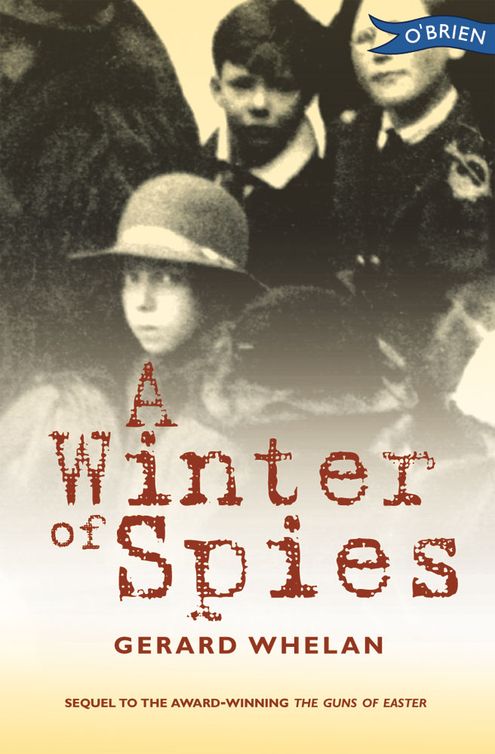

A Winter of Spies

Authors: Gerard Whelan

A Winter of Spies

‘excellent, a good story related straight as good stories deserve, enjoyable at any age’

BOOKS IRELAND

‘thrilling … adventures set against a completely realised period city, and Sarah is a terrific heroine’

RTE GUIDE

A sequel to

The Guns of Easter

In

The

Guns of Easter

(Winner of a Bisto Book of the Year Merit Award and the Eilís Dillon Memorial Award), Jimmy Conway sees first-hand the events of the Easter Rising unfolding on the streets of Dublin. He risks his life to cross the wartime city to try to get food for his starving family.

In this book, his sister Sarah becomes embroiled in an underground war, with spies and counter-spies and a confusing network of lies. Just who is lying to whom? And who, if anyone, is telling the truth?

Special Merit Award to The O’Brien Press

from

Reading Association of Ireland

‘for exceptional care, skill and professionalism in publishing, resulting in a consistently high standard in all of the children’s books published by The O’Brien Press’

Gerard Whelan

Born in Enniscorthy, County Wexford, Gerard Whelan has lived and worked in several European countries. He now lives in Dublin where he works as a fulltime father.

O

THER

B

OOKS

THE GUNS OF EASTER

W

helan’s first book has become a classic. It is winner of a Bisto Book of the Year Merit Award and the Eilís Dillon Memorial Award 1997.

DREAM INVADER

His second book was overall winner of the Bisto Book of the Year Award 1998.

INTER OF

S

PIES

Gerard Whelan

For Caitriona Walshe, Campile, Co. Wexford, whose ancestors always found something to rebel against

Thanks to TC and LM in Dublin, and DC in Laois, who put me right when I thought this story was getting a bit too nasty.

ONE OF THE WHEELS ON THE TOY BABY CARRIAGE WAS BENT

. It squeaked as Sarah Conway pushed it down the path. Eileen, the doll, lay swaddled in blankets inside. Her painted eyes looked blankly at the morning sky. Sarah hummed a lullaby under her breath. It was almost

half-past

eight.

When Sarah turned the corner onto the canal she saw a Crossley tender pulled up at the side of the street. Two Tommies and a Black and Tan were standing by Phelans' gate. She was right beside them. The sounds of a rough search came from the open doorway of the house. Wood broke against a floor or a wall. Glass smashed. Sarah stopped and leaned over the doll.

âNow, you go to sleep, Eileen,' she said. âYou need your rest.'

The men at the gate looked at her. They were bored.

âThe little one not go asleep for you, love?' one of the Tommies asked. Under his steel helmet his face was

young and open. He had big blue eyes.

âEileen is a bold girl,' Sarah told him.

âGive over, mate,' the Tan said to the soldier. âYou're wasting your time talking to these people.'

âShe's only a kid, Riggs,' the other Tommy said to the Tan. âWhat do you think she's going to do? Pull a gun out of the pram?'

The two soldiers laughed. The sounds of things

breaking

came from the house. A net curtain twitched in the window next door. A white face peeped out, then the curtain was jerked shut again.

The Tan didn't like being laughed at. He gave Sarah a nasty look.

âWhat's in that baby carriage, girlie?' he snarled at her.

âA baby,' Sarah said. The two Tommies laughed again.

âGive it a rest, Riggs,' the young one said. âShe's a kid.'

âI'm eleven now,' Sarah corrected him.

The Black and Tan, Riggs, said a dirty word.

âYou'd best get along, miss,' the other Tommy said kindly. âWe're on business here.'

âSo am I,' Sarah said.

âYou weren't,' said the Tan, âcoming here to this house, were you?'

Sarah looked at Phelans' house. They had no children, but they owned a big old lazy dog called Ranger who was always begging for food.

âI don't even know who lives here,' Sarah said. There were grenades hanging from the soldiers' webbing. The Tan had two revolvers in open holsters on his belt, like a cowboy you'd see in the picture house.

âShut up, Riggs,' said the older soldier. âNo wonder they don't like us, with pigs like you on the job.' He smiled at Sarah. âThere's bad people living here, missy,' he said. âYou wouldn't want to know them. You get off home now. Your Eileen might sleep better there.'

âAll right,' Sarah said, and went on. Before she reached the crossing two more police tenders went by. They were full of Black and Tans, bristling with rifles. Sarah turned down the back lane, still humming.

She found Simon Hughes round the bend in the lane. He wore a long black overcoat, and had his hand in one of the pockets. His face was pale and worried, his hair was uncombed. He looked shocked when he saw her.

âWell, well,' he said. âOur gal Sal.' He had a nice voice, though his accent was English. Sarah suspected that her sister Josie was sweet on him. He'd grown a lovely little moustache lately.

âSimple Simon!' she said. âIn trouble again. But you're in luck â they're lazy today. They're only starting to

surround

the place. Give me your gun.'

Simon gave her a funny look. âYou must be joking, doll,' he said.

âThere's Tans and Tommies in the street,' Sarah said calmly. âMartin sent me. Give me your gun.'

Simon Hughes thought hard. Then, reluctantly, he pulled his pistol out and handed it to her. It was a

long-barrelled

automatic, one of the ones they called âPeter the Painters'.

Sarah put the pistol in the bottom of the baby carriage and covered it with Eileen's blanket. Simon handed her two spare magazines for the gun, and she put them in her apron pocket.

âI'm going back the way I came,' she said. âYou go the other way.'

The young man stared at her.

âYes, boss,' he said sarcastically. Then he thought

better

of it. âThanks, Sal,' he said. âDoes your family know where you are?'

Sarah sniffed. âWhat do you think?' she asked.

Simon looked as though he didn't know what to think. Then he shrugged, turned and walked down the lane, trying to look casual. Sarah was sure that was easier for him without the gun. With a bit of luck he'd miss the

soldiers

altogether anyway.

âGood luck,' she said. She started back up the lane. Just as she came to the street again a group of Tans came into the laneway. Behind them walked an Auxiliary officer in his Glengarry cap and a pale man in a long overcoat with

a pistol in his hand. They all looked at her suspiciously. Riggs, the Tan who'd been at the gate, was with them. He sneered at Sarah.

âWe talked to her already,' he said to the others. âShe's just another stupid bogtrotter.'

The cheek! Sarah thought. She'd never trotted on a bog in her whole life! She'd never even seen a bog, come to that, unless you counted some of the peat beds in the mountains. But she stayed calm. The Tans went their way and she went hers. She was still humming. When she looked back the men had disappeared around the bend in the lane, all except the man with the overcoat and

pistol

. He was staring at Sarah. He looked very thoughtful.

Sarah didn't want any of these men thinking about her at all. She tried not to hurry, though she was

half-expecting

the man â he had to be some kind of detective â to call her back. Suddenly she didn't feel so adult any more. They wouldn't shoot a little girl, she told herself. Still, little girls did get shot. Just before she reached the street she looked back again, but the man was gone. Sarah felt her confidence return as she went on. For a while she listened for the shouts or shots that would say Simon had been stopped. She heard nothing, and was glad. She liked Simon.

It was still early on this Sunday morning. Eight o'clock Mass was on in Haddington Road church, and the streets

of Dublin were almost deserted. Sarah got away from the canal, and after a while turned down another lane. Two more young men were waiting for her there, Mick's friend Martin Ford and the Wexford one, Byrne. Sarah didn't really like Byrne. He was always polite, but there was something very cold about him.

The two looked tensely at Sarah until she smiled.

âHow's a girl?' Martin Ford said then.

âA girl is grand, thank you,' Sarah said. âAnd so is a

Simon

, I think.'

She took the pistol from the pram and handed it to Martin. Byrne's blank eyes searched the empty lane. He had the eyes of a killer, Ma had said one time in anger, then hushed herself, seeing Sarah there. Sarah, in spite of herself, had felt thrilled by the word. She'd have expected a killer's eyes to be wilder. Byrne's eyes were as cold as stones. You could never tell what he was thinking.

âYou're a life-saver, Sarah,' Martin Ford said. âSimon has a cool head. With no gun and an English accent he'll just walk out of there, even if he's stopped.'

Sarah gave a mock-curtsey. âThank you kindly,' she said.

Byrne looked at her and shook his head. âYou're a crazy child,' he said.

âAnd aren't you glad of it?' Sarah said tartly.

He gave her a thin smile, the only sort she'd ever seen

on his face. âGet along home with you now,' he said. âIt might get hot around here yet.'

Sarah gave him a big smile, to show him how it was done. He had no right to be so cold and serious. She knew he was only twenty, but he acted like an old man all the time. Then she turned and made towards home. The wheel on the pram squeaked all the way. Sarah felt very pleased with herself. She felt she had just taken her first steps into the adult world. It was true: she had. But it wasn't the world she expected. New worlds never are.