A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal (23 page)

Read A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal Online

Authors: Michael Preston Diana Preston

Tags: #History, #India, #Architecture

However, Shah Jahan’s own call to battle came quicker than he might have hoped or wanted. As one European visitor remarked of the Moghul Empire,

‘[the ruler] who without reluctancy submitted to the Moghul’s power while his camp was near immediately disclaims it when he knows the camp is at a distance, which commotions bring on the Moghul endless trouble and expense’

. This time the source of the trouble was, once more, the wealthy, disaffected sultans of the Deccan. In late 1629, Shah Jahan prepared to march south with his armies. Mumtaz, well advanced in her thirteenth pregnancy, was as usual to accompany her husband. She would not see Agra, or her newly sown terraced gardens just sprouting into life on the banks of the Jumna, again.

*

Mumtaz’s riverside garden, today known as the Zahara Bagh, lies to the south of the Ram Bagh, a garden once cultivated by her aunt Nur.

*

Asaf Khan’s beautiful mansion was apparently blown up by the British after the 1857 sepoy revolt, when they were anxious to clear their lines of fire for any future engagement.

*

An exception is the white marble tomb of Hoshang Shah, the Muslim ruler of the fortress city of Mandu, built in 1440.

*

Shah Jahan may also have had a hand in the construction of his father’s tomb.

†

The most important official chroniclers of Shah Jahan’s reign were Mirza Amina Qazwini, who wrote the fullest account of Shah Jahan’s princehood; Abdul Hamid Lahori, who wrote the detailed account of the first twenty-six years of Shah Jahan’s reign, the

Padshahnama

; Muhammad Waris, Lahori’s pupil, who extended Lahori’s account up to and including the thirtieth year of Shah Jahan’s reign; and Inayat Khan, keeper of Shah Jahan’s library, whose work effectively summarizes that of his predecessors. Muhammad Salih Kambo, although not an official court historian, was a member of the court records department and wrote a detailed account of Shah Jahan’s reign using the official histories as a base and adding his own recollections while taking the reign through to its close.

*

The emerald, the oldest known true gemstone, is especially prized by Muslims, who consider green the colour of Islam. Furthermore, the emerald has long been venerated in India for its religious and astrological significance. It was first found in Egypt almost 5,000 years ago and the Romans plundered Cleopatra’s mines for it. By Shah Jahan’s time emeralds also came from South America.

*

Khichari

was the origin of the popular Anglo-Indian dish kedgeree, which, with its ingredients of hard boiled eggs and smoked fish, departed significantly from the original.

*

A recent DNA study found that all the world’s cultivated potatoes derive from a single species native to southern Peru.

*

Karim’s Restaurant in the teeming streets of Old Delhi is run by descendants of chefs of the Moghul court who claim that ‘cooking royal food is our hereditary profession’.

*

Moghul beauty aids were more appealing than contemporaneous European ones that had women mixing cat dung with urine to remove unwanted hair and fashioning false eyebrows from mouse skins.

8

‘Build for Me a Mausoleum’

A

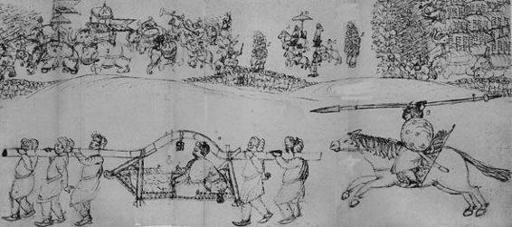

Moghul army on the move was, in the words of English clerk Peter Mundy, ‘a most majestical, warlike and delightsome sight’, as it was no doubt intended to be. It would certainly have appealed to movie moguls in later times.

*

First to appear was the artillery, the cannons pulled on wooden gun carriages. Some, like the one on which Shah Jahan bestowed the name ‘World Conqueror’, had barrels as long as seventeen feet. The enormous baggage train followed with its mass of pack elephants, ‘like a fleet of ships’ in a sea of dust, its ranks of spitting camels and patient mules and its thousands of ox-drawn carts. Labourers with spades and pickaxes on their shoulders marched with the baggage train, ready to clear obstacles from the path.

The awesome pageantry was born of much practice – Moghul emperors spent at least a third of their reigns on the move, going from camp to camp either on campaign or on tours of inspection of an empire that, according to Abul Fazl, took a year to traverse. The appurtenances of government accompanied the emperor, from his throne and the imperial records and accounts – so massive that they required numerous wagons to carry them – to sacks of gold coin, silken robes of honour and bejewelled swords to be presented as gifts. As a Moghul general reflected,

‘If the treasury is with the army, the merchants following the army [to supply it] have a sense of security too.’

Sometimes the emperor would pause on the march for a snack and everything had to be ready to anticipate his wishes. The royal kitchens therefore moved en masse with the emperor, the imperial gold and silverware and porcelain wrapped and stowed in panniers, and supplies of food and water for the imperial family carefully guarded for fear of poisoners. Tandoors – the hot clay ovens used by the Moghuls in their nomadic days and introduced by them into India – were an efficient means of cooking food quickly on the move, especially meat, lentils and bread.

*

Shah Jahan sometimes rode, protected from the sun by a silken parasol, on fine horses kept in peak condition by a special diet that included butter and sugar. When he tired of riding, he would mount his own imperial elephant,

‘richer adorned than the rest’

, and sit beneath a canopy of cloth of gold. To awestruck foreigners, this was

‘by far the most striking and splendid style of travelling, as nothing can surpass the richness and magnificence of the harness and trappings’. Alternatively, he was borne along in a ‘field throne … a species of magnificent tabernacle, with painted and gilt pillars and glass windows … the four poles of this litter are covered either with scarlet or brocade, and decorated with deep fringes of silk and gold. At the end of each pole are stationed two strong and handsomely dressed men, who are relieved by eight other men constantly in attendance.’

Moghul noblewomen sometimes rode on horseback, especially in mountainous regions, concealed from public view by a linen garment covering them from head to toe, with only a small, letterbox-shaped piece of netting to look through. More usually, hidden behind brocade or satin curtains, they reclined full-length in palanquins suspended from curved bamboo poles resting on the shoulders of four or six bearers trained to run smoothly over uneven ground and thus avoid jolting the dozing occupant. Bent bamboos were specially cultivated at great expense for the purpose. Women could also lie in sumptuously upholstered ox-drawn carts or in capacious litters slung between two powerful camels or two small elephants. Peter Mundy described how the litter’s sides were covered with

‘a certain hard, sweet smelling grass … just like our thatch in England, making fast therein a little earth and barley, so that throwing water on the outside, it causes the inside to be very cool … and also in a few days causes the barley to spring out, pleasant to see …’

The Moghul court on the move, drawn by Peter Mundy

.

Mumtaz and her daughters travelled in yet greater luxury and dignity, as befitted their rank. Sometimes they were carried on men’s shoulders in roofed and gilded litters resembling sedan chairs and

‘covered with magnificent silk nets of many colours, enriched with embroidery, fringes, and beautiful tassels’

. Often they rode in richly decorated howdahs – small, swaying, glittering canopied castles – secured to the backs of docile female elephants by means of pulleys and ropes. Through screens of golden mesh the empress could look out on the passing world, thanks to the practice of sprinkling water on the road ahead to subdue the dust that would otherwise have risen in choking clouds around her.

Strict protocol was preserved throughout. When Mumtaz wished to travel by elephant, the beast was led into a specially erected tent, where it knelt down. The mahout, or elephant driver, covered his head with a piece of coarse cloth to ensure he caught no glimpse of his royal passenger as she climbed into her howdah. She seldom travelled with Shah Jahan. Instead the imperial harem followed about a mile behind, surrounded closely by armed female guards and by eunuchs who drove off flies with jewelled peacock-feather fans.