began with this observation: “Most of the people in your position want to get a medical disability, to get out of the Navy, and do the least they can and draw as much pay as they can. But then you're asking for full duty!” He then asked, “Suppose you were diving and tore your leg off?”

Chief Brashear smiled and said, “Well, Captain, it wouldn't bleed.”

The Navy relented in the face of Brashear's courageous determination. He was sent to the Navy Diver School for a yearlong trial under the tutelage and watchful eye of Chief Warrant Officer Raymond Duell. Cutting Brashear no slack, Duell had the amputee diver go down every single day that year. At the end of the trial, Duell wrote a powerfully convincing letter recommending that Brashear be restored to full diving status and duty. By now the answer was obvious. For the first time in history the Navy had a one-legged diver.

Brashear not only made history as the Navy's only master diver missing a leg, but he also became Master Diver of the Navy in 1975, the only black man to date to hold that position.

In 2000, Twentieth Century Fox made an inspiring movie about Carl Brashear called

Men of Honor.

Cuba Gooding Jr. played Brashear and Robert De Niro played a composite character named Billy Sunday, who represented the men like Axtell and Duell who had helped Brashear achieve his goal. Gooding told reporters what it was like to wear a 220-pound diving rig and simulate the action of a Navy diver during the filming of the movie: “At the end of the day I would sit on my steps in the trailer. I couldn't even walk into my trailer; that's how fatigued I was. I would rest my elbows on my knees and my whole body would start to shake, so I would have to sit up. It was a very strenuous movie.” Describing the man he was portraying, Gooding said Brashear is a man who “took everything seriously but not personally.”

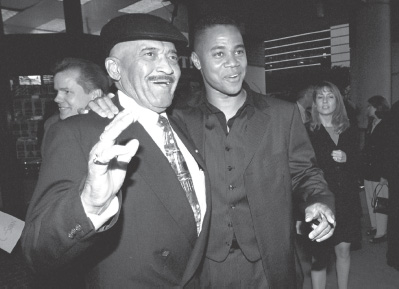

Retired Sailor Carl Brashear and actor Cuba Gooding Jr. together at a preview of the movie

Men of Honor.

Gooding played Brashear in the 2000 film based on the master chief's inspirational commitment to service.

U.S. Navy (Dolores L. Parlato)

Years after Master Chief Carl Brashear's retirement from the Navy, he told his story to the Naval Institute's historian, Paul Stillwell. When asked about that trial year, Brashear confided that because he was a chief, he led the diving school students in calisthenics each morning and “sometimes I would come back from a run, and my artificial leg would have a puddle of blood from my stump.” Fearing that a trip to sick bay might cause him to fail the trial, he would just “go somewhere and hide and soak my leg in a bucket of salt waterâan old remedy.” Matter-of-factly he added, “Then I'd get up the next morning and run.”

Courage comes in many forms.

The form of courage we most often think of and frequently celebrate is

physical

courage, as exhibited by the Sailors of Taffy 3 and Medal of Honor recipient James Elliott Williams. It is in our nature to admire such deeds. And well we should. Less often, however, do we recognize

moral

courage, the kind that does not risk one's body but does risk other aspects of one's life.

People sometimes face decisions that will affect their lives in some significant way. It may be as relatively small a thing as giving up a much-wanted leave period to help a shipmate in need, or it may be as significant as risking a promotion or even an entire career.

I have personally witnessed acts of physical courage that I will never forget, but I have also seen many more acts of moral courage during my years in the Navy. For example, there was the young petty officer who came to Vietnam late in the war, newly married and consequently terribly homesick. By chance, he happened to be in the personnel office in Saigon when a personnel drawdown was implemented; the officer in charge offered him the chance to go home after just a few days in-country. I could see in his eyes that he desperately wanted to say yes. But after a moment's hesitation, he answered: “No, there are others who have been here much longer. Let one of them go.”

There was the chief on a cruiser who was being pressured by his department head to find ways to spend leftover budget money at the end of the fiscal year “so they don't take it away from us next year.” The chief, who was eligible for promotion to senior chief that year, told the officer he could not spend the taxpayers' money that way.

There was the captain of an aircraft carrier who was facing an operational readiness evaluation that would determine the ship's deployability and thus affect the captain's chances of being selected for admiral the next

year. The night before the big evaluation was to begin, his battle stations officer of the deckâwho had been training in that slot for monthsâreceived a telegram that his wife's father had passed away. That captain must have been tempted to keep the man on board for obvious reasons, but instead he insisted that the man be flown off at first light so that he could be with his grieving wife in her time of need.

These are acts of moral courage, not risking life or limb but sacrificing or risking personal needs and wants. They occur far more often than do the death-defying feats we celebrate, and they sometimes have serious consequences, yet they are rarely recognized. Unlike acts of physical courage, which often occur spontaneously, acts of moral courage are often reached after careful deliberation, when rationalization is a ready ally.

Although we will probably never find a way to give full recognition to these acts, it is vitally important that we recognize they do happen and they are just as important as the inspiring acts of physical courage we rightfully admire.

When young Americans append the letters USN or USNR to their names, they accept the responsibility of defending a nation; of following in the footsteps of Boatswain's Mate Williams, Commander Evans, and Master Chief Brashear; of finding within themselves the physical and moral courage that are among the necessary tools of a Sailor. This is no small challenge to be sure, but history has proved that we need not worry. As each new day dawns, we can rest assured that the nation is in good hands, that courageâalong with honor and commitmentâis alive and well, and that the U.S. Navy will continue to do its job in the tradition set by ordinary people who have left us an extraordinary legacy.

| Commitment | 3 |

While a sense of honor is a prerequisite to military service, and it takes courage to face the dangers of the sea and the violence of the enemy, it takes a special kind of commitment to be a Sailor in the United States Navy.

Â

Among the many things that have always made Sailors different from other people is the way they live and work. There is some truth in the popular image of Sailors visiting beautiful and exotic places and enjoying the comforts of hot meals and a warm bed while their Soldier counterparts are eating cold rations and sleeping on the ground. There is another side of life in the Navy, however, that is often challenging, sometimes difficult to bear, and yet a source of great pride.