A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy (39 page)

Read A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy Online

Authors: Thomas J. Cutler

There is nothing new here. Far from it. Among the most prevalent legends of the sea is the idea of a jinxed or cursed ship, a vessel that is destined for bad luck, either by chance or from some supernatural cause. Tales from the biblical story of Jonah to Samuel Taylor Coleridge's classic poem “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” reinforce the idea in our culture. Some Sailors of the day tried to explain the disappearance of

Cyclops

as the inevitable outcome for a “jinxed ship,” pointing out that the ship had experienced other problems, including an accident in which a Sailor had been killed by the ship's propellers. More modern Sailors point to an imagined Kennedy-family jinx as the cause behind the

Kennedy-Belknap

collision.

In fact, seasoned Sailors know better. They know that jinxes can be explained in two ways. First is the luck factor. One does not have to be very old and wise to realize that life is not always fair and equitable. As the saying goes, “Bad things happen to good people”; likewise, bad things can happen to good ships. Despite her great reputation, USS

Watertight

might be caught in an unpredicted storm and lose her search radar antennaâeven though the shipyard did a flawless job of installing it and the ship's electronics technicians were meticulous about maintaining it.

Bad things also can happen to “bad” ships. The other factor that contributes to the jinx idea is almost as difficult to measure or quantify in any scientific way, yet “salty” Sailors will swear by it. The “personality factor” of ships has much to do with how they are perceived by others and something to do with how much good or bad “luck” comes their way. Any experienced teacher will insist that different classes have different “personalities.” “My

ten o'clock class is reserved and studious, while the one at eleven-thirty has more discipline problems but is also livelier during class discussions.”

Just as classrooms full of students take on composite personalities, so do ships. The word on the waterfront might be that USS

Watertight

is a “cando” ship, always ready to carry out any assigned mission speedily and efficiently, while USS

Neversink

is always a “little behind the power curve.” These “personalities”âactually reflections of leadership, morale, and other factorsâhave a lot more to do with what happens to a ship than does anything supernatural.

Neversink

is more likely to run aground or lose a man overboard than is

Watertight

because the latter is better run, with a well-trained crew and better leaders who keep morale high.

While jinxes are no more real than are bogeymen and hobgoblins, there is something in our nature that makes the possibility of such things attractive. Most likely it is the need for explanations and order. There is something more satisfying in knowing there is a reasonâhowever unscientificâfor an occurrence or series of occurrences than in having to accept that it is just random, meaningless coincidence, beyond any laws or control.

As long as strange but true things continue to occur, however, there will be legends and myths, whispers of jinxes, and tales of the supernatural. In truth, it is not altogether surprising in light of one final factor. Anyone who has been to sea and peered into its mysterious depths cannot help but wonder what lies below. Any Sailor who has watched the changing moods of the sea, or seen the dancing stars of luminescence in a ship's wake, or heard the ominous wail of the wind in a squall, will be tempted to think of powers beyond those of simple physics. The Sailor's realm is a hauntingly beautiful and sometimes ominous place to live and work and dream and wonder.

| Lucky Bag | 10 |

Maintaining good order, discipline, and cleanliness aboard ship has been a high priority in the U.S. Navy from its earliest days. One method for achieving these things was the tradition of the “lucky bag.” As the tradition goes, any personal items left out in the berthing compartment (“gear adrift”) were confiscated by the master at arms and placed in a special bag. These items were later auctioned offâthe funds used for the general welfare of the crewâthereby making those Sailors fortunate enough to obtain new items for relatively little money “lucky.”

This practice, of course, led to a varied assortment of unrelated items in the bag. Together, as representations of the personal lives of the Sailors who once owned them, these items might tell something about a ship's crew. Here, too, in this chapter are a variety of items unrelated except that they are all parts of the heritage of the U.S. Navy. Together, they tell some important and interesting things about this Navy.

It was several minutes past midnight on 15 July 1967. A quarter moon had earlier slipped behind heavy clouds gathering over the South China Sea. The resulting darkness was welcomed by the crew of trawler number 459, making their way along the coast of South Vietnam near Cape Batangan; the darker it was, the less chance they would be spotted by American or South Vietnamese coastal patrol units. The Communist vessel was laden with ninety tons of arms, ammunition, and various other supplies, enough to keep a Vietcong regiment going for several months.

What these infiltrators did not know was that the destroyer escort USS

Wilhoite

had been lurking just beyond the horizon, keeping track of the North Vietnamese trawler by radar ever since a Navy P-2 aircraft had discovered her four days earlier. Because the trawler had no radar of her own, her master had no way of knowing that he was being stalked.

Trawler 459 had been moving up and down the South Vietnamese coast for days, carefully staying out in international waters, waiting for the right

moment to run to shore undetected. Her crew had placed fishing nets on her decks to disguise her real purpose.

Unaware of her stalker and under the cover of the darkness, the trawler made her move, turning toward the shore and heading for the mouth of the Sa Ky River. At first, all was quiet, and the Communist infiltrators must have been feeling optimistic. Their hopes were soon shattered, however, when out of the shadows emerged the ominous shapes of several vessels of varying size. The Americans had sprung a trap. A Swift boat, the patrol gunboat USS

Gallup,

and the Coast Guard cutter

Point Orient

joined

Wilhoite.

All were elements assigned to the Coastal Surveillance Force (dubbed “Operation Market Time”).

Illumination flares suddenly glared out of the darkness, bathing the sea in a ghostly light, and a loudspeaker blared out a call for the intruder to heave to and surrender. But the trawler maintained course and speed in a desperate run for the shore. Two of the U.S. vessels opened fire, sending hyphenated tracers across the Communist ship's bow. This warning too was ignored. The on-scene commander gave the order to engage, and six .50-caliber machine guns, two mortars, and a 3-inch/50-caliber gun opened fire on the North Vietnamese trawler. The intruder returned fire with her 12.7-mm deck guns and a 57-mm recoilless rifle. The fight was on.

The trawler was soon taking the worst of it. The incessant fire of the American vessels chewed mercilessly at her hull and superstructure. When two helicopter gunships arrived, the enemy's fate was sealed. Soon, fires raged from stem to stern on the hapless ship.

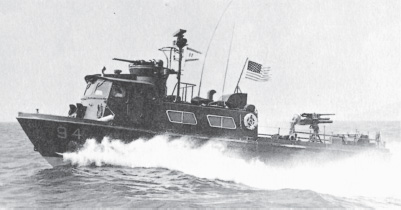

U.S. Navy Swift boats were an important element of Operation Market Time during the Vietnam War.

U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

The trawler ran aground near the mouth of the Sa Ky River and continued to burn throughout the night, the flames reflecting off the clouds of the tropical night sky in an eerie pyrotechnic dance. In the morning, when the Americans were able to board the enemy ship, they were amazed to find that several tons of ammunition had not ignited and were still intact.

It had been a successful operation by any standard. By waiting until the enemy vessel had moved into the territorial waters of South Vietnam, the Americans had adapted to the restrictions placed upon them by international law. By remaining over the horizon while stalking the enemy, the U.S. Sailors had put their technological advantage to good tactical use. By ferociously engaging the intruder when the time came, they ensured that the mission was successfully accomplished and that important supplies would not be delivered to enemy units ashore.

But there was anotherâless glamorous, but no less importantâaspect to this story. In an article published in the U.S. Naval Institute's

Proceedings

magazine in September 1968, the commander of the operation, Charles Stephan, described what happened and gave appropriate credit to the warriors who fought the battle and prevailed. He also noted that maintaining the Market Time barrier against other possible infiltrators was extremely important. In that light, he added: “But a special word of praise is in order for the

Pledge

[a U.S. minesweeper on patrol nearby] and those Swift boats that patrolled within eye and earshot of the action, and, overcoming with exemplary discipline, an almost irrepressible urge to join the battle, maintained the integrity of their patrols. They also serve.”

Commander Stephan's words illustrate an easily overlooked aspect of the U.S. Navy's heritage. This book and many others focus a great deal of attention on heroism in battle and exemplary performance in stressful situations. While this is appropriateâthe Navy exists to be ready for those moments when defending the nation requires extraordinary featsâit does not properly acknowledge that many Sailors, through no fault of their own, are never confronted with those extraordinary situations that we love to read about. Yet without those who day in and day out do the

ordinary,

there would be no

extraordinary

to celebrate.

As Commander Stephan pointed out, they also serve who maintain uneventful patrols when, not far away, a major battle is raging. They also serve who run the oilers and the ammunition ships all over the world to keep the warships supplied with what they need. They also serve who fly the CODs out to the carriers, delivering mail from home and aircraft maintenance parts. They also serve who provide medical care, cook meals, repair showers, keep pay records, update software, swab decks, lay down fixes, build runways in jungles, gather intelligence, man lecterns, lubricate

machinery, splice lines, prepare correspondence, contribute to charity events, drive vehicles ashore, and steer the ship at sea.

Still others serve the Navy and the nationâsometimes the well-being of all mankindâby stepping outside the bounds of routine; their actions are noncombatant in nature but are nonetheless bold or daring. These are Sailors who have gone where others had feared to go or simply had not thought of going. It was Sailors who first went to the North Pole in 1909 and later made the first flight over it in 1926. The Wilkes expedition was a nineteenth-century Navy-sponsored exploration of the Pacific that traveled more than eighty thousand miles, surveyed 280 islands, made the first sighting of the continent of Antarctica, and brought back huge amounts of data that advanced the world's knowledge in the fields of hydrography, geology, meteorology, botany, zoology, and ethnography. Sailors explored the Dead Sea, the Amazon River, the Isthmus of Panama, and many other parts of the world. As of this writing, the number of Sailors who have gone into outer space approaches one hundred, a point of great pride within the Navy. And every one of the astronauts who flew the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo missions that led to the landing on the Moon was retrieved from the sea upon their return to Earth by naval task forces manned by thousands of Sailors.

All Sailors, whether they do the usual or the unusual, whether they labor ashore, ply the world's seas, penetrate an ocean's depths, soar the blue skies, or venture into the blackness of space, serve the nation with every watch they stand, every duty they carry out, every moment they stand ready to do what is required. And even though danger, boredom, exhaustion, and sacrifice are often their shipmates, Sailors have the satisfaction of knowing that their “job” is more than an occupation. They know that they do more than simply earn a paycheck. They also

serve.

Most schoolchildren know that Ferdinand Magellan was the commander of the first voyage to go around the world. Like Columbus, this Portuguese mariner believed he could get to the lucrative Spice Islands to the east by sailing west and circling the globe. Like Columbus, he believed the world was much smaller than it actually is. Also like Columbus, he sailed under a Spanish flag, setting out in September 1519 with five ships (

Trinidad, San Antonio, Concepción, Victoria,

and

Santiago

) and 270 men under his command.