A Stranger in the Kingdom (65 page)

Read A Stranger in the Kingdom Online

Authors: Howard Frank Mosher

“I'd forgotten how small it was,” I said. “I've always thought of him as a big man.”

Nat grunted. “You were small when you saw him for the first time, so he seemed big.”

I eased the yellowing old bones out of the closet and laid them on a lab table. They glowed softly in the faint light cast up from the street below. The skeleton was as short as a child's, nearly.

We began disassembling it, stacking the individual bones without particular order inside the cardboard box. We set the skull in last. “There you go, Yorick,” Nat said.

“Look at the poor old guy,” I said. “He was missing half his teeth.”

“Let's not wax sentimental, Kinneson. No doubt he's laughing at us with the few he has left.”

We left the building through the locker room exit, stepping out into a bitter wind gusting hard between the dark looming stacks of lumber in the mill yard, and I remembered what Nat's father had said on the night I first met him outside the parsonage: “Your blooming weather is worse than Korea's!”

The door to the cemetery toolshed was padlocked, but the hasp was so old and rusty that I easily wrenched it and the lock away from the punky jamb. Inside, we found a shovel leaning in a corner.

In front of Pliny's tall monument the ground was hard with frost for an inch or so, then nearly as hard with the ubiquitous blue clay of Kingdom County. We took turns with the shovel until we were down about four feet. That was enough. As we filled the hole in, it began to snow lightly; by the time we were finished, the flakes were coming fast.

“Kinneson, we may be a pair of bloody damn fools, but I'm glad we did that,” Nathan said suddenly.

Then we were laughingâtwo middle-aged men in a snowy cemetery in an end-of-the-line little northern hill town, which was dying fast now like a thousand other hill towns, laughing the way we had laughed on those half-dozen or so other occasions in a long-ago summer when we had done something we thought was sneaky and gotten away with it.

Ten minutes later we shook hands in front of the

Monitor

, and then he was gone as suddenly as he had appeared, and I was alone on the street in the snow.

As I walked out to the gool from the village, away from the protection of the houses, the wind drove the hard pellets of snow against my face, and I huddled into my jacket as I had on the night of my thirteenth birthday when I'd met Reverend Andrews for the first time. On my right, invisible in the falling snow, was the cemetery where so many of my own ancestors lay buried, and now Pliny Templeton with them.

No ghosts accompanied me home that night, but as I stood on the red iron bridge, listening to the muffled river running below me in the snow, I thought of my great-great-great-grandfather, Charles I, who had come to the Kingdom because he loved to angle for trout.

I thought of my great-great-great-great Abenaki grandfather, Sabattis, coming up the same river in the fall of 1781 and discovering Charles I building a cabin where no man had ever built before, and I thought of Charles' Indian bride, Memphremagog, and their son James I, who with the wild Irish Fenians had launched his abortive attacks down the river against Canada.

I thought of James' son, Mad Charlie Kinneson, who had ferried runaway slaves to Canada by canoe and fought with John Brown at Harper's Ferry and finally shot and killed his best friend Pliny Templeton; and I thought of Claire LaRiviere, the daughter of Etienne, coming boldly out from the village across the river to our farmhouse kitchen on a rainy summer night in my youth.

I thought of the Dog Cart Man trotting over the bridge on a summer day and turning down the county road toward Ben Currier's. I thought how Resolvèd loved to sit under the bridge with his friend Old Duke on a hot summer afternoon, and I thought of Frenchy LaMott approaching Nat and me on the trestle half a mile downstream and Nat diving in one long perfect arc into the water and pulling Frenchy out.

All these things occurred to me as I stood on the bridge in the falling snow.

I thought too of my father's statement in the

Monitor

and Charlie's paraphrase of it in his great speech at Reverend Andrews' trial, that our Kingdom was a good but eminently improvable place, where the past was still part of the present, and for the first time in my life I believed that I fully understood what they had meant.

“We should have taken him brook trout fishing, James,” I heard my father say, his voice harsh and gravelly, as it had been that election night in 1952 after Reverend Andrews and Nat had left town and Mason White had gone back to the village to celebrate his election victory.

“Who, Reverend Andrews?” Charlie said. “Hell, he didn't care anything about fishing, Jimmy, for brook trout or anything else.”

“Just the same, James, we should have taken him,” Dad said.

They were still arguing as I headed out along the gool toward home, and the last distinct words I heard were “James” and “Jimmy.”

Â

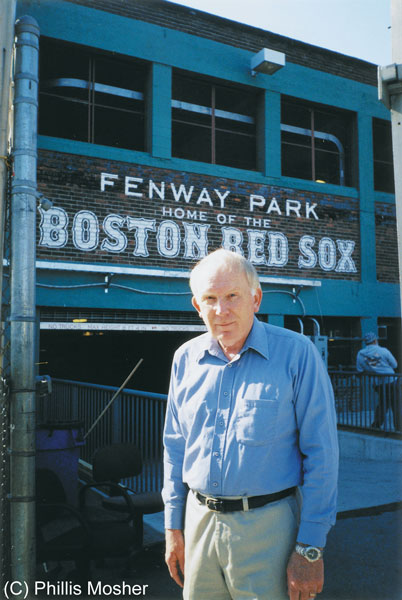

H

OWARD

F

RANK

M

OSHER

is the author of ten books, including

Waiting for Teddy Williams, The True Account,

and

A Stranger in the Kingdom,

which, along with

Disappearances,

was corecipient of the New England Book Award for fiction. He lives in Vermont.