A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future (5 page)

Read A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future Online

Authors: Daniel H. Pink

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Leadership, #Self-Help, #Personal Growth, #Success

This arrangement has been a rousing success. It has broken the stranglehold of aristocratic privilege and opened educational and professional opportunities to a diverse set of people. It has propelled the world economy and lifted living standards. But the SAT-ocracy is now in its dying days. The L-Directed Thinking it nurtures and rewards still matters, of course. But it’s no longer enough. Today, we’re moving into an era in which

R-Directed Thinking

will increasingly determine who gets ahead.

To some of you, this is delightful news. To others, it sounds like a crock. This chapter is mainly for the latter group of readers—those who followed your parents’ advice and scored well on those aptitude tests. To persuade you that what I’m saying is sound, let me explain the reasons for this shift using the left-brain, mechanistic language of cause and effect. The effect: the diminished relative importance of L-Directed Thinking and the corresponding increased importance of R-Directed Thinking. The causes: Abundance, Asia, and Automation.

Abundance

Another vignette from the 1970s: every August my mother would take my brother, sister, and me to buy clothes for the new school year. That inevitably meant a trip to Eastland Mall, one of three big shopping centers in central Ohio. Inside the mall we’d visit a national department store such as Sears or JCPenney or a local one such as Lazarus, where the children’s departments featured maybe a dozen racks of clothing from which to choose. The rest of the mall consisted of about thirty other stores, smaller in size and selection, lined up between the department store anchors. Like most Americans of the time, we considered Eastland and those other climate-controlled enclosed shopping centers the very zenith of modern plenty.

My own kids would consider it underwhelming. Within a twenty-minute drive of our home in Washington, D.C., are about forty different mega-shopping sites—the size, selection, and scope of which didn’t exist thirty years ago. Take Potomac Yards, which sits on Route 1 in northern Virginia. One Saturday morning in August, my wife and I and our three children drove there for our own back-to-school shopping excursion. We began at the giant store on the far end of the site. In the women’s section of that store, we chose from Mossimo designer tops and sweaters, Merona blazers, Isaac Mizrahi jackets, and Liz Lange designer maternity wear. The kids’ clothing section was equally vast and almost as hip. The Italian designer Mossimo had a full line of children’s wear—including a velour pants and jacket set for our two girls. The choices were preposterously more interesting, more attractive, and more bountiful than the clothing I chose from back in the seventies. But there was something even more noteworthy about this stylish kiddie garb when I compared it to the more pedestrian fashions of my youth: the clothes cost less. Because we weren’t at some swank boutique. My family and I were shopping at Target. That velour Mossimo ensemble? $14.99. Those women’s designer tops? $9.99. My wife’s new suede Isaac Mizrahi jacket? Forty-nine bucks. A few aisles away were home furnishings, created by designer Todd Oldham and less expensive than what my parents used to pick up at Sears. Throughout the store were acres of good-looking, low-cost merchandise.

And Target was just one of an array of Potomac Yards stores catering to a mostly middle-class clientele. Next door we could visit Staples, a 20,000-square-foot box selling 7,500 different school and office supplies. (There are more than 1,500 Staples stores like it in the United States and Europe.) Next to Staples was the equally cavernous PetSmart, one of more than six hundred such pet supply stores in the United States and Canada, each one of which, on an average day, sells $15,000 worth of merchandise for nonhumans.

2

This particular outlet even had its own pet-grooming studio. Next to PetSmart was Best Buy, an electronics emporium with a retail floor that’s larger than the entire block on which my family lives. One section was devoted to home theater equipment, which displayed an arms race of televisions—plasma, high-definition, flat panel—that began with a 42-inch screen and escalated to 47-inch, 50-inch, 54-inch, 56-inch, and 65-inch versions. In the telephone section were, by my count, 39 different varieties of cordless phones. And these four stores constituted only about one-third of the entire shopping facility.

But what’s so remarkable about Potomac Yards is how utterly unremarkable it is. You can find a similar swath of consumer bounty just about anyplace in the United States—and, increasingly, in Europe and sections of Asia as well. These shopping meccas are but one visible example of an extraordinary change in modern life. For most of history, our lives were defined by scarcity. Today, the defining feature of social, economic, and cultural life in much of the world is

abundance.

Our left brains have made us rich. Powered by armies of Drucker’s knowledge workers, the information economy has produced a standard of living in much of the developed world that would have been unfathomable to our great-grandparents.

A few examples of our abundant era:

• During much of the twentieth century, the aspiration of most middle-class Americans was to own a home and a car. Now more than two out of three Americans own the homes in which they live. (In fact, some 13 percent of homes purchased today are

second

homes).

3

As for autos, today the United States has more cars than licensed drivers—which means that, on average, everybody who can drive has a car of his own.

4

• Self-storage—a business devoted to providing people a place to house their extra stuff—has become a $17 billion annual industry in the United States, larger than the motion picture business. What’s more, the industry is growing at an even faster rate in other countries.

5

• When we can’t store our many things, we just throw them away. As business writer Polly LaBarre notes, “The United States spends more on trash bags than ninety other countries spend on

everything.

In other words, the receptacles of our

waste

cost more than all of the goods consumed by nearly half of the world’s nations.”

6

But abundance has produced an ironic result: the very triumph of L-Directed Thinking has lessened its significance. The prosperity it has unleashed has placed a premium on less rational, more R-Directed sensibilities—beauty, spirituality, emotion. For businesses, it’s no longer enough to create a product that’s reasonably priced and adequately functional. It must also be beautiful, unique, and meaningful, abiding what author Virginia Postrel calls “the aesthetic imperative.”

7

Perhaps the most telling example of this change, as our family outing to Target demonstrated, is the new middle-class obsession with design. World-famous designers such as the ones I mentioned earlier, as well as titans such as Karim Rashid and Philippe Starck, now design all manner of goods for this quintessentially middle-class, middle-brow, middle-American store. Target and other retailers have sold nearly three million units of Rashid’s Garbo molded polypropylene wastebasket. A designer wastebasket! Try explaining that one to your left brain.

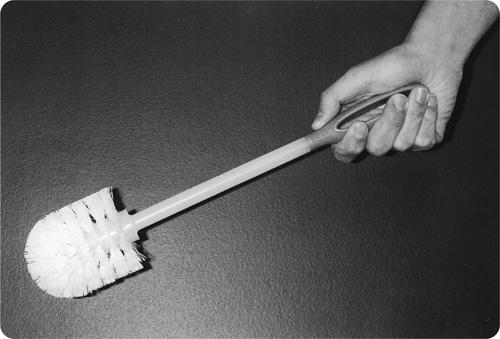

Or how about this item, which I purchased during that same Target trip?

It’s a toilet brush—a toilet brush designed by Michael Graves, a Princeton University architecture professor and one of the most renowned architects and product designers in the world. The cost: $5.99. Only against a backdrop of abundance could so many people seek beautiful trash cans and toilet brushes—converting mundane, utilitarian products into objects of desire.

In an age of abundance, appealing only to rational, logical, and functional needs is woefully insufficient. Engineers must figure out how to get things to work. But if those things are not also pleasing to the eye or compelling to the soul, few will buy them. There are too many other options. Mastery of design, empathy, play, and other seemingly “soft” aptitudes is now the main way for individuals and firms to stand out in a crowded marketplace.

Abundance elevates R-Directed Thinking another important way as well. When I’m on my deathbed, it’s unlikely that I’ll look back on my life and say, “Well, I’ve made some mistakes. But at least I snagged one of those Michael Graves toilet brushes back in 2004.” Abundance has brought beautiful things to our lives, but that bevy of material goods has not necessarily made us much happier. The paradox of prosperity is that while living standards have risen steadily decade after decade, personal, family, and life satisfaction haven’t budged. That’s why more people—liberated by prosperity but not fulfilled by it—are resolving the paradox by searching for meaning. As Columbia University’s Andrew Delbanco puts it, “The most striking feature of contemporary culture is the unslaked craving for transcendence.”

8

Visit any moderately prosperous community in the advanced world and along with the plenteous shopping opportunities, you can glimpse this quest for transcendence in action. From the mainstream embrace of once-exotic practices such as yoga and meditation to the rise of spirituality in the workplace and evangelical themes in books and movies, the pursuit of purpose and meaning has become an integral part of our lives. People everywhere have moved from focusing on the day-to-day text of their lives to the broader context. Of course, material wealth hasn’t reached everyone in the developed world, not to mention vast numbers in the less developed world. But abundance has freed literally hundreds of millions of people from the struggle for survival and, as Nobel Prize–winning economist Robert William Fogel writes, “made it possible to extend the quest for self-realization from a minute fraction of the population to almost the whole of it.”

9

On the off chance that you’re still not convinced, let me offer one last—and illuminating—statistic. Electric lighting was rare a century ago, but today it’s commonplace. Lightbulbs are cheap. Electricity is ubiquitous. Candles? Who needs them? Apparently, lots of people. In the United States, candles are a $2.4-billion-a-year business

10

—for reasons that stretch beyond the logical need for luminosity to a prosperous country’s more inchoate desire for beauty and transcendence.

Asia

Here are four people I met while researching this book:

They are the very embodiment of the knowledge worker ethic I described at the outset of this chapter. Like many bright middle-class kids, they followed their parents’ advice. They did well in high school, went on to earn either an engineering or computer science degree from a good university, and now work at a large software company, helping to write computer code for North American banks and airlines. For their high-tech work, none of these four people earns more than about $15,000 a year.

Knowledge workers, meet your new competition: Srividya, Lalit, Kavita, and Kamal of Mumbai, India.

In recent years, few issues have generated more controversy or stoked more anxiety than outsourcing. These four programmers and their counterparts throughout India, the Philippines, and China are scaring the bejeezus out of software engineers and other left-brain professionals in North America and Europe, triggering protests, boycotts, and plenty of political posturing. The computer programming they do, while not the most sophisticated that multinational companies need, is the sort of work that until recently was done almost exclusively in the United States—and that provided comfortable white-collar salaries of upward of $70,000 a year. Now twenty-five-year-old Indians are doing it—just as well, if not better; just as fast, if not faster—for the wages of a Taco Bell counter jockey. Yet, their pay, while paltry by Western standards, is roughly twenty-five times what the typical Indian earns—and affords them an upper-middle-class lifestyle with vacations and their own apartments.