A Singular Woman (5 page)

That trip, he said, probably helped ensure that he and his siblings left Augusta behind them “almost as soon as we could.”

Madelyn's father, Rolla Charles Payne, had grown up on his family's farm in Olathe and had gone to work for the Sinclair Oil and Gas Company as a bookkeeper and later as district clerk in Augusta. (The name Rolla, which rhymes with “wallah,” is said to have ranked among the top five hundred most popular boys' names for a time near the end of the nineteenth century. Rolla Payne, however, did not love it. He went by the initials R.C. or simply Payne, the name by which Leona addressed him.) A veteran of World War I, R. C. Payne appears to have met Leona McCurry in Independence, where they were living and working. They received a marriage license in December 1921, and their first child, Madelyn Lee, was born on October 26, 1922, in Peru. By the time Charles and Margaret Arlene were born several years later, the family had moved to Augusta, another former farming community transformed by oil, eighteen miles southwest of El Dorado. By the end of World War I, there were three refineries in Augusta and ten thousand people living within a five-mile radiusâfrom the families of oil company executives to laborers on the oil leases and a small community of Mexicans employed by the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway and living in an enclave bounded by the Walnut River, South Osage Street, and the Santa Fe tracks. A two-lane brick highway to Wichita opened in 1924, the year a twister roared into town, tore a corner off the high school, and demolished a Catholic church. Jon Payne, the youngest of the four Payne children, who spent his entire childhood in Augusta until his parents moved during his senior year in high school to a tiny oil-field community called Thrall, said he had never met a black person until he went away to college at the University of Kansas.

Butler County was almost entirely white and Christian when Madelyn Payne was growing up in Augusta and Stanley Dunham in El Dorado in the 1920s and 1930s. Recruiters for the Ku Klux Klan moved into the county in the early 1920s, billing the Klan as a patriotic Christian benevolent association. Roxie Olmstead, who grew up in Butler County and later did some research on the Klan, found that the organization advanced north from Oklahoma, recruiting what it called “native born, white, Protestant, Gentile, American” citizens. Klan chapters met in churches, held initiation ceremonies in robes and on horseback, and burned crosses. The focus was moral issues, Roxie Olmstead reported in a paper available at the Butler County Historical Society, such as “faithless husbands and wives in Augusta.” There was a Klan parade in Augusta in September 1923; a meeting in El Dorado in August 1924 reportedly attracted three thousand people. The name of the Kaffir Corn Carnival was changed, for 1924 only, to the Kaffir Korn Karnival. William Allen White, who had been editorializing against the Klan since 1921 in

The Emporia Gazette,

ran as an independent candidate for governor in 1924 on what for much of the campaign was an anti-Klan platform. He came in third out of three, but historians say his campaign weakened the Klan. The following year, the state supreme court banned it from operating in Kansas.

The Emporia Gazette,

ran as an independent candidate for governor in 1924 on what for much of the campaign was an anti-Klan platform. He came in third out of three, but historians say his campaign weakened the Klan. The following year, the state supreme court banned it from operating in Kansas.

For much of Madelyn's childhood, the family lived in a single-story wood-frame house owned by the Sinclair Oil and Gas Company, and next door to the office where her father, R. C. Payne, worked. The house had three bedrooms, one bathroom, a living room, a dining room, a kitchen, and a screened-in back porch, where Charles sometimes slept on a cot. Space was tight. Aunt Ruth McCurry, the teacher, came to stay every summer, bunking in the girls' room. Stanley Ann, as an infant and toddler, lived there during World War II while her father was in the Army and her mother commuted to Wichita for work. Out back, there was a pipe yard and a net for “moonlight basketball.” Baseball was played in a nearby vacant lot. Jon Payne remembered helping his mother wash the laundry in a couple of round Maytag washers equipped with wringers and watching the sheets freeze in winter. It was an easy walk along the tree-lined brick streets into town, where there were drugstores with soda fountains and booths, a couple of them with jukeboxes stocked by the late 1930s with the music of Glenn Miller, Benny Goodman, and Tommy Dorsey, and even a small floor for dancing. In the booths, some of the high school students played bridge. During the Depression, people in Augusta went to the movies several times a week. There were cowboy movies at the Isis Theatre on weekends, and the Augusta Theatre, which opened in the summer Madelyn was twelve, was the first to be lit entirely by neon. People flocked to movies starring Bette Davis, from whom teenage girls picked up a veneer of sophistication and learned how to hold a cigarette for maximum glamorous effect. For a time, an instructor from a dance studio in Wichita came in to teach a dozen children ballroom dancing and the jitterbug on the stage of the theater. On Sundays, the Paynes attended the Methodist church. They were not poorâMr. Payne worked through the Depressionâbut there was never a lot of money. Madelyn's brother Charles worked in a grocery store up to twenty hours a week and full-time in summer all through high school. Jon was probably in the eighth grade, he said, before he wore “store-bought pants.” Leona made many of her children's clothes. Charles Payne, a lifelong Democrat, told me that his mother's family voted Republican but that his father was a Democrat. He remembered the family listening to radio broadcasts of the inauguration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933 and later his fireside chats. When Alf Landon, the then governor of Kansas, became the Republican presidential nominee running against Roosevelt in the 1936 election, the Paynes backed him: “We were waving sunflower flags.”

Augusta, with a population of several thousand, was not the cul-de-sac that the small-town Kansas stereotype might summon to mind. Mack Gilkeson, who grew up in Augusta and knew both Madelyn Payne as a child and Stanley Dunham as a teenager, went on to become a professor of chemical engineering in California and a consultant in places like Papua New Guinea. As many as half of his high school classmates, he said, eventually moved away. Their teachers encouraged students who were academically gifted. Asked when he had first felt the urge to move beyond Butler County, he said, “I was led on that path.” Members of Stanley and Madelyn's generation not only left Augusta behind, they abandoned their parents' political views. Mack Gilkeson's parents were Republicans, as was everybody they knew. When they went to Topeka to visit a relative who worked for the newspaper chain owned by the Republican United States senator from Kansas, Arthur Capper, Mack was under orders not to utter the name Roosevelt. That sort of rigidity did not appeal to him. “I just found it distasteful,” he said. “When I encountered it, I would say, âThat's not what I'm going to do.'” Because there were no private or parochial schools, everyone in Augusta went to the same high schoolâchildren of bank presidents, oil company executives, doctors, farmers, and oil-field workers. “I suppose that led me to be more egalitarian than I would have been from other circumstances,” Gilkeson said. Children reared in Augusta had some understanding of class differences. Virginia Dashner Ewalt, an oil pumper's daughter who grew up on the Sinclair oil lease southeast of Augusta and was in the Augusta High School senior-class play with Madelyn, went to elementary school with twenty other children in a one-room schoolhouse heated by a single large coal-burning stove. “Country kids were a little different,” she said. She sometimes felt a distinct chill from some of the crowd that had grown up in Augusta.

Leona and R. C. Payne had expectations for their children. They were to be good, study hard, get good marks, and make something of themselves. “My mother had high aspirations,” said Margaret Arlene Payne, who got a bachelor's degree from the University of Kansas, a master's degree from Teachers College of Columbia University, and a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. The message was, Arlene said, “You're going to college. And there's no question.” Jon, Madelyn's youngest brother, said, “I don't think they had an expectation of us staying in Kansas. I think they expected much more out of usâto get to college and then do whatever you could.” But the Depression and the shadow of war colored the children's sense of their future. Clarence Kerns, historian for the El Dorado High School class of 1935, said there were so few jobs available when his class graduated that nine of his classmates became ministers. Many others became teachers in one-room schoolhouses across Kansas. Few went straight to college. Long-range planning seemed pointless. “The news month by month was always bad,” said Mack Gilkeson, recalling the years leading up to and during World War II. “You'd go out and get the morning paper at seven a.m. and look at the headline. It would be: âThe Germans have invaded Norway. The Germans have invaded Greece. The Allies are retreating. Things are going bad in North Africa.' The future was very uncertain. So you would make the decision, âI'm going to do this,' and not worry about what two years from now will bring.” Some couples married early, craving permanence. Girls who had expected to go straight to college, instead had to find work. “I can remember Madelyn fretting over the fact that some of her friends, who were more well-to-do than we, were planning to go to some fancy college or other, and she knew she couldn't,” Charles remembered. “So the question was: Would she go to the local junior college? Should she go to work? That sort of thing.” As for himself, he said, “I knew from about the seventh grade on that there was going to be a war and I was going to be in it. So I never really thought a whole lot about going to college, because I just figured, âOkay, I'll grow up and I'm going to go off to war.' Truth is, I didn't really expect to survive it.”

R. C. Payne had a particular attachment to his firstborn daughter, according to her brother Jon, who was born fifteen years later. She was the only child born in Peru before Mr. Payne's job brought the family to Augusta. A notice published in the

Sedan Times-Star

on November 22, 1922, announced, “Charles R. Payne [

sic

] and wife are rejoicing over the arrival of little Madelyn Lee, an 8 lb daughter.” She was bright, lively, and strong-willed. She got good grades if she wanted to, Charles Payne said, but she was not above taking off the occasional school-day afternoon with a friend, precipitating a row with her mother, who wanted her children to do their best at all times, not just when they felt like it. Slender, tidy, and well turned out, Madelyn affected a kind of worldliness, at least toward her siblings. “Madelyn in high school always had boyfriendsâusually a couple, maybe three different ones,” Charles said. “She was nice-enough-looking, no great beauty, and quite vivacious, lively, and fun. Her various boyfriends bored her, to tell you the truth. They were Kansas boys. She tended to view herself more as a Bette Davis type.” By her senior year in high school, with the country stuck in the Depression and war on the horizon, Madelyn's options for higher education may have looked limited, at least in the short run. “I think she was looking for a more exciting life, wanting to escape small-town Kansas,” Charles said. “And I think she really didn't see her own future. She didn't see anything other than going to school and getting a teaching certificate, which my mother assumed she would do, because that was what she had done. It was either that or be a clerk in the dry goods store.”

Sedan Times-Star

on November 22, 1922, announced, “Charles R. Payne [

sic

] and wife are rejoicing over the arrival of little Madelyn Lee, an 8 lb daughter.” She was bright, lively, and strong-willed. She got good grades if she wanted to, Charles Payne said, but she was not above taking off the occasional school-day afternoon with a friend, precipitating a row with her mother, who wanted her children to do their best at all times, not just when they felt like it. Slender, tidy, and well turned out, Madelyn affected a kind of worldliness, at least toward her siblings. “Madelyn in high school always had boyfriendsâusually a couple, maybe three different ones,” Charles said. “She was nice-enough-looking, no great beauty, and quite vivacious, lively, and fun. Her various boyfriends bored her, to tell you the truth. They were Kansas boys. She tended to view herself more as a Bette Davis type.” By her senior year in high school, with the country stuck in the Depression and war on the horizon, Madelyn's options for higher education may have looked limited, at least in the short run. “I think she was looking for a more exciting life, wanting to escape small-town Kansas,” Charles said. “And I think she really didn't see her own future. She didn't see anything other than going to school and getting a teaching certificate, which my mother assumed she would do, because that was what she had done. It was either that or be a clerk in the dry goods store.”

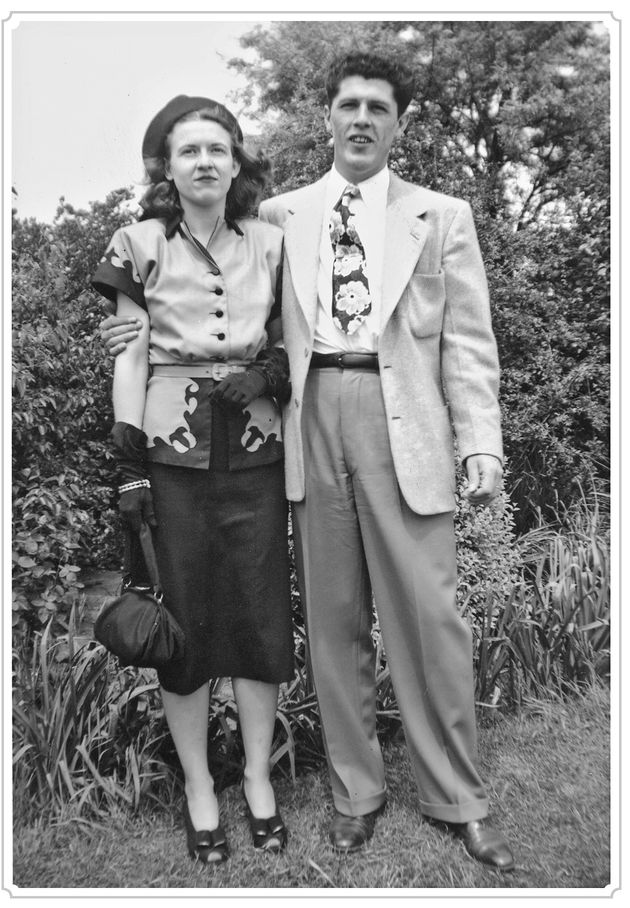

Stanley Dunham, flamboyant and seemingly worldly, may have looked like just the ticket. After dropping out of high school, he had hit the road for a time. According to Ralph, Stanley, who was four years older than Madelyn, had gone to California and spent some time with a Kansas friend who later became a Hollywood writer. He returned to Kansas, others said, with grand tales of hobnobbing with John Steinbeck, various playwrights, and other California writers of the 1930s. He seemed to have left the impression, at least with Madelyn, that he had a trunk full of plays and the possibility of a literary futureâeven if, for the time being, he was doing construction at the Socony refinery in Augusta. “He wrote plays and poetry, and he would come over to our house and read them to us,” Arlene Payne remembered. “It was, I'm sure, all very exotic to her.” Though El Dorado and Augusta were archrivals in football and baseball, it was not uncommon for El Dorado boys to date girls from Augusta and vice versa. It is unclear exactly how or when Stanley and Madelyn met. When I asked Ralph Dunham what he thought drew Madelyn to his brother, he said, “Well, he was a personable guy and wasn't above telling aâ” Stopping in mid-sentence, he changed course: “You know, he was okay.” When I asked him what he had been about to say, he continued, carefully, “Well, Stanley didn't always tell things exactly like they were. But not many people do. And when you're courting, you first try to present a good side of yourself and your hopes and ambitions and all the rest.” Asked the same question, Jon Payne said, laughing, “Oh, you know, 1930s Kansas, Dust Bowl, Depression, stuck in Hicksville, USA. I think she was looking at Stanley as a way of getting out of Dodge.”

Other books

A Moveable Famine by John Skoyles

A Single Date (Dating Just Got Serious) by Kelly, Jacki

1 Death Comes to Town by K.J. Emrick

Hermoso Final by Kami García, Margaret Stohl

Season's Regency Greetings by Carla Kelly

Inconstant Moon - Default Font Edition by Laurel L. Russwurm

Jaded (The Butterfly Memoirs) by Kane, M. J.

The Spinster Bride by Jane Goodger

Starman by Alan Dean Foster

Vampire Affliction by Eva Pohler