A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future (11 page)

Read A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future Online

Authors: Daniel H. Pink

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Leadership, #Self-Help, #Personal Growth, #Success

Some pundits might write off these developments as mass manipulation by wily marketers or further proof that well-off Westerners are mesmerized by style over substance. But that view misreads economic reality and human aspiration. Ponder that humble toaster. The typical person uses a toaster at most 15 minutes per day. The remaining 1,425 minutes of the day the toaster is on display. In other words, 1 percent of the toaster’s time is devoted to utility, while 99 percent is devoted to significance. Why

shouldn’t

it be beautiful, especially when you can buy a good-looking one for less than forty bucks? Ralph Waldo Emerson said that if you built a better mousetrap, the world would beat a path to your door. But in an age of abundance, nobody will come knocking unless your better mousetrap also appeals to the right side of the brain.

Design has also become an essential aptitude because of the quickened metabolism of commerce. Today’s products make the journey from L-Directed utility to R-Directed significance in the blink of an eye. Think about cell phones. In less than a decade, they’ve gone from being a luxury for some to being a necessity for most to becoming an accessorized expression of individuality for many. They’ve morphed from “logical devices” (which emphasize speed and specialized function) to “emotional devices” (which are “expressive, customizable, and fanciful”), as Japanese personal electronics executive Toshiro Iizuka puts it.

14

Consumers now spend nearly as much on decorative (and nonfunctional) faceplates for their cell phones as they do on the phones themselves. Last year, they purchased about $4 billion worth of ring tones.

15

Indeed, one of design’s most potent economic effects is this very capacity to create new markets—whether for ring tones, cutensils, photovoltaic cells, or medical devices. The forces of Abundance, Asia, and Automation turn goods and services into commodities so quickly that the only way to survive is by constantly developing new innovations, inventing new categories, and (in Paola Antonelli’s lovely phrase) giving the world something it didn’t know it was missing.

Designing Our Future

Design can do more than supply our kitchens with cooking implements that stir both our sauces and our souls. Good design can change the world. (And so, alas, can bad design.)

“It’s not true that what is useful is beautiful. It is what is beautiful that is useful. Beauty can improve people’s way of life and thinking.”

—

ANNA CASTELLI FERRIERI,

furniture designer

Take health care. Most hospitals and doctors’ offices are not exactly repositories of charm and good taste. And while physicians and administrators might favor changing that state of affairs, they generally consider it secondary to the more pressing matters of prescribing drugs and performing surgery. But a growing body of evidence is showing that improving the design of medical settings helps patients get better faster. For example, in a study at Pittsburgh’s Montefiore Hospital, surgery patients in rooms with ample natural light required less pain medication, and their drug costs were 21 percent lower, than their counterparts in traditional rooms.

16

Another study compared two groups of patients who suffered identical ailments. One group was treated in a dreary conventional ward of the hospital. The other was treated in a modern, sunlit, visually appealing ward. Patients in the better-designed ward needed less pain medicine than those in the less inviting ward and were discharged on average nearly two days early. Many hospitals are now redesigning their facilities to include greater amounts of natural light, waiting rooms that provide both privacy and comfort, and an array of design features such as meditative gardens and labyrinths that physicians now realize can speed the healing process.

Similar potential exists in bringing a new design sensibility to two other settings where beauty has long taken a backseat to bureaucracy—public schools and public housing. A study at Georgetown University found that even if the students, teachers, and educational approach remained the same, improving a school’s physical environment could increase test scores by as much as 11 percent.

17

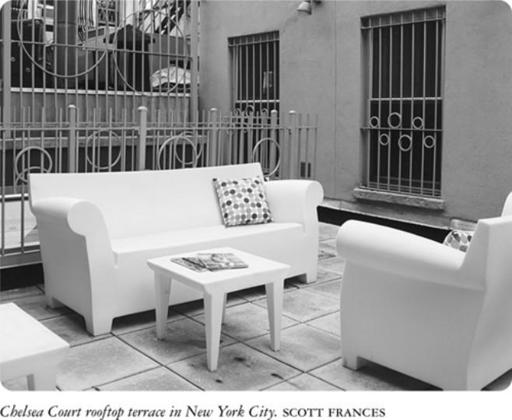

Meanwhile, public housing, notorious for its abominable aesthetics, may be in the very early stages of a renaissance. A nice example is architect Louise Braverman’s Chelsea Court in New York City. Constructed on an austere budget, the building has colorful stairwells, airy apartments, and a roof deck with Philippe Starck furniture—all for tenants who are low-income or (formerly) homeless.

Design can also deliver environmental benefits. The “green design” movement is incorporating the principles of sustainability in the design of consumer goods. This approach not only creates products from recycled materials but also designs the products with aneye to their eventual disposal as well as their use. Architecture is likewise going green—in part because architects and designers are understanding that in the United States, buildings generate as much pollution as autos and factories combined. More than 1,100 buildings in the United States have applied to the U.S. Green Building Council to be certified as environmentally friendly.

18

If you’re still unconvinced that design can have consequences beyond the carport and cutting board, point your memory back to the 2000 U.S. presidential elections and the thirty-six-day snarl over whether Al Gore or George W. Bush won the most votes in Florida. That election and its aftermath may seem like a bad dream today. But buried in that brouhaha was an important, and mostly ignored, lesson. Democrats alleged that the U.S. Supreme Court, by halting the recount of ballots, handed the election to George W. Bush. Republicans claimed that their opponents tried to steal the election by urging voting officials to count chads—those little rectangular ballot pieces—that were not fully punched out. But the truth is that both sides are wrong.

According to an exhaustive examination of all of Florida’s ballots that several newspapers and academics conducted a year after the election—and whose findings were largely lost amid the coverage of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and utterly forgotten after Bush’s 2004 reelection—what determined who won the U.S. presidency in 2000 was this:

This is the infamous butterfly ballot that voters in Palm Beach County used to mark their choice for President. In Palm Beach County—a heavily Democratic enclave populated by tens of thousands of elderly Jewish voters—ultraconservative fringe candidate Pat Buchanan received 3,407 votes, three times as many votes as he did in any other county in the state. (According to one statistical analysis, if the voting pattern of the state’s other sixty-six counties had held in Palm Beach, Buchanan would have won only 603 votes.)

19

What’s more, 5,237 Palm Beach County voters marked ballots for

both

Al Gore and Pat Buchanan, and therefore had their ballots invalidated. Bush carried the entire state by 537 votes.

What explained Buchanan’s stunning performance and the thousands of invalidated ballots?

Bad design.

The nonpartisan investigation found that what decided the outcome in Palm Beach County—and therefore determined who would become leader of the free world—wasn’t an evil Supreme Court or recalcitrant chads.

It was bad design.

The bewildering butterfly ballot confused thousands of voters and cost Gore the presidency, according to the professor who headed the project. “Voters’ confusion with ballot instruction and design and voting machines appears to have changed the course of U.S. history.”

20

Had Palm Beach County had a few artists in the room when it was designing its ballot, the course of U.S. history would likely have been different.

*

Now, intelligent people can argue whether the butterfly ballot and the confusion it wrought ultimately produced a good or bad result for the country. And this isn’t partisan sniping from somebody—full disclosure—who worked for Al Gore ten years ago and who remains a registered Democrat. Bad design could have worked to Democrats’ advantage and the Republicans’ chagrin—and one day it likely will. But whatever our own partisan persuasion, we should consider the butterfly ballot the Conceptual Age equivalent of the Sputnik launch. It was a surprising, world-changing event that revealed how weak Americans were in what we’d now discovered was a fundamentally important strength—design.

D

ESIGN IS

a high-concept aptitude that is difficult to outsource or automate—and that increasingly confers a competitive advantage in business. Good design, now more accessible and affordable than ever, also offers us a chance to bring pleasure, meaning, and beauty to our lives. But most important, cultivating a design sensibility can make our small planet a better place for us all. “To be a designer is to be an agent of change,” says CHAD’s Barbara Chandler Allen. “Think of how much better the world is going to be when CHAD kids pour into the world.”

*The correct answers are: 1-b, 2-c, 3-a

*Less well known is the ballot in Duval County in which the presidential ballot showed five candidates on one page and another five candidates on the next page, along with instructions to “vote every page.” In that county, 7,162 Gore ballots were tossed out because voters selected two candidates for President. Had the instructions been clearer, Duval County, too, would have provided Gore the margin of victory.

Keep a Design Notebook.

Buy a small notebook and begin carrying it with you wherever you go. When you see great design, make a note of it. (Example: my $6.95 Hotspot silicone trivet—a thin, flexible square that doubles as a pot holder, triples as a jar opener, and looks cool.) Do the same for flawed design. (Example: the hazard light button in my car, which is so close to the gearshift that I often turn on the hazards when I put the car in PARK.) Before long, you’ll be looking at graphics, interiors, environments, and much more with greater acuity. And you’ll understand in a deeper way how design decisions shape our everyday lives. Be sure to include the design of experiences as well—buying a cup of coffee, taking a trip on an airplane, going to an emergency room. If you’re not a note-taker, carry around a small digital camera or camera cell phone instead and snap photos of good and bad design.

Channel Your Annoyance.

1. Choose a household item that annoys you in any way.

2. Go by yourself to a café with pen and paper, but without a book and without a newspaper, and, for the duration of your cup of coffee, think about improving the poorly designed item.

3. Send the idea/sketch as it is to the manufacturer of your annoying household item.

You never know what might come of it.

The above from Stefan Sagmeister, graphic design impresario. (More info:

www.sagmeister.com

)