A Wild Ride Through The Night (5 page)

Read A Wild Ride Through The Night Online

Authors: Walter Moers

The sea displayed scarcely a ripple as they sped across it to a peninsula not far away, which itself formed part of a largish land mass. Gustave could see from above that the peninsula was densely wooded, and that looming in the interior was a bleak mountain range. The gryphon glided down and landed on the very tip of the tongue of land. Gustave dismounted and listened apathetically to its instructions on his future movements.

‘From here on, you can only proceed by land. Flying is impossible in this air space, and I’m not designed to travel on foot. You’ll be wondering why on earth a forest reputed to be swarming with goblins and other horrific creatures could be less of a threat than the sky above it.’

Gustave did not pursue this point, so the gryphon went on, ‘I’ll tell you why: because that air space up there is full of appalling dangers! There are holes in the sky that are said to lead to other dimensions. The ethereal ocean above this territory is dominated by flying serpents and other malign creatures.’

‘I can’t see any,’ said Gustave, unimpressed.

‘But you can see the air quivering above the treetops?’

Gustave nodded. ‘It’s hot, that’s all—heated by the perpetual sunshine.’

‘Don’t you believe it! Those are aeolian slicers. They’re like glass—transparent and almost invisible, but sharp as cut-throat razors. You don’t notice them until

after

they’ve reduced you to slices.’

Gustave was growing tired of the mythical beast’s dissertation.

‘You can rest here awhile,’ it continued. ‘Your new travelling companion is on the way with your equipment. He’ll be here before long.’ The gryphon rose into the air. ‘As for your love-sickness,’ it added, ‘it’ll pass. The more your first love hurts, the quicker you’ll forget how wonderful it was. You won’t find that much of a comfort at present, but you will, believe me.’

Gustave sank to the ground, stretched out in the long grass, heaved a deep sigh, and instantly fell asleep.

GUSTAVE WAS ROUSED

by a clatter of hoofs. He opened his eyes and sleepily raised his head. All he could make out at first was a wavering figure, a creature with four legs and a human torso. Another mythical creature? A centaur?

He blinked, and his vision cleared. A magnificent silver-grey horse came trotting out of the forest with a knight on its back. The latter, who was wearing a fearsome-looking suit of black armour and a helmet with the visor closed, carried a long wooden lance in his right hand and a spiked ball-and-chain in his left.

The knight levelled his lance and cleared his throat.

‘Get ready for your last task!’ he called to Gustave, who was laboriously scrambling to his feet. The voice was deep and metallic, as though the armour itself were speaking.

‘What does he mean, my

last

task?’ thought Gustave, bewildered. ‘And why a knight?’ No one had ever said anything about doing battle with a knight. He straightened up with an effort, brushing the earth and leaves off his arms and legs. It was only then that he remembered how scantily attired he was.

Gustave decided to clear the air by appealing to reason. The knight, who was doubtless his new travelling companion, had evidently been given the wrong instructions. Someone had definitely blundered. Either that, or the figure in black was playing a silly practical joke on him.

‘Now look here,’ Gustave began, but the pugnacious warrior had spurred his horse and was galloping towards him. The ball-and-chain whistled through the air as he whirled it around his head, dust and clumps of grass went flying, and the forest floor shook in time to the charger’s hoofbeats.

Gustave tried to react as the situation warranted: he reached for his sword, but it wasn’t there any more. It was embedded in the belly of a hapless dragon lying dead on the seabed.

‘I’m a servant of Death!’ bellowed the black knight, digging his spurs into the charger’s flanks.

‘That’s no surprise,’ Gustave muttered to himself as he desperately scanned his surroundings for somewhere to take cover.

The whistle of the ball-and-chain and the thunder of hoofs combined to create a kind of music that grew louder and more menacing as the horse bounded nearer. The knight himself emitted an awe-inspiring sound which had probably served him well in many a battle—a cross between a growl and a rising scream. Its effect was not lost on Gustave, who at last decided that discretion was the better part of valour. His intention was to sprint into the nearby forest, where a horse would find it hard to follow and the knight, in his heavy armour, would also have problems. But he couldn’t move. His feet seemed to be rooted to the spot—he couldn’t budge them even an inch.

Looking down, he saw that his ankles were trapped by two tendrils—no ordinary tendrils, however. Although they were of the same olive-green colour as the other plants around, they had tiny, elfin faces, dainty but athletic bodies, and muscular-looking hands and arms. Embedded in the ground from the waist down, they wore little hats consisting of upturned flower cups.

‘Don’t run away!’ one of them called in a piping voice. ‘Stand your ground!’

‘Yes!’ snarled the other. ‘Abandon yourself to your fate!’

‘

The forest of evil spirits

,’ Gustave thought suddenly, ‘

—I must be in the midst of it already!

’

He strove to free himself, but the stubborn elves hung on tight.

‘At last there’s going to be some action around here!’ the first one crowed delightedly.

‘Yes, if you think we’re going to let you get away, you’re wrong!’ said the other. ‘We want to see the colour of your blood!’

Gustave redirected his attention to the knight, who by now was only a few lengths away. His metallic war cry had risen to a shriek, and foam was flying from the horse’s muzzle.

It seemed to Gustave that his only option was to accept the inevitable. He sank to his knees, shielding his head with his hands, and watched the galloping knight bear down on him.

He resigned himself to the following sequence of events: (a) the lance would transfix his chest with a horrid noise; (b) horse and rider would come crashing down on him, breaking every bone in his body; and (c) the black knight could then, if he chose to, knock his head off his shoulders with the ball-and-chain. This was a thoroughly realistic assessment of his immediate future—at least for as long as these obnoxious elves continued to cling to his feet, and they showed no signs of letting go.

‘You’re dead!’ yelled one.

‘Now you can surrender your soul!’ laughed the other.

What actually happened, however, was that the charging horse seemed suddenly to slow down. To be more precise,

every

movement made by the horse and its rider seemed to become more protracted, as if someone had applied the brakes to time itself.

The black knight’s voice became unnaturally deep, like the lowest note of a tuba. His mailed left fist, which was swinging the ball-and-chain, detached itself from his arm and, propelled through

the

air by the weapon’s momentum, flew off into the forest. The cast-iron ball embedded its spikes in the trunk of a birch tree, the mailed fist swung ponderously to and fro on the end of the rattling chain. Gustave stared in astonishment as the knight’s right arm fell off, leaving a hole through which he could see that the armour was empty. The left leg broke loose, keeled over sideways, and was dragged along by the stirrup, the remains of the left arm went flying, as did the other leg. The helmet, which also fell off, was as empty as everything else. Then the rest of the armour crashed to the ground. All that was left was the horse, which threw back its head and drove its hoofs into the ground. Great clods of earth went flying past Gustave’s ears as the animal skidded to a halt only inches short of him.

That was when he woke up. He was still lying where he had sunk to the ground after the gryphon had taken its leave. Standing beside him was a nag that bore not the slightest resemblance to the proud warhorse of his nightmare. Considerably leaner and far less handsome, it was pawing the ground, snorting, and nervously frisking to and fro.

‘Good morning,’ it said.

Although Gustave was surprised to encounter a horse that could speak, another beast with the power of speech was no big deal in view of recent developments, so he merely returned its salutation.

‘Good morning,’ he said sleepily.

‘My name is Pancho,’ the horse said, ‘—Pancho Sansa.’

‘Pancho Sansa?’ thought Gustave. ‘What a silly name, and why does it sound so familiar?’ Courtesy seemed to prescribe that he introduce himself likewise.

‘My name is Gustave—’

‘—Doré,’ the horse cut in. ‘Yes, I know. I’m your next travelling companion. I’m afraid I lost your new suit of armour in the forest back there. The undergrowth was so dense, it knocked the stuff off my back. I’ll show you where the pieces are lying. Then you can put on your ironmongery and we’ll go and give a few of these evil spirits what for, agreed?’

A HERD OF

graceful deer fled, startled by the intrusive sound of Pancho’s hoofs as he trotted across a verdant meadow with Gustave on his back. Gustave was in full armour once more. His accoutrements weren’t black and fearsome-looking, like those of the knight in his dream, but made of fine chased silver like the ones he had worn before.

A flock of birds with exotic plumage took wing, twittering indignantly, and disappeared into the tangle of branches and creepers. Spiders’ webs floated through the air, forming gossamer-fine rope ladders up which the little light that remained was ascending into the evening sky. Glow-worms—or were they will-o’-the-wisps?—began to dance and fill the air with multicoloured squiggles.

‘This must be the enchanted forest,’ said Gustave.

‘Know what forests give me?’ asked Pancho. ‘The creeps! Yessir, I’m more of a prairie type. Wide-open spaces, fields, meadows, deserts—even roads, provided they’re long and straight. Forests are the bitter end. Mountains are bad enough, but forests—’

‘Ssh,’ said Gustave. ‘What was that?’

Pancho gave a snort of alarm. ‘What was what?’

‘Oh, nothing,’ muttered Gustave. ‘I thought I heard something, that’s all.’

Faint singing pervaded the air of the forest, mingled with crackling, rustling noises. Now and then, acorns and twigs landed on Gustave’s helmet as if someone had deliberately chucked them at him.

‘You’re right,’ whispered Pancho, ‘this forest is bewitched.’

It seemed to Gustave that they had for some time been riding

along

the bed of a long-dried-up river. The ground was littered with big, smooth pebbles, banks of earth the height of a man towered on either side, thick with grass and bushesb, and the winding track described a series of sharp bends. The trees became steadily denser. Grotesquely stunted oaks stood cheek by jowl, intertwining their mighty branches and shutting out the evening sunlight. Before long the two travellers were overarched by an impenetrable canopy of foliage.

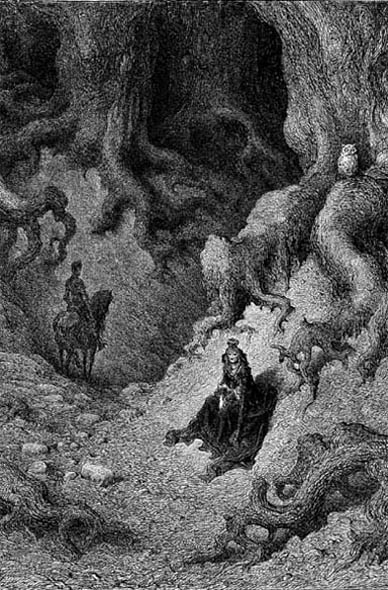

They trotted along with a sense of foreboding until, as they rounded yet another bend in the river bed, an unforeseen and startling sight met their eyes. Ahead of them, seated beneath an immense oak tree, was an old woman.

Although the roots writhing out of the ground around her looked as if they might envelop the frail old crone at any moment and drag her down into some subterranean, elfin realm, she seemed to have no fear of the enchanted forest.

She had folded her hands on her lap and was staring grimly into space. What with her sunken cheeks, the little crown on her head, and her voluminous black robe, she looked like a deposed monarch who had been banished to the depths of the forest to await death by starvation. Above her, perched on a root and imitating her grim expression, sat an owl.

Gustave and Pancho rode very, very slowly past the old lady so as not to startle her, but she took no notice of either of them, just looked straight through them as if gazing into another dismal dimension.

They were just about to round the next bend and lose sight of this strange apparition when Gustave reined in.

‘What’s the matter?’ whispered Pancho. ‘Let’s ride on. The poor old biddy’s cracked. They’re nothing but trouble, people like that.’

‘I don’t know,’ Gustave whispered back. ‘She looks

familiar

to me, somehow.’

He tugged at the bridle, wheeled Pancho round, and rode back.

‘Allow me to introduce myself,’ he said. ‘I’m Gustave Doré.’

‘Eh?’ The old woman was visibly taken aback by this courteous approach. Her vacant expression was replaced by one of dismay. She started to gesticulate, only to stop short in mid movement.

‘Doré,’ Gustave repeated politely in a somewhat louder voice. ‘Gustave Doré.’

‘Hell’s bells!’ the old woman blurted out.

‘Excuse me?’

‘Gustave Doré …’ she said, as if to herself. ‘You, of all people!’

She cackled insanely, muttered something that sounded like ‘Incredible!’ and ‘That’s all I needed!’ and brushed some invisible crumbs off her robe. Then she seemed to quieten. ‘What are

you

doing here?’ she asked curtly, looking straight at Gustave.

To his ears, the question sounded as if it had been asked by someone he’d known for a considerable time and had now re-encountered in an exotic, outlandish place. It also sounded as if that someone was anything but pleased to have renewed their acquaintance.

Closer examination convinced him that he didn’t know the old woman at all—indeed, familiar though she still seemed, he was sure he’d never seen her before. Despite the bewildering nature of the situation, he tried to answer her question as truthfully as possible.