A Short History of the World (35 page)

Read A Short History of the World Online

Authors: H. G. Wells

European Aggression in Asia, and the Rise of Japan

It is difficult to believe that any large number of people really accepted this headlong painting of the map of Africa in European colours as a permanent new settlement of the world's affairs, but it is the duty of the historian to record that it was so accepted. There was but a shallow historical background to the European mind in the nineteenth century, and no habit of penetrating criticism. The quite temporary advantages that the mechanical revolution in the West had given the Europeans over the rest of the old world were regarded by people, blankly ignorant of such events as the great Mongol conquests, as evidences of a permanent and assured European leadership of mankind. They had no sense of the transferability of science and its fruits. They did not realize that Chinamen and Indians could carry on the work of research as ably as Frenchmen or Englishmen. They believed that there was some innate intellectual drive in the West, and some innate indolence and conservatism in the East, that assured the Europeans a world predominance for ever.

The consequence of this infatuation was that the various European foreign offices set themselves not merely to scramble with the British for the savage and undeveloped regions of the world's surface, but also to carve up the populous and civilized countries of Asia as though these people also were no more than raw material for exploitation. The inwardly precarious but outwardly splendid imperialism of the British ruling class in India, and the extensive and profitable possessions of the Dutch in the East Indies, filled the rival Great Powers with dreams of similar glories in Persia, in the disintegrating Ottoman Empire, and in Further India, China and Japan.

In 1898 Germany seized Kiau Chau in China. Britain responded by seizing Wei-hai-wei, and the next year the Russians took possession of Port Arthur. A flame of hatred for the Europeans swept through China. There were massacres of Europeans and Christian converts, and in 1900 an attack upon and siege of the European legations in Pekin. A combined force of Europeans made a punitive expedition to Pekin, rescued the legations and stole an enormous amount of valuable property. The Russians then seized Manchuria, and in 1904 the British invaded Tibetâ¦

But now a new Power appeared in the struggle of the Great Powers, Japan. Hitherto Japan has played but a small part in this history; her secluded civilization has not contributed very largely to the general shaping of human destinies; she has received much, but she has given little. The Japanese proper are of the Mongolian race. Their civilization, their writing, and their literary and artistic traditions are derived from the Chinese. Their history is an interesting and romantic one; they developed a feudal system and a system of chivalry in the earlier centuries of the Christian era; their attacks upon Korea and China are an Eastern equivalent of the English wars in France. Japan was first brought into contact with Europe in the sixteenth century; in 1542 some Portuguese reached it in a Chinese junk, and in 1549 a Jesuit missionary, Francis Xavier, began his teaching there. For a time Japan welcomed European intercourse, and the Christian missionaries made a great number of converts. A certain William Adams became the most trusted European adviser of the Japanese, and showed them how to build big ships. There were voyages in Japanese-built ships to India and Peru. Then arose complicated quarrels between the Spanish Dominicans, the Portuguese Jesuits, and the English and Dutch Protestants, each warning the Japanese against the political designs of the others. The Jesuits in a phase of ascendancy, persecuted and insulted the Buddhists with great acrimony. In the end the Japanese came to the conclusion that the Europeans were an intolerable nuisance, and that Catholic Christianity in particular was a mere cloak for the political dreams of the Pope and the Spanish monarchy â already in

possession of the Philippine Islands; there was a great persecution of the Christians, and in 1638 Japan was absolutely closed to Europeans, and remained closed for over 200 years. During those two centuries the Japanese were as completely cut off from the rest of the world as though they lived upon another planet. It was forbidden to build any ship larger than a mere coasting boat. No Japanese could go abroad, and no European enter the country.

For two centuries Japan remained outside the main current of history. She lived on in a state of picturesque feudalism in which about 5 per cent of the population, the

samurai

, or fighting men, and the nobles and their families, tyrannized without restraint over the rest of the population. Meanwhile the great world outside went on to wider visions and new powers. Strange shipping became more frequent, passing the Japanese headlands; sometimes ships were wrecked and sailors brought ashore. Through the Dutch settlement in the island of Deshima, their one link with the outer universe, came warnings that Japan was not keeping pace with the power of the Western world. In 1837 a ship sailed into Yedo Bay flying a strange flag of stripes and stars, and carrying some Japanese sailors she had picked up far adrift in the Pacific. She was driven off by cannon shot. This flag presently reappeared on other ships. One in 1849 came to demand the liberation of eighteen shipwrecked American sailors. Then in 1853 came four American warships under Commodore Perry, and refused to be driven away. He lay at anchor in forbidden waters, and sent messages to the two rulers who at that time shared the control of Japan. In 1854 he returned with ten ships, amazing ships propelled by steam, and equipped with big guns, and he made proposals for trade and intercourse that the Japanese had no power to resist. He landed with a guard of 500 men to sign the treaty. Incredulous crowds watched this visitation from the outer world, marching through the streets.

Russia, Holland and Britain followed in the wake of America. A great nobleman whose estates commanded the Straits of Shimonoseki saw fit to fire on foreign vessels, and a bombardment by a fleet of British, French, Dutch and American warships

destroyed his batteries and scattered his swordsmen. Finally an allied squadron (1865), at anchor off Kioto, imposed a ratification of the treaties which opened Japan to the world.

The humiliation of the Japanese by these events was intense. With astonishing energy and intelligence they set themselves to bring their culture and organization to the level of the European powers. Never in all the history of mankind did a nation make such a stride as Japan then did. In 1866 she was a medieval people, a fantastic caricature of the extremest romantic feudalism; in 1899 hers was a completely Westernized people, on a level with the most advanced European powers. She completely dispelled the persuasion that Asia was in some irrevocable way hopelessly behind Europe. She made all European progress seem sluggish by comparison.

We cannot tell here in any detail of Japan's war with China in 1894â95. It demonstrated the extent of her Westernization. She had an efficient Westernized army and a small but sound fleet. But the significance of her renascence, though it was appreciated by Britain and the United States, who were already treating her as if she were a European state, was not understood by the other Great Powers engaged in the pursuit of new Indias in Asia. Russia was pushing down through Manchuria to Korea. France was already established far to the south in Tonkin and Annam, Germany was prowling hungrily on the lookout for some settlement. The three powers combined to prevent Japan reaping any fruits from the Chinese war. She was exhausted by the struggle, and they threatened her with war.

Japan submitted for a time and gathered her forces. Within ten years she was ready for a struggle with Russia, which marks an epoch in the history of Asia, the close of the period of European arrogance. The Russian people were, of course, innocent and ignorant of this trouble that was being made for them halfway round the world, and the wiser Russian statesmen were against these foolish thrusts; but a gang of financial adventurers, including the Grand Dukes, his cousins, surrounded the Tzar. They had gambled deeply in the prospective looting of Manchuria and China, and they would suffer no withdrawal. So there began a transportation of great armies of Japanese soldiers

across the sea to Port Arthur and Korea, and the sending of endless trainloads of Russian peasants along the Siberian railway to die in those distant battlefields.

The Russians, badly led and dishonestly provided, were beaten on sea and land alike. The Russian Baltic Fleet sailed round Africa to be utterly destroyed in the Straits of Tshushima. A revolutionary movement among the common people of Russia, infuriated by this remote and reasonless slaughter, obliged the Tzar to end the war (1905); he returned the southern half of Saghalien, which had been seized by Russia in 1875, evacuated Manchuria, resigned Korea to Japan. The European invasion of Asia was coming to an end and the retraction of Europe's tentacles was beginning.

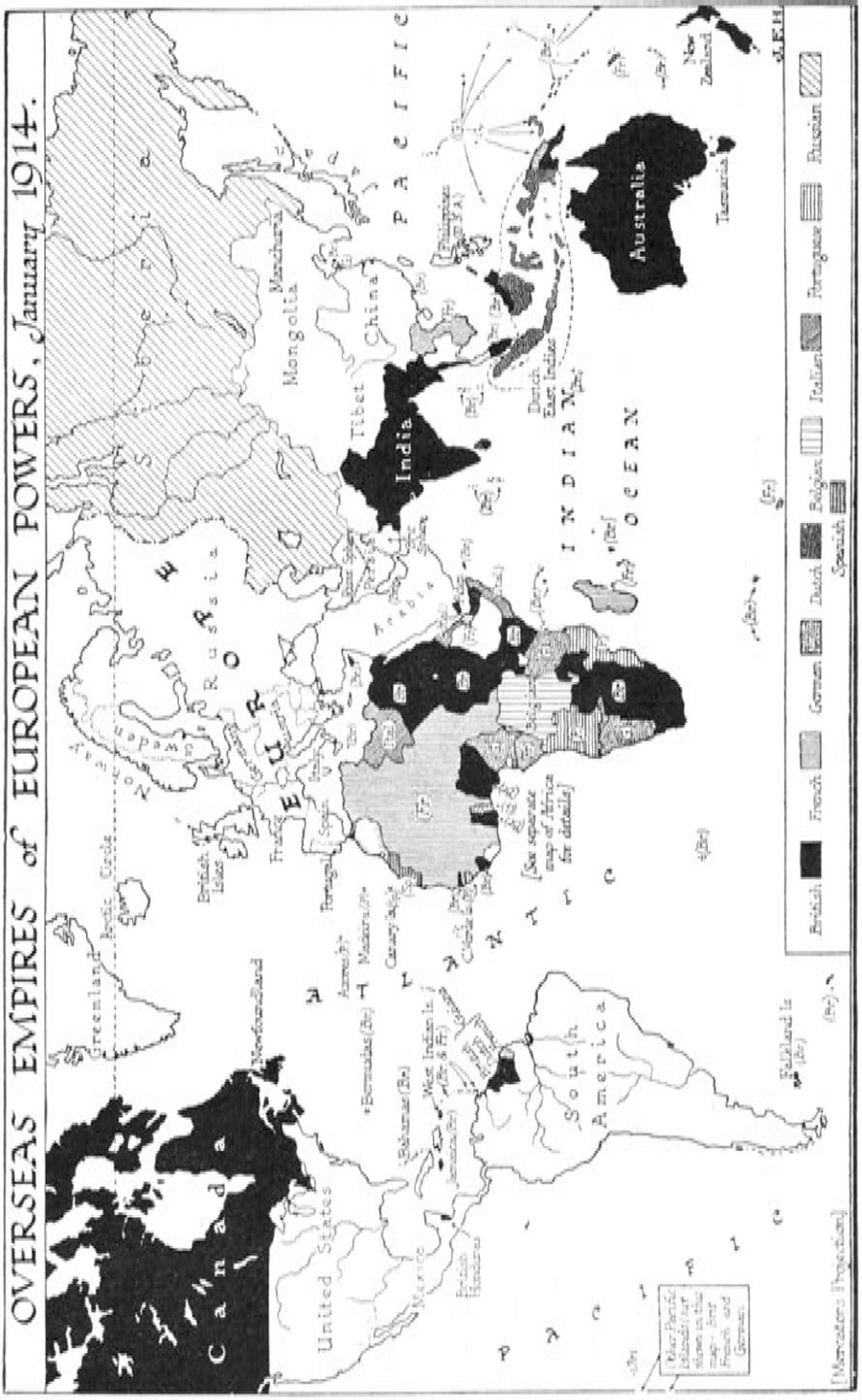

The British Empire in 1914

We may note here briefly the varied nature of the constituents of the British Empire in 1914 which the steamship and railway had brought together. It was and is a quite unique political combination; nothing of the sort has ever existed before.

First and central to the whole system was the ‘crowned republic’ of the United British Kingdom, including (against the will of a considerable part of the Irish people) Ireland.

1

The majority of the British Parliament, made up of the three united parliaments of England and Wales, Scotland and Ireland, determines the headship, the quality and policy of the ministry, and determines it largely on considerations arising out of British domestic politics. It is this ministry which is the effective supreme government, with powers of peace and war, over all the rest of the Empire.

Next in order of political importance to the British States were the ‘crowned republics’ of Australia, Canada, Newfoundland (the oldest British possession, 1583), New Zealand and South Africa, all practically independent and self-governing states in alliance with Great Britain, but each with a representative of the Crown appointed by the Government in office;

Next the Indian Empire, an extension of the Empire of the Great Mogul, with its dependent and ‘protected’ states reaching now from Baluchistan to Burma, and including Aden,

2

in all of which empire the British Crown

and

the India Office (under Parliamentary control) played the role of the original Turkoman dynasty;

Then the ambiguous possession of Egypt,

3

still nominally a part of the Turkish Empire and still retaining its own monarch, the Khedive, but under almost despotic British official rule;

Then the still more ambiguous ‘Anglo-Egyptian’ Sudan

4

province, occupied and administered jointly by the British and by the (British controlled) Egyptian government;

Then a number of partially self-governing communities, some British in origin and some not, with elected legislatures and an appointed executive, such as Malta, Jamaica, the Bahamas and Bermuda;

5

Then the Crown colonies, in which the rule of the British Home government (through the Colonial Office) verged on autocracy, as in Ceylon, Trinidad and Fiji

6

(where there was an appointed council), and Gibraltar and St Helena (where there was a governor);

Then great areas of (chiefly) tropical lands, raw-product areas, with politically weak and undercivilized native communities, which were nominally protectorates, and administered either by a High Commissioner set over native chiefs (as in Basutoland) or over a chartered company (as in Rhodesia).

7

In some cases the Foreign Office, in some cases the Colonial Office, and in some cases the India Office, has been concerned in acquiring the possessions that fell into this last and least definite class of all, but for the most part the Colonial Office was now responsible for them.

It will be manifest, therefore, that no single office and no single brain had ever comprehended the British Empire as a whole. It was a mixture of growths and accumulations entirely different from anything that has ever been called an empire before. It guaranteed a wide peace and security; that is why it was endured and sustained by many men of the ‘subject’ races – in spite of official tyrannies and insufficiencies, and of much negligence on the part of the ‘home’ public. Like the Athenian empire, it was an overseas empire; its ways were sea ways, and its common link was the British navy. Like all empires, its cohesion was dependent physically upon a method of communication; the development of seamanship, shipbuilding and steamships between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries had made it a possible and convenient Pax – the ‘Pax Britannica’, and fresh developments of air or swift land transport might at any time make it inconvenient.

The Age of Armament in Europe, and the Great War of 1914â18

The progress in material science that created this vast steam-boat-and-railway republic of America and spread this precarious British steamship empire over the world, produced quite other effects upon the congested nations upon the continent of Europe. They found themselves confined within boundaries fixed during the horse-and-high-road period of human life, and their expansion overseas had been very largely anticipated by Great Britain. Only Russia had any freedom to expand eastward; and she drove a great railway across Siberia until she entangled herself in a conflict with Japan, and pushed south-eastwardly towards the borders of Persia

1

and India to the annoyance of Britain. The rest of the European powers were in a state of intensifying congestion. In order to realize the full possibilities of the new apparatus of human life they had to rearrange their affairs upon a broader basis, either by some sort of voluntary union or by a union imposed upon them by some predominant power. The tendency of modern thought was in the direction of the former alternative, but all the force of political tradition drove Europe towards the latter.

The downfall of the âempire' of Napoleon III, the establishment of the new German Empire, pointed men's hopes and fears towards the idea of a Europe consolidated under German auspices. For thirty-six years of uneasy peace the politics of Europe centred upon that possibility. France, the steadfast rival of Germany for European ascendancy since the division of the empire of Charlemagne, sought to correct her own weakness by a close alliance with Russia, and Germany linked herself closely with the Austrian empire (it had ceased to be the Holy

Roman Empire in the days of Napoleon I) and less successfully with the new kingdom of Italy. At first Great Britain stood as usual half in and half out of continental affairs. But she was gradually forced into a close association with the Franco-Russian group by the aggressive development of a great German navy. The grandiose imagination of the Emperor William II (1888â1918) thrust Germany into premature overseas enterprise that ultimately brought not only Great Britain but Japan and the United States into the circle of her enemies.

All these nations armed. Year after year the proportion of national production devoted to the making of guns, equipment, battleships and the like, increased. Year after year the balance of things seemed trembling towards war, and then war would be averted. At last it came. Germany and Austria struck at France and Russia and Serbia; the German armies marching through Belgium, Britain immediately came into the war on the side of Belgium, bringing in Japan as her ally, and very soon Turkey followed on the German side. Italy entered the war against Austria in 1915, and Bulgaria joined the Central Powers in the October of that year. In 1916 Rumania, and in 1917 the United States and China were forced into war against Germany. It is not within the scope of this history to define the exact share of blame for this vast catastrophe. The more interesting question is not why the Great War was begun but why the Great War was not anticipated and prevented. It is a far graver thing for mankind that scores of millions of people were too âpatriotic', stupid, or apathetic to prevent this disaster by a movement towards European unity upon frank and generous lines, than that a small number of people may have been active in bringing it about.

It is impossible within the space at our command here to trace the intricate details of the war. Within a few months it became apparent that the progress of modern technical science had changed the nature of warfare very profoundly. Physical science gives power, power over steel, over distance, over disease; whether that power is used well or ill depends upon the moral and political intelligence of the world. The governments of Europe, inspired by antiquated policies of hate and suspicion,

found themselves with unexampled powers both of destruction and resistance in their hands. The war became a consuming fire round and about the world, causing losses both to victors and vanquished out of all proportion to the issues involved. The first phase of the war was a tremendous rush of the Germans upon Paris and an invasion of east Prussia by the Russians. Both attacks were held and turned. Then the power of the defensive developed; there was a rapid elaboration of trench warfare until for a time the opposing armies lay entrenched in long lines right across Europe, unable to make any advance without enormous losses. The armies were millions strong, and behind them entire populations were organized for the supply of food and munitions to the front. There was a cessation of nearly every sort of productive activity except such as contributed to military operations. All the able-bodied manhood of Europe was drawn into the armies or navies or into the improvised factories that served them. There was an enormous replacement of men by women in industry. Probably more than half the people in the belligerent countries of Europe changed their employment altogether during this stupendous struggle. They were socially uprooted and transplanted. Education and normal scientific work were restricted or diverted to immediate military ends, and the distribution of news was crippled and corrupted by military control and âpropaganda' activities.

The phase of military deadlock passed slowly into one of aggression upon the combatant populations behind the fronts by the destruction of food supplies and by attacks through the air. And also there was a steady improvement in the size and range of the guns employed and of such ingenious devices as poison-gas shells and the small mobile forts known as tanks, to break down the resistance of troops in the trenches. The air offensive was the most revolutionary of all the new methods. It carried warfare from two dimensions into three. Hitherto in the history of mankind war had gone on only where the armies marched and met. Now it went on everywhere. First the Zeppelin and then the bombing aeroplane carried war over and past the front to an ever-increasing area of civilian activities beyond. The old distinction maintained in civilized warfare

between the civilian and combatant population disappeared. Everyone who grew food, or who sewed a garment, everyone who felled a tree or repaired a house, every railway station and every warehouse was held to be fair game for destruction. The air offensive increased in range and terror with every month in the war. At last great areas of Europe were in a state of siege and subject to nightly raids. Such exposed cities as London and Paris passed sleepless night after sleepless night while the bombs burst, the anti-aircraft guns maintained an intolerable racket, and the fire engines and ambulances rattled headlong through the darkened and deserted streets. The effects upon the minds and health of old people and of young children were particularly distressing and destructive.

Pestilence, that old follower of warfare, did not arrive until the very end of the fighting in 1918. For four years medical science staved off any general epidemic; then came a great outbreak of influenza about the world which destroyed many millions of people.

2

Famine also was staved off for some time. By the beginning of 1918, however, most of Europe was in a state of mitigated and regulated famine. The production of food throughout the world had fallen very greatly through the calling off of peasant mankind to the fronts, and the distribution of such food as was produced was impeded by the havoc wrought by the submarine, by the rupture of customary routes through the closing of frontiers, and by the disorganization of the transport system of the world. The various governments took possession of the dwindling food supplies and, with more or less success,

rationed

their populations. By the fourth year the whole world was suffering from shortages of clothing and housing and of most of the normal gear of life as well as of food. Business and economic life were profoundly disorganized. Everyone was worried, and most people were leading lives of unwonted discomfort.

The actual warfare ceased in November 1918. After a supreme effort in the spring of 1918 that almost carried the Germans to Paris, the Central Powers collapsed. They had come to the end of their spirit and resources.