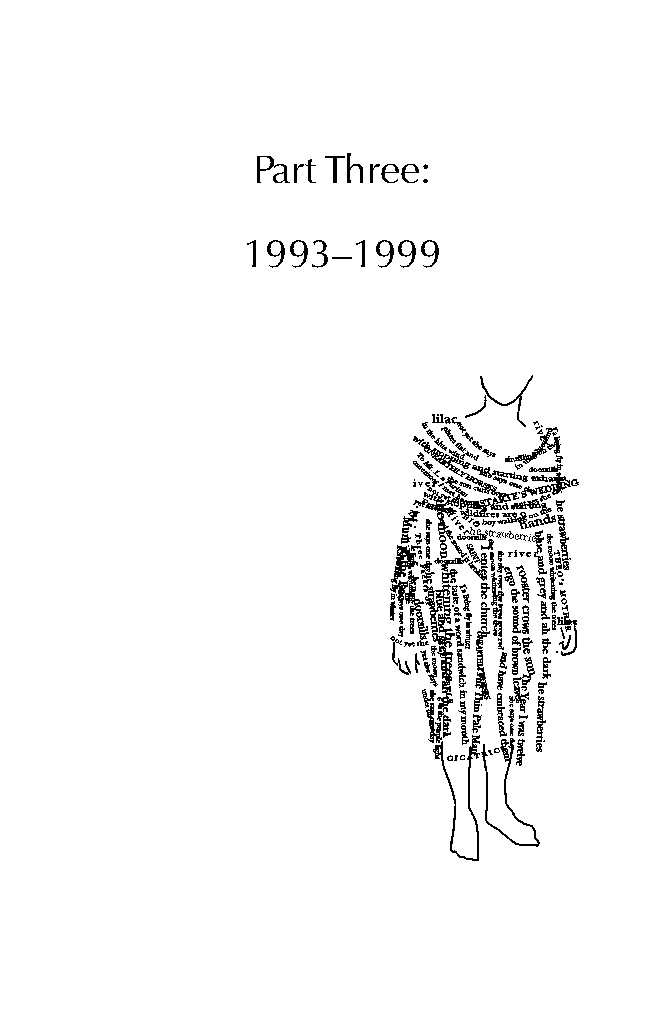

A Woman Clothed in Words (10 page)

Read A Woman Clothed in Words Online

Authors: Anne Szumigalski

Tags: #Fiction, #Non-fiction, #Abley, #Szumigalski, #Omnibus, #Governor General's Award, #Poetry, #Collection, #Drama

our feet mumbling in the dry leaves

drifts of leaves rising towards the door

drifts of leaves washing against the door

•

in the house plates are handed

for those who sit on chairs

on the uncovered floor

•

all those hands holding flat white plates

hands handling plates

white knuckles of grasping hands

plates flat and white like poems

poems rounded in colours, lilac mauve

blue and grey and ah the dark road

and oh the purple air

•

now food is bandied about

obscuring the plates

and I had thought the plates

the poems were the reason for everything

representing the possibility

of anything

don’t cover the shape

of my printed plate

I want to make out

what the whole thing’s about

•

ergo the sound of brown leaves

shuffling on the doorsills

the taste of a word sandwich in my mouth)

~~~

a boy walking on the road

to church carrying a bible

a man walking in the purple light

he disappears then appears again

still trudging the road

still with the book

under his arm

•

the early dawn in lilac

is every sacrifice unearthly horses

•

a crucifixion

naked and nailed

every cool morning a resurrection

with one foot I carelessly break ice in the ditch

•

light is lilac

I enter the church

~~~

(in the room our heads nod

as though admitting

all modesty aside

to knowledge and understanding

our teeth chew our throats swallow

•

we promise our mouths

they may talk on and on

munch on and on and on

•

outside the house

the wind gusts all of a sudden

opening the door

•

a few dud leaves

brown and curled under

wander in and sit in a meek row

on the very edge of the carpet)

~~~

after sleep rising

to the gaze of the mirror

to the knowledge of the river

•

she walked there

sometimes I met her

•

once I found her yellow scarf

•

I raised my hand

but the sun shifted

and she was gone

•

after death rising

in

the

blue wind

•

after words

•

are you the bride

am I just a lover flicker and hawk

•

sweet woman

sweet women

the sun curls over

the water and the fields

and the mountains

where everything lies like a

student priest

•

for you woman dear

t

he door to my heart opens

we have learned the odds

and have embraced them

•

the scent of lilacs in the purple air

of far Russia and her pure words

have been spoken twice over

and she said give this unknown woman

my lonely grave

•

and she said when I love I love

try to understand how it is to live

between the swords

and the stars

•

on small scraps of paper she wrote

the wonders of the inside of

the head this woman the head

of the poets of her time

and

she knows I’m a left-eyed man

you don’t get to be a saint

•

seeking an end to memory

•

here’s the river again and the ice

and Anna giving herself to love

all garments fall from her

but the garment of words

•

and what could be more beautiful

than a woman clothed in words

•

while in another century in another country

Emily Dickinson vaults the midnight horse

and gallops to her love

~~~

(the thin pale man on the road

on the opposite side of the street

what’ll I do to call him over

to my side of the world

what can I say yoohoo

you man with the scrubby beard

you erstwhile mennonite

•

he doesn’t turn his head of course

I wish he would

•

look Friesen I say look here

I have been to your house

I have eaten your good food

•

now my plate is empty

if I visit again will you

fill my bowl with salad

fill my cup with tea

•

and fill my ears with more words

than I could ever hope for

my eyes also

that I may be comforted

with the truth)

•

let’s say we can halt fear let’s say the music’s loud enough we

can hear it on our skins…

A State of Grace

Author’

s note:

The children are:

Brythyll (trout) 13–14 years old

Laurence 12 years old

Boy 7 years old

Nan 4–5 years old

Mother and father who appear generally as mere shadows in the story.

The two grandfathers who are responsible for the children’s education. One teaches them music and mathematics. The other teaches everything else.

The time is probably the thirties.

The place probably Britain (a suburb of London?).

•

Deep pools full of green fishes

– these are the words that come first to her mind upon waking, and they are not simply words, for looking down she can clearly see sinuous creatures flitting in and out of the waterweeds, and her fingers like so many pale cormorants fishing for them in the drowned sky.

No-one has ever touched the sky, but there it is, as real as numbers which surely mean nothing at all without the fingers to count them on. As real as five-finger exercises up and down the keys, marching sometimes, sometimes dancing, white and black and white and black and white again. The only colour the pink of the child’s fingers. You think so? Surely there are as many grey fingers and golden ones, and what of the black so nimble on the plastic keys connected to the hammers that connect with the strings.

The notes after all sound tinny that should be silver. And she sees again the laburnum tree in her aunt’s city garden dribbling gold onto the small space of mown grass. In her mind there is silence as deep as only the deaf can hear. Must I die, she asks before I can comprehend silence. And she lifts her fingers cold and creased from the pool, pearshaped beads falling upon the green blades of the verge.

What it is to be left to oneself so early waiting for the dawn chorus to begin. A minute and another minute and another:

twit

says the first note and then

twat,

and broader and broader until all the small insults of the tongue have become nothing but notes in a string of notes in the great first song of the birds, the many tiny pips that are part of the golden flesh of an orange.

The sun, ovoid and not yet glowing, rises dripping out of the water shooting off pale blossoms like a primrose its buds, the buds opening noisily as umbrellas. Now insects are bristling among the blades of grass, hopping and humming and beginning to bite the air with mouths as small as the points of fine needles. And she rears up only to be faced with a strange pair of eyes. Only to be held down by a pair of strange hands.

It’s much too early,

she hears herself saying. She’s annoyed that she’s laughing

when she says it. He’s closing the windows and doors, he’s taking away the garden and bringing her nothing but curtains and looming sofas and chairs uneasy in their dark corners.

Should I have brought you a rose?

His voice is like the sudden appearance of scissors brought out to snip the cords that connect her to herself. Fish swim away from fingers, or with them in their toothed mouths. Pianos float away on streams, never perhaps to be played again, gnats sink back into their beds of weedy grass, the birdsong abruptly ceases. The shutters have been closed against the closed windows.

In the darkness she thinks of a long green fish swimming inside her trying to reach that part of her mind that can understand the way he is, the way he imagines himself as a kingbird flying upwards until he breaks the sky with his crest, breaks it with a cry that is almost a song.

Another day she is looking for a home.

All this has happened in the past,

she reminds herself as she travels on through the world,

yet I need not change tense, for the present is merely a knot in the string I move through my fingers. In a moment or two it will have passed on to other hands.

And other places other lands. If she is at heart a woman, she will divide and become several interchangeable persons, then these will divide and become a crowd. You cannot call this multitude an army for each of the entities is her own person. Not one will be exactly like another. Each will think in her own chosen images, and each will dress in her own particular manner.

Here is a story that any of these persons might tell: Once an old tyrant ruled the earth and its many peoples. He it was who set words against other words and caused them to fight terrible wars over things as small as syllables. This went on for many years, but in the end people got tired of fighting and eventually settled down. This did not suit old N in the least and he soon invented another way to get them at loggerheads.

Everyone has a double somewhere in the world,

he declared. I command each of you to go forth into the world and seek your double and don’t come back home until you find that one exactly like you. No-one stirred. Everyone stayed at home and got on with daily life. Why should any of us want a double, they told him. Enough is the burden of jollity and shame that we each one of us carry forward to the grave, whenever and wherever that may be. Doubleness would multiply and not divide our sorrow.

It has been decided that the children are to choose which of the two houses the family will live in. There is no other choice, just the two. They are hesitant, even after having consulted in the back garden of Number Twenty-eight. For here is an apple tree with a short trunk springing out of the worn grass like a mushroom, its many sturdy branches all leaning to the south. Aha, the north wind, their father warns them. What do they care? A tree with enough easy branches to hold them all is a treasure, or at least an opportunity. Here they could hang like a tribe of monkeys in a cruel zoo watching their parents watching them, and behind their parents the usual row of aunts and godmothers and the two grandfathers whom fate has allotted them.