A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal (44 page)

Read A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal Online

Authors: Michael Preston Diana Preston

Tags: #History, #India, #Architecture

The corridor and subterranean chambers are clearly contemporary with the rest of the building. When Shah Jahan visited the Taj Mahal he did so by river. (The Archaeological Survey of India identified in 1958 the remains of a platform that would have supported the jetty.) Although some argue that the arched chambers were never more than part of the architects’ sophisticated system to spread the load of the heavy structure above, the consensus is that, when the Taj Mahal was originally built, the arches on the river side of the main subterranean chambers were open and thus that the seventeen chambers provided a series of verandas for the emperor to walk along as he made his way from the jetty to his wife’s grave. He could have looked out from the verandas’ shade across the river to the Mahtab Gardens. The reason why the verandas were bricked in could have been as a precaution against flooding or, more likely, as part of work commissioned by Shah Jahan in 1652 to repair the dome of the mausoleum and to strengthen the Taj Mahal’s structure, following Aurangzeb’s report of cracks and leaks.

However, the purpose of the corridor is not so clear. Some archaeologists have argued that it originally ran around all four sides of the foundations of the marble plinth and that at some point it gave access to a crypt beneath the existing one in which there would have been a third set of graves, the real ones. In support of this theory they quote the fact that the corridor is some nine feet longer than the marble plinth, which would allow for four-foot-wide corridors to run off from it at both ends around the foundations. They refer to what seem to be filled-in doorways at each end of the corridor where it might be assumed to have once turned at right angles around the plinth. The disputed nineteenth-century documents reputedly copied from earlier lost manuscripts speak of the cost of three sets of tombstones. Even if these documents represent only a nineteenth-century setting down of oral tradition, it seems a little odd that such a tradition should support the existence of a third pair of tombs if they did not exist. (The reason for blocking access to them could have been to preserve structural integrity during repairs in 1652, or at a later stage to prevent vandalism or looting when the Moghuls’ hold on Agra began to slip.) However, a definitive view would require further archaeological investigations and the Archaeological Survey of India say they have no intention to undertake them at present.

Controversy about whether the Taj Mahal was originally a Hindu temple rumbles on. Arguments about the comparative achievements of Hindu and Muslim in the architecture of India are not new and have often detracted from an assessment of what the Taj is – a synthesis of the two traditions. For example, Aldous Huxley in the 1920s wrote:

‘The Hindu architects produced buildings incomparably more rich and interesting as works of art [than] the Taj Mahal.’

However, in recent decades, some non-mainstream Hindu historians have given such controversies a new twist, suggesting that Shah Jahan did not create the Taj Mahal from nothing; rather, he modified a pre-existing building – either a Rajput palace or a Hindu temple – built by the Raja of Amber (Jaipur).

The claim of these historians, which seemingly seeks to minimize the Moghul contribution to Indian architecture (some have also questioned whether other buildings such as Humayun’s tomb were Moghul constructions), has received no support from academic historians of any background and there is no evidence from contemporary Rajput, Moghul or European sources to justify it. The claim is based around statements by two of the official contemporary chroniclers of Shah Jahan that there was, or had been, a much earlier palace on the site of the Taj Mahal, which the Raja of Amber gave to the emperor and for which he was, in turn, rewarded with four other estates. It is this building that the dissenting historians suggest Shah Jahan modified, leaving clear traces of Hindu architectural features. Over time, under the pressure of debate the Hindu writers’ description of the original building has varied from that of a palace to a Shiva temple whose name ‘Tajo-Mahalaya’ produced the name Taj Mahal. They have also suggested that the reason for the bricking-up of the subterranean corridors of the Taj Mahal was that they gave access to a statue of Shiva.

The strong counter-arguments are that all accounts of the construction of the tomb, whether by court historians or by European observers such as Peter Mundy who were present when building started, make clear that work started from the foundations up. The chronicler Lahori talked of

‘laying the foundations’ by digging down to ‘the water table’

. Peter Mundy noted that

‘the building is begun …’

If there had been any previous major structure on the site, other observers who had visited Agra before Mumtaz’s death would have recorded it. There would have been no reason for Babur not to have mentioned it when he first came to Agra and was so disappointed with his surroundings. (He could not have known that over a hundred years later his descendants would turn it into a tomb and claim that they had built it from scratch.) Similarly, Europeans such as the Jesuit Father Monserrate, who visited Agra several times in 1580 to 1582, or Sir Thomas Roe, who gave such a detailed description of Agra and court life in the early seventeenth century, and Pelsaert, the Dutch trader who visited Agra in 1620 to 1627 and enumerates the gardens and palaces along the Jumna, make no mention of any pre-existing building. Although the royal archives of the Raja of Amber, who donated the land for the building, refer to building projects – including temples – elsewhere, they contain no reference to any such construction in Agra. Furthermore, the Hindu architectural features of the Taj, such as the

chattris

, are more likely to derive from the synthesis of Hindu and Islamic styles so apparent in Moghul architecture from Akbar’s time onwards.

The claim that the building was a Shiva temple particularly puzzles Indian scholars, both because temples cannot be sold after construction and Shah Jahan would not have committed such an inauspicious act as seizing the land, and because the Rajas of Amber belong to a particular branch of the Hindu religion who would not have worshipped at a Shiva temple. Perhaps even more conclusively, no known Hindu temple looks at all like the Taj Mahal.

Coming from the other side of the religious divide, the Wakf Board, a charitable endowment set up after the partition of India in 1947 to look after deserted Muslim graves, recently tried to claim guardianship of the Taj Mahal so that they could manage it within the stricter religious guidelines of Sharia law. In late 2005 the Indian Supreme Court dismissed their case on the grounds that the Taj Mahal had in both Moghul and British times been considered the property of the Crown or State and that legally it had remained national property on the transfer of power to independent India.

Such partisan arguments and controversies will no doubt persist, just as the Taj will remain for everyone what Bernier called it some 350 years ago – ‘a wonder of the world’ – even though the original vision in the mind of Shah Jahan will always be slightly mysterious.

*

Champa flowers are used as votive offerings in Hindu temples and can also be distilled into fragrant hair oil still used by Indian women.

†

The Mahtab Bagh is today open to the public after being restored. The beds are again filled with flowers, attracting hundreds of bees and butterflies. The ASI have planted over 10,000 plants and shrubs, including the cockscomb, the mango and the lushly scented champa.

*

Among those who consider that it was Shah Jahan’s intention to be interred in the Mahtab Bagh is Professor R. C. Agrawal, current Joint Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India.

Postscript

R

esearch for this book took us to many places, from panelled Oxford libraries to the china delicacy of the mosques of Isfahan, the shifting, sandy banks of the meandering Oxus in Uzbekistan and, of course, to India. Here we retraced the lives of Shah Jahan and Mumtaz from the ruins of the palace of Burhanpur, where Mumtaz died, to the Taj Mahal itself. Though we had visited the Taj many times in the past, finding it each time faultlessly and enduringly lovely, this time we wondered whether our newly acquired knowledge might in some way diminish it for us. We need not have worried. The Taj Mahal transcended any recollections, any scrutiny of plans, any detailed computation of symmetry, any overheated metaphors with which we had grappled. As we approached, the sudden appearance of the ethereal white mausoleum, framed mirage-like in the solid red sandstone arch of the gatehouse, again made us pause and catch our breath.

Edward VII, who visited India when he was Prince of Wales in 1875, observed wearily that it had become commonplace for every writer who visited the Taj

‘to set out with the admission that it is indescribable and then to proceed to give some idea of it’

. Even if one agrees with Shakespeare that

beauty itself doth of itself persuade

the eyes of men without an orator

and sympathizes with the view that beauty is so subjective, so intuitive, so much in the eye of the beholder, that what makes something beautiful is that someone thinks it is, it is indeed irresistible to pick out some of the elements that have made so many people from all over the world, all cultures, and both sexes, think the Taj Mahal is beautiful.

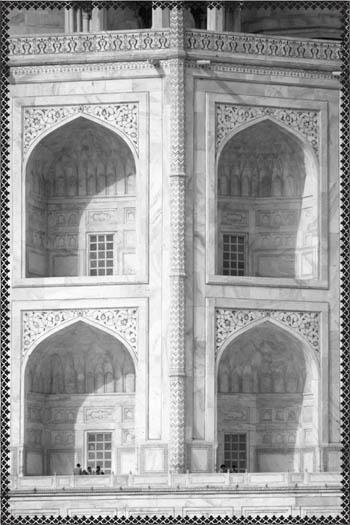

Most of us find symmetry and structure inherently appealing. When researchers showed people two pictures of the same person – one of the real face with the natural asymmetries common to us all and the other artificially composed of half of their face and its mirror image, thus producing greater symmetry – by far the majority preferred the symmetrical version. In appreciating music and other arts, structure seems required for beauty although the former does not guarantee the latter. So it was for us with the Taj Mahal, whose symmetry and structural coherence we found deeply satisfying. We appreciated the way in which, as we walked towards the mausoleum, the shapes and architectural features rose in an almost hierarchical ascent of ever-greater delicacy and definition.

Unlike other Islamic or Moghul buildings we had seen in India, the Taj not only juxtaposes elements from Islamic and Hindu traditions but synthesizes and subtly modifies them to produce a building that is much greater than the sum of its influences. We found the complex more fluid, more empathetic, more human than much Islamic architecture, simpler and more clearly structured than some Hindu buildings. We were struck by the combination of grand scale and attention to detail. The nineteenth-century Bishop Heber caught this feeling perfectly when he described the Taj Mahal as having been built by giants and finished by jewellers.

At just the time that the Taj Mahal was being built, the Reverend Thomas Fuller, an essayist as well as cleric, wrote that

‘light (God’s eldest daughter) is a principal beauty in building’

. We felt this was overwhelmingly true of both the interior and exterior of the Taj Mahal. The change of light within the building throws into greater relief the incised carving and, as it strengthens or softens as the day progresses, changes the mood. Outside, the Taj benefits from still having the sky as its only backcloth, as Shah Jahan planned. There is no competition or distraction from other buildings or even trees. The sunlight on the water of the pools and channels reflects the building; shadows increase and decrease the depth of the

iwans

, or recesses, as the hours pass. The receptivity of the Makrana marble to the changing light and atmosphere produces shades of colour and mood.