A Wedding in Haiti (21 page)

Read A Wedding in Haiti Online

Authors: Julia Alvarez

Eseline pulls her mother-in-law by the hand toward the path to meet us. But Piti’s mother is holding back, pointing to her dirty dress, her muddy bare feet. Later, she will explain to Piti that she was all set to receive us early this morning. But when we didn’t appear, she figured we had changed our plans. Besides, she had work to do.

Well, two mountains cannot meet, but two people can. Bill and I trek into the field to greet her. She grabs each of us in turn, rocking us in her arms, as if we, too, are her children who have come home.

Mama Piti joins us on the path, drawn by the bait of her little granddaughter asleep in her father’s arms. Piti lifts the facecloth draped over Ludy’s face to keep the sun from her eyes. Mama Piti has been grinning since we met her, lips pressed together, as if trying to suppress a smile. But now, she lets loose and smiles widely. I see what she’s been hiding: her front teeth are missing.

We walk down toward the house, the path too narrow for keeping our arms around each other, though we keep trying. In the hollow sits the small house, the metal roof rusted, the mud walls cracked and crumbling in patches—the house of an old woman whose children have grown up and moved away. In fact, four of her five sons have gone to work in la République. In a plaintive moment, she asks me something that at first Piti is reluctant to translate. “Why have you taken all my sons?”

Mama Piti disappears inside her house. I assume she’s getting us some coffee or some chairs to sit on. But as we tour her garden with Piti, we find her in the backyard just finishing up washing her feet and changing into her company outfit: a faded red-and-white print dress with a black belt. Her straw hat is gone, and instead she has donned a fresh kerchief tied around her head.

We stand around for a while—chairs seem scarce here—watching Ludy and her grandmother get acquainted. It’s hard to visit when you don’t share a language. Piti translates into Kreyòl, then back to Spanish, then to Kreyòl again. At one point, I ask for his mother’s name so as not to keep referring to her as Mama Piti. Infancia, a funny name for an old lady, Infancy. As for her age, she is not sure. Maybe she is seventy? Her response is a question, as if her age were up to us to determine.

It occurs to me that in our excitement to get going, we forgot his mother’s pile of staples back at Charlie’s house! Piti translates for his mother—her gifts are coming later: rice and beans and sugar, cans of tomato paste and sardines, boxes of chocolate and spaghetti. Infancia smiles widely. There have to be some perks to having sons working in la République.

It’s closing in on noon, and we still have the longer outing to Eseline’s family to deliver her and the baby. Infancia walks us back to the truck. As we say our farewells, I can’t help feeling that, while I’m not responsible for all her sons, I am accountable for one of them being gone. I know no way to make it up to Infancia except to promise that I will take care of her son. Piti translates my words. I look in her eyes, trying to say what can’t be put into words, even if we did speak the same language.

She gazes back at me. Her eyes are her son’s eyes, which I’ll get to see much more often than she will.

The great problems of the world

We wolf down lunch—our standard quick meal on this trip:

casave

and cheese, and whatever fruit is on hand—then pile up the gifts in the back. It would be a heavy load to try to carry to Eseline’s house. But Piti assures us that Eseline’s family has been forewarned and will be waiting for us on the road with their donkey.

We are all feeling excited for Eseline, reuniting with her family after almost a year away. But also for Charlie, who’ll be making a formal petition to Rozla’s parents to marry their daughter. I’d be sweating bullets, but Charlie looks his usual unflappable self, in his yellow polo shirt and reflector sunglasses. Although it has been a long time since I was that young, I have to confess that every time I’m around him, I feel like I’m back in high school. Charlie is the kind of totally cool guy who was nice to everyone, but we all knew we were way over our heads in his presence. I don’t know what the equivalent is in Moustique, but I can’t imagine that Rozla’s parents will find fault with him.

Actually, come to think of it, those cool high school studs were precisely the guys our parents did not want us to date. Charlie’s coolness could work against him. By Eseline’s own admission, her father is not easy. With six daughters, and only one son, Papa keeps a tight rein. Look at the hard time he gave Piti because the poor guy couldn’t come up with a pair of earrings! If Eseline’s father found fault with Piti, he’ll find fault with anybody. Charlie might well be sent packing.

I wish I had the familiarity with Charlie that I have with Piti, so I could give him a little coaching. The reflector glasses should go. The kerchief he likes to tie like an ascot around his neck—it sends the wrong message. The kind of thing that might fly in a resort in the Bahamas, but not with Papa Eseline, who is, after all, a dirt farmer, a man who wore his work clothes to his daughter’s wedding.

But I’m not that close to Charlie, and besides, who knows how the marriage brokerage system works here. What asset trumps what flaw. Rozla’s parents might well be impressed by Charlie’s credentials: his work sojourns in the Bahamas and in the Dominican Republic. His nice house with a concrete foundation and a zinc roof. His little English and Spanish. What I can do is put in my two cents whenever I get the chance. Using my minimal French and my increasingly evolving mime skills, I’ll let Eseline’s parents know that Charlie

est très bon, très intelligent, très très magnifique.

Haiti has brought out the Yenta in me.

Piti had told his in-laws that we would be at the spot where the path meets the road at noon. But it’s past one o’clock by the time we pull over. We’re happy to see that the welcome committee has not given up: three of Eseline’s sisters and a tiny donkey are waiting for us. Eseline throws open the back door before the pickup has stopped moving and jumps out to greet them. The sisters all hug each other, exclaiming and giggling, like a bunch of cheerleaders. My heart feels as if it has sprouted wings, beating at the doors of my rib cage, wanting to soar above this happy scene. I make the mistake of looking up, only to see thunderclouds moving across the sky toward us. I remember the deal I made last night and shudder.

Once we start unloading the back of the pickup, I’m thinking, no way that poor donkey can carry all this stuff in its two saddlebags. The older of the three waiting sisters, Lanessa, takes charge. She is a tall, slender girl in her teens, the daughter who comes after Rozla. Lanessa begins loading the saddlebags until they are stuffed. The poor donkey grunts under the weight of it all. At moments like this I find myself revisiting the idea of reincarnation. What brutish dictator, or cruel warrior, has come back to pay his dues?

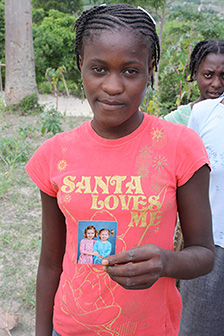

Lanessa finally loops the rope around the top of the load and around the donkey’s middle and pulls tight, leaning back on her heels. The donkey rocks as if it is going to fall over. Finally, the load secured, we are on our way, Lanessa leading the donkey, rope in hand, gifts piled high. Her red T-shirt reads

SANTA LOVES ME

. Today, it seems, he does.

We climb up and down hill, single file on the narrow path, a reminder of last year’s journey: the wedding party accompanying the young bride, who was departing for what must have seemed a far-off land. Now we are bringing her back.

As we clear the top of another hill, the donkey starts trotting, and Eseline picks up her steps. Sure enough, there below is her parents’ house in the clearing. A bunch of little girls and one lone boy race uphill to meet us. Behind them, an older woman—probably all of forty or younger—throws her arms out in joyous welcome. There are howls of happiness as mother and daughter fall into each other’s embrace.

The baby gets handed around. Ludy has got to be what I call a “Buddha baby”: taking in all the excitement with a bemused expression. Ho-hum, another day in the human race. She is carried away by three of Eseline’s little sisters, who range in age from eight to eleven, still at the stage to be playing with dolls. But the little sisters don’t confine themselves to one small doll. They’ve also taken Mikaela with them, down a path to the other houses that surround this one. “What were they up to?” I ask later when she has been returned.

Mikaela herself isn’t sure. “They took me from house to house and showed me to their families. They also wanted to play with my hair.” A petite young woman with a head of curls and blue eyes—dolls don’t get any prettier.

Later, when asked about my family, I’ll pull out a wallet photo of my own two pretty, blonde-haired granddaughters. Lanessa takes the photo in her two hands, poring over it. She says something to Piti, who translates. “Can she please, please have it to keep?” I feel a little disconcerted. Lanessa doesn’t even know who these girls are! But owning their picture is a way of having them, at least to look at. I let her keep it. I have plenty more where that came from.

While the little girls are off playing dolls with Ludy and Mikaela, Bill and I are led by the hand under the awning and sat down on two cane chairs like older dolls ourselves. Piti and Eseline chatter away with her parents, while Bill and I look on, pleased to see them all so happy.

Periodically, Eseline’s mother turns to me and utters an exclamation with lifted arms in the manner of a believer at a tent revival. I start to get the feeling I should respond in kind. “We love Piti, we love Eseline, and Ludy—” Loude Sendjika, I have to remember to call her here. And while I’m at it: “We love Charlie. Charlie

, c’est un bon homme.

” Bill flashes me a look.

Hold the gush, before you ruin everything

. Charlie hasn’t spoken up yet, and the parents might get upset at a romance begun without their blessing.