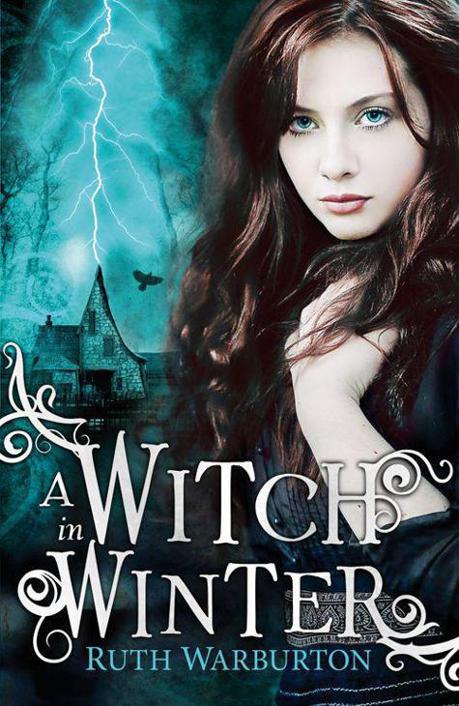

A Witch In Winter

Authors: Ruth Warburton

Copyright © 2012 Ruth Warburton

First published in Great Britain in 2012

by Hodder Children’s Books

This ebook edition published in 2012

The right of Ruth Warburton to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form, or by any means with prior permission in writing from the publishers or in the case of reprographic production in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency and may not be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

A Catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 444 90472 7

Hodder Children’s Books

A Division of Hachette Children’s Books

338 Euston Road, London NW1 3BH

An Hachette UK company

For my mum, Alison.

With love.

CHAPTER ONE

T

he first thing that hit me was the smell – damp and bitter. It was the smell of a place long shut up, of mice, bird-droppings, and rot.

‘Welcome to Wicker House,’ Dad said, and flicked a switch. Nothing happened, and he groaned.

‘Probably been disconnected. I’ll go and investigate. Here, have this.’ He pushed the torch at me. ‘I’ll get another one from the car.’

I wrapped my arms around myself, shivering as I swung the torch’s thin beam around the shadowy, cobwebbed rafters. The air in the house was even colder than the night outside.

‘Go on,’ Dad called from the car. ‘Don’t wait for me; go and explore. Why don’t you check out your bedroom – I thought you’d like the one at the top of the stairs. It’s got a lovely view.’

I didn’t want to explore. I wanted to go home – except where was home? Not London. Not any more.

Dust motes swirled, silver in the torchlight, as I pushed open a door to my right and peered into the darkness beyond. The narrow circle of the torch’s beam glittered back at me from a broken window, then traced slowly across the damp-splotched plaster. I guessed this had once been a living room, though it seemed strange to use the word ‘living’ about a place so dead and unloved.

Something moved in the dark hole of the fireplace. Images of mice, rats, huge spiders ran through my head – but when I got up the courage to shine the torch I saw only a rustle of ashes as whatever it was fled into the shadows. I thought of my best friend, Lauren, who went bleach-pale at even the idea of a mouse. She’d have been standing on a chair by now, probably screaming. The idea of Lauren’s reaction to this place made me feel better, and I reached into my pocket for my phone and started a text.

Hi Lauren, we’ve arrived in Winter. The welcome party consists of half a dozen rats and

—

I broke off. There was no signal. Well, I’d known this place would be isolated, Dad had called that ‘part of its charm’. But even so … Maybe I could get a signal upstairs.

The stairs creaked and protested every step, until I reached a landing, with a corridor stretching into darkness, lined with doors. The closest was ajar – and I put my hand on it and pushed.

For a minute I was dazzled by the moonlight flooding in. Then, as my eyes adjusted, I took in the high, vaulted ceiling, the stone window seat, and smelled the faint scent of the sea drifting through the open window.

Through the casement I could see the forest stretching out, mile after mile, and beyond a thumbnail moon cast a wavering silver path across the night-black sea. It was heart-breakingly lovely and, in that fleeting instant, I caught a glimmer of what had brought Dad to this place.

I stood, completely still, listsig still,ening to the far off sound of the waves. Then a harsh, inhuman cry ripped through the room, and a dark shape detached from the shadows. I ducked, a flurry of black wings beat the air above my head, and I caught a glimpse of an obsidian beak and a cold, black eye as the creature hunched for a second on the sill. Then it spread its wings and was gone, into the night.

My heart was thudding ridiculously, and suddenly I didn’t want to be exploring this house alone in the dark. I wanted Dad, and warmth, and light. Almost as if on cue, there was a popping sound, a blinding flash, and the light-bulb in the corridor blazed. I screwed up my eyes, dazzled by the harsh brightness after straining into the darkness.

‘Hey-hey!’ Dad’s shout echoed up the stairs. ‘Turns out the leccy wasn’t off – it was just a fuse. Come on down and I’ll give you the grand tour.’

He was waiting in the hall, his face shining with excitement. I tried to rearrange my expression into something approximating his, but it clearly didn’t work, because he put an arm around me.

‘Sorry it’s a bit of a nightmare, sweetie. The place hasn’t been occupied for years and I should have realized they’d have turned everything off. Not the best homecoming, I must admit.’

Homecoming. The word had a horribly hollow sound. Yup, this place was home now. I’d better get used to it.

‘Come on.’ Dad gave me a squeeze. ‘Let me show you around.’

As Dad took me round, I tried to find positive things to say. It was pretty hard. Everything was falling apart – even the plugs and light switches were all ancient Bakelite and looked like they’d explode if you touched them.

‘Just look at those beams,’ he exclaimed in the living room. ‘Knocks our old Georgian house into a cocked hat, eh? See those marks?’ He pointed above our heads to scratches cut deeply into the corded black wood. They looked like slashes: deep, almost savage cuts that formed a series of Vs and Ws. ‘Witch marks, according to my book. Set there to protect the house from evil spirits and stuff.’ But I didn’t have time to look properly at the scarred wood, because Dad was hurrying me on to his next exhibit.

‘And how’s that for a fireplace? You could roast an ox in there! That’s an old bread oven, I think.’ He tapped a little wooden door in the inglenook beside the fire, blackened and warped with heat. ‘I’ll have to see about getting it open one of these days. But anyway, enough of me rattling on. What do you think? Isn’t it great?’

When I didn’t respond he put his hand on my shoulder and turned me to look at him, begging me with his eyes to like it, be happy, share his enthusiasm.

‘I like all the fireplaces,’ I said evasively.

‘Well you’ll like them even more when winter comes, unless I can get the central heating in pretty pronto. But is that all you’ve got to say?’

e o

‘It’s a lot of work, Dad. How are we going to afford it?’ Even as I said it, I suddenly realized that I’d never really said those words before. I’d never had to. We hadn’t been rich, but Dad had always earned enough for what we needed.

Dad shrugged. ‘We got the place pretty cheap, considering. And I’ll do most of the work myself, which’ll cut down costs.’

‘Oh God!’ I said involuntarily in a horrified voice. Then I caught Dad’s eye and began to laugh. Dad can barely change a light-bulb, let alone conduct major house renovations. He looked offended for a minute but then began to laugh too.

‘I’ll get someone in to do the gas and electrics, at least, I promise you that.’ He put his arm around me. ‘I have a really good feeling about this place, Anna. I know it’s been a jolt for you, I do, but I honestly think we can make something of our lives here. I can do a bit of writing, grow veg – maybe I could even do B&B if money gets tight. This place just needs a little TLC to make it fantastic.’

A

little

TLC? I thought about the filth and the rats, and all the work we were going to have to do to make this place even liveable, let alone nice. And then I looked at Dad, and I thought of him back in London, sitting up night after night, his face grey with worry as he tried to make the sums add up, tried to find a way out for both of us.

‘I think,’ I said. Then I stopped.

‘Yes?’

‘I think … if anyone can do it, you can, Dad.’ I put my torch down on the mantelpiece and hugged him fiercely. Then I noticed something.

‘Hey.’ I coughed to clear my throat. ‘Look.’

I brushed away the dust that covered the fire surround, and shone my torch closer. Beneath the grime were twining vines and leaves, but that wasn’t what I’d noticed. In the centre was a carved stone shield, bearing an ornate W.

‘W for Winterson.’

‘Look at that!’ Dad said delightedly. ‘Though it’s W for Winter more likely, or maybe Wicker House. But it’s a nice omen. Now come on.’ He dropped a kiss on the top of my head. ‘Let’s go and do battle with that Aga, see if we can’t get you some tea.’

Monday was the first day of the summer term, but you wouldn’t have known it from the greyish light that trickled under the curtains. I lay in bed with the cover to my chin and listened to the wind in the trees. My body felt strange; every muscle was taut with nerves and my veins seemed full of some strange tingling liquid, as if my blood had been drained and replaced with carbonated water. It was terrifying starting a new school after ten years in the same comfortable surroundings. There had been only forty girls in the Lower Sixth of my old school – in comparison Winter High was massive. AndWinmassive scary. And co-ed.

Just to add to the stress, there was no uniform in the sixth form. Which meant I had to think about what to wear to school for the first time in my life.

Dragging myself out of bed, I opened the door to my Ikea wardrobe, which looked strange and out of place in this huge, vaulted room. At the sight of myself in the mirror inside, I groaned. I’ve never forgiven Dad for bequeathing his hair to me: wild, dark and unruly, and ready to run riot at the slightest opportunity. I suppose the rest, the pale skin and blue-grey eyes, must have come from my mother. I wouldn’t know, but that certainly wasn’t Dad’s DNA looking back at me from the mirror.

I grabbed a comb and began trying to tame my curls into something that wouldn’t get people pointing and laughing on my first day. My best hope for Winter High was not being noticed. I wasn’t planning on making any life-long friends; if I could just get through the next two years, get my A-levels, and get out, that would be good enough for me. But fitting in would be nice, and crazy-girl hair wasn’t going to help with that.