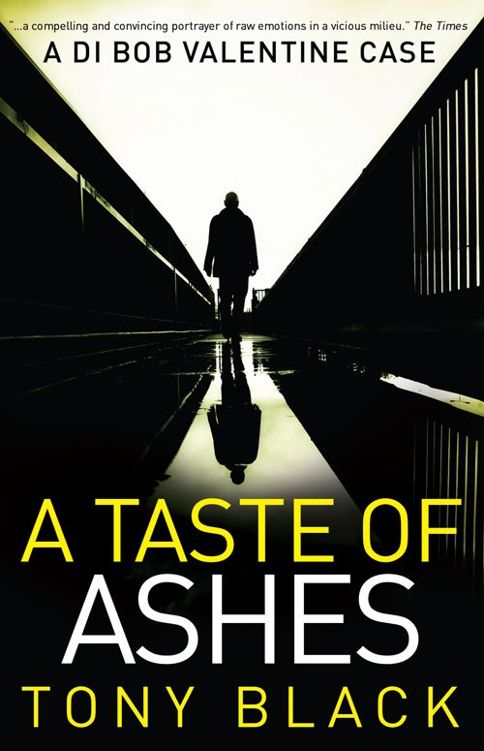

A Taste of Ashes (DI Bob Valentine Book 2)

Read A Taste of Ashes (DI Bob Valentine Book 2) Online

Authors: Tony Black

For Cheryl and Conner

I’d like to thank Dr Robert Ghent for

his assistance, once again, in helping

with the medical research. And to all at

Black & White Publishing for making

the process run so smoothly.

Agnes Gilchrist hid behind the open curtain in her front room. She’d seen some of her neighbours rushing by, grimacing, sneering at the window as they passed. When the new bus stop went in and the unruly wee brats from both ends of the street started to treat it like a gang hut, stones were thrown at her window. She called the police then, they knew her name now.

Frank was more cautious, worried about people’s opinions. He complained if she spent her time at the window, watching what went on in the street. But now he wasn’t there to complain, to tell her to get out in the world, get on with her life and leave others to theirs.

Agnes moved away from the curtain, she folded up Frank’s good suit, the brown tweed one, and put it in the carrier bag for the charity shop collection. Someone would get a wear out of it. She peered at the window once more, it was starting up again.

‘What a racket,’ she said.

Number 23 were a rowdy lot, even for this end of Whitletts. She couldn’t decide whether it had been worse with the police cars round every night of the week, before that boy joined the army. It might have been, but then was there a time when it had been truly quiet?

‘What in the name of God?’

Shouts and screams. Another disturbance. Even the mobile butcher didn’t park there now – he said it affected trade because no one wanted to queue up where a full-scale row was likely to break out at any minute. ‘You don’t want to see the chip pan coming through the window when you’re only out for a pound of mince!’ was his comment last week.

‘Animals.’ That’s what Frank called them. Things were better in his day, though. The Millars at 23 had got worse lately.

‘It’ll be herself rowing with the fancy man.’

Agnes reached for the telephone, pulled the chord to her, and when the receiver was within reach she placed her bony hand on it.

Shouting again. Screaming. The woman sounded hysterical now.

Agnes’s heart fluttered as she tightened her grip on the telephone. She lifted the receiver, made sure the line was working, and then lowered it again.

Everything went silent now. This was an unusual turn. Normally the rows went on for hours until there was some final act like a door slamming or a police car pulling up.

‘Oh, here we go.’

The door opened and a figure, pressed against the wall, eased silently into the night. Agnes squinted to see what was going on but there wasn’t enough light. The street lamps, smashed and never replaced, were no help in identifying the figure. She followed its stealthy trail into the shadows at the end of the road then returned her gaze to the house.

A woman, illuminated by the light from the hallway behind her, was sobbing on the front step. She was shaking; even at this distance that was visible. It was Sandra Millar, her face clearing into view every time she threw back her head.

‘He’ll have left her, that’ll be it.’

Agnes checked herself for sympathy – once she would have reached out, went over and offered to put the kettle on – but times had changed. These days you were more likely to be roared at, told not to interfere, and pointed back to your own door.

But Sandra Millar was truly in distress. The wailing and sobbing growing louder than it ever had before. Was she injured, in pain? The stories you heard these days, the things people did to each other. The old woman’s instincts begged her to get help.

‘Hello, police.’ She told the girl on the emergency line what she had just seen.

The operator recorded the details, was a kind enough sort. ‘There’ll be a patrol car around soon, just sit tight now.’

‘But what about herself? She’s in an awful state.’

‘I’d recommend you sit tight, just stay where you are until the police arrive.’

‘Right, OK.’

‘Would you like me to stay on the line with you?’

‘No, it’s all right.’ Her curiosity lingered.

‘Are you sure? Maybe just till the police get there.’

‘No, it’s fine. I’ll be fine.’

Agnes returned the telephone to its resting place and drew back the curtain once more, but as she saw Sandra holding her head in her hands she was compelled to go to her. She headed for the door and down the front steps, as she approached number 23 she heard low wails like a wounded animal. Agnes’s fluttering heart quickened, started to pound.

‘Hello, is everything all right?’

There was no answer. The sobbing stopped instantly. As the woman saw her neighbour’s approach, her mouth widened and her white face tightened in pain. She tried to scream, but the sound was trapped in her. She jolted upright and dashed into the house, heading for the kitchen. The door battered the wall, swung wildly, then she appeared again and bolted for the garden. She ran for the road and didn’t look back once.

Agnes’s breathing halted, she was cold. A chill breeze blew but that wasn’t the reason her temperature dropped. Beyond the doorway she peered into the fully-lit hallway and gathered her cardigan tight to her shoulders. The place was silent, appeared to be empty. She saw the wall-mounts with their smashed glass lying on the floor, and a smeared line, long and dark, running down the white wall towards the kitchen. She followed the smear-line like a pointer all the way to the next open door, to the sight of the kitchen table where he sat with a large wound above his shoulder blades and blood pooling on the well-worn linoleum beneath.

It took the old woman’s eyes a few moments to decipher the image in front of her and then the shock sent a shiver through her tensed body. Her knees loosened quickly as she fell into the open door, making a light thud as her delicate frame collapsed on the hard floor.

As Detective Inspector Bob Valentine left the station the red wash of sky was sinking into a jagged grey horizon. The King Street flats blocked most of the scene and allowed only a dim hum from the swelling traffic beyond. In the early evening, Ayr’s atmosphere pulsed with rushing commuters fleeing cramped offices. Previously sluggish limbs bursting with new energy. It was a time of day that never ceased to fascinate the detective, a strange place between the working world and the coming darkness that gave cover to a more sinister night.

Night crimes were always different from the affairs of daylight hours. If it sounded superstitious, supernatural even, then Valentine accepted it without a shrug. By this stage he knew the facts and they couldn’t be ignored, it would be a fool who tried. DI Bob Valentine knew he was no fool, at least when it came down to the job. In what remained of his life outside the force, he conceded, the opposite was likely to be true.

The silver Vectra was filthy, muddy arches and a roof covered in thick, mucky dust. The detective ran his finger along the dull wing and frowned. ‘Could write my name in that.’

He’d told DS McAlister to take the car for a wash and wax earlier but obviously he hadn’t barked loud enough for the importance of the request to register. ‘Bloody hell, Ally,’ he shook his head. ‘Tonight of all nights.’

Valentine opened the back door of the car and flung his briefcase in the footwell. As he removed his jacket a bead of sweat prickled on his brow, he dabbed at it with the back of his hand, settled behind the wheel and started the engine. The police radio was on, fizzed a little, then spluttered a message for uniform.

‘Getting reports of a disturbance on Arthur Street at the Meat Hangers nightclub, anyone available to attend?’

The detective leaned over and turned off the radio. The call was only a short diversion away, but it might as well have been a hundred miles.

‘No chance.’ He gripped the wheel.

It was a mild night, a slight breeze but nothing serious. One of those evenings where he was glad to be on the west coast; at the tail end of spring the west’s worst offence was mugginess blurring the views across the Firth of Clyde to the Isle of Arran. In the summer he’d heard you could grow tomatoes outside because of the warm winds of the Gulf Stream, though he had never tried. The idea of himself as a gardener was enough to make him laugh; days of domesticity, of normalcy, were not for him. He checked his wristwatch – at least he was on time – he might not arrive in a gleaming car but he’d arrive nonetheless. It would be a small victory to weigh against the deepening shame he had come to feel for his position as a family man who spent so little time at home.

Valentine drove to the edge of Barns Street and parked the car. The crimson sky was retreating behind a widening grey smear now, but it didn’t seem to bother the runners and dog walkers descending on the Low Green. In a few months the grass would be dotted with day-trippers clutching disposable barbecue sets and – the scourge of uniform – teenagers with two-litre bottles of cider. The detective drew a deep breath; his own daughter was just about old enough to be one of them. The thought that Chloe was of an age to experiment with drink, and more besides, made his insides tense.

The Vectra’s side-lights blinked as Valentine locked up and headed for the Gaiety Theatre. He checked his watch again, he was still on time, the idea that he wouldn’t be – after Chloe’s months of pestering – was unthinkable. Clare had already warned him about missing their daughter’s stage debut and Valentine regarded his daughter as too precious to disappoint. He made for the theatre, brushing the shoulders of his jacket with his fingertips as he went. Something like pride – he remembered it now – was sneaking back into his consciousness.