A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 (27 page)

Read A world undone: the story of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 Online

Authors: G. J. Meyer

Tags: #Military History

On Sunday, August 2, things still hung in the balance. “I suppose,” Asquith wrote that day to the young woman with whom he was conducting his own romantic intrigue, “that a good three-fourths of our own party in the House of Commons are for absolute non-interference at any price.” But as he wrote, the Germans were moving their army into Luxembourg and launching small raids into France. In the evening Berlin sent its ultimatum to Belgium, lamely stating that it had to invade Belgium before France could do so and demanding unobstructed passage for its troops. The French meanwhile were still holding their forces back from the borders, doing everything possible to make certain that Britain and the world would see the Germans as the aggressors.

Early on Monday King Albert of Belgium issued his refusal of Germany’s demands. Later in the day Germany declared war on France. Grey, the eyes of Europe on him, addressed the House of Commons. He spoke for an hour, putting all of his emphasis on the government’s efforts to keep the war from happening, on the threat that a violation of Belgium would be to Britain itself, and on his conviction that Britain must respond or surrender its honor. He kept his arguments on a high moral plane, artfully avoiding less lofty subjects such as the continental balance of power.

Not everyone was persuaded. “The Liberals, very few of them, cheered at all,” one member of the House noted. But the Conservatives “shouted with delight.” In any case a majority of the Commons was won over, and so was the public. The sole remaining questions were whether the Germans were going to pass through only a small corner of Belgium or move into its heartland, and whether the Belgians were going to resist. (The Germans, in demanding free passage through Belgium, had promised to pay for all damage done by their army.)

Tuesday brought the answers. Masses of German troops began crossing the border into Belgium and moved on Liège. King Albert made it clear that he and his countrymen intended to fight.

It was done. Before midnight Britain and Germany were at war. Some members of the cabinet resigned, but only a few, and they knew that no one cared. The pretense that only the Royal Navy would be involved was quickly forgotten. The British army prepared to fight in western Europe for the first time in exactly one hundred years.

Lloyd George, having maneuvered in such a way as to keep his position in the government without seeming to compromise the principles that had long since made him a prominent anti-imperialist, found himself cheered on August 3 as he rode through London. “This is not my crowd,” he said to his companions. “I never want to be cheered by a war crowd.”

“It is curious,” wrote Asquith, “how, going to and from the House, we are now always surrounded and escorted by cheering crowds of loafers and holiday makers. I have never before been a popular character with ‘the man in the street,’ and in all this dark and dangerous business it gives me scant pleasure. How one loathes such levity.”

Chapter 9

A Perfect Balance

“The most terrible August in the history of the world.”

—S

IR

A

RTHUR

C

ONAN

D

OYLE

T

he commander of the British Expeditionary Force, Sir John French, had arrived in France with little knowledge of where the Germans were or what they were doing or even what he was supposed to do when he found them.

French—the same Sir John French who had resigned as chief of the imperial general staff at the time of the Curragh Mutiny—carried with him written instructions from the new secretary of state for war, the formidable Field Marshal Earl Kitchener of Khartoum. These instructions were not, however, what a man in his position might have expected. They did not urge him to pursue and engage the invading Germans with all possible vigor, to remember that England expected victory, or even to support his French allies to the fullest possible extent in their hour of desperate need.

In fact, he found himself under orders to do very nearly the opposite of these things. He was to remember that his little command—a mere five divisions, four of infantry and one of cavalry—included most of Britain’s regular army and could not be spared.

“It will be obvious that the greatest care must be exercised towards a minimum of loss and wastage,” Kitchener had written. “I wish you to distinctly understand that your force is an entirely independent one and you will in no case come under the orders of any Allied general.” In other words, French was not to risk his army and was not to regard himself as subordinate to Joffre or Lanrezac or any other French general. In taking this approach, Kitchener created an abundance of problems.

Certainly the BEF, compared with the vast forces that France and Germany had already sent to the Western Front, seemed so small as to risk being trampled. Kaiser Wilhelm, drawing upon his deep reserves of foolishness in exhorting his troops to victory, had called it Britain’s “contemptibly little army.” But man for man the BEF was as good as any fighting force in the world: well trained and disciplined, accustomed to being sent out to the far corners of the world whenever the empire’s great navy was not enough. The BEF was also an appealingly human, high-spirited army. Even the rank and file were career soldiers for the most part, volunteers drawn mainly from Britain’s urban poor and working classes, more loyal to their regiments and to one another than to any sentimental notions of imperial glory, and ready to make a joke of anything. When they learned what the kaiser had said about them, they began to call themselves “the Old Contemptibles.” When the first shiploads of them crossed from Southampton to Le Havre, they found the harbor jammed with crowds who burst into the French national anthem, “La Marseillaise.” The thousands of British troops—Tommies, they were called at home—responded by bursting spontaneously not into “God Save the King” but into one of the indelicate music hall songs with which they entertained themselves while on the march. The French watched and listened reverently, some with their hands on their hearts, not understanding a word and thinking that this must be the anthem of the United Kingdom.

The BEF moved first to an assembly point just south of Belgium, and on August 20 began moving north to link up with Lanrezac’s Fifth Army and extend the French left wing. They were still en route when, on August 21, the units that Lanrezac had positioned near Charleroi on the River Sambre were struck by Bülow’s German Second Army. Sir John French, when he learned of this encounter, ordered his First Corps (two divisions commanded by Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien) to move up toward the town of Mons, about eight miles west of Charleroi. From there, it was to cover Lanrezac’s flank.

On the next day, with the Germans and French alternately attacking each other on the Sambre (Ludendorff, who happened to be in the area as a member of Bülow’s staff, organized the seizure of the bridges across the river), a scouting party of British cavalry encountered German cavalry coming out of the north. The Germans withdrew. The British, savvy veterans that they were, dismounted and began using their trenching tools to throw up earthwork defenses while Smith-Dorrien’s infantry came up from behind and joined them. They didn’t know what to expect when the sun rose, but they intended to be as ready as it was possible for men armed with little more than rifles to be.

Ahead of them in the darkness was the entire German First Army. Its commander, Kluck (it was a gift to the amateur songwriters of the BEF that his name rhymed with their favorite word), knew nothing except that his scouts had run into armed horsemen, and that they claimed those horsemen were British. It did not sound serious; Kluck’s intelligence indicated that the main British force was either not yet in France or, at worst, still a good many miles away. There seemed no need to mount an immediate attack.

Kluck at this point was an angry, frustrated man who didn’t want to be where he was and in fact shouldn’t have been there. He had recently been put under the orders of the more cautious Bülow, whose army was on his left. The Germans, like the French, were still in the early stages of learning to manage warfare on this scale, and they had not yet seen the value of creating a new level of command to direct forces as large as their right wing. Neither side had yet seen that when two or three armies are operating together and need to be coordinated, the answer is not to put the leader of one of those armies in charge of the others. It is almost inevitable, human nature being what it is, that a commander made first among equals in this way will give too much weight to the objectives and needs of his own army.

General Alexander von Kluck Commander, German First Army

An angry, frustrated man—and eager for a fight.

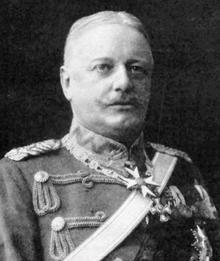

General Otto von Bülow Commander, German Second Army

Favored direct attack rather than encirclement.

This is exactly what happened between the rough-hewn Kluck and the careful, highborn Bülow. Kluck had wanted to swing wide to the right, well clear of the French. Bülow insisted that he stay close, so that their two armies—plus Max von Hausen’s Third Army on his left—would be able to deal with Lanrezac together. Kluck protested, but to no effect. Bülow was a solid professional who had long held senior positions in the German army, and a decade earlier he had been a leading candidate to succeed Schlieffen as head of the general staff, losing out to Moltke largely because he favored a direct attack on the French in case of war, rather than envelopment. His approach in August 1914 was conventional military practice; if his army locked head to head with Lanrezac’s, Kluck and Hausen would be able to protect his flanks and then try to work around Lanrezac’s flanks and surround him. But Bülow’s orthodoxy (obviously the war would have opened in an entirely different way if he rather than Moltke had been in charge of planning since 1905) cost the Germans a huge opportunity. Left free to go where he wished, Kluck would have looped around not only the French but also the forward elements of the BEF. He then could have taken Smith-Dorrien’s corps in the flank, broken it up, and pushed its disordered fragments into Lanrezac’s flank. The possible consequences were incalculable; the destruction of Lanrezac’s army—of any of the armies in the long French line—could have led to a quick end to the war in the west. Continuing to protest, appealing to Moltke but finding no support there, Kluck had no choice but to follow orders. Doing so caused him to run directly into the head of the British forces, engage them where they were strongest instead of weakest, and give them a night to consolidate their defenses because he didn’t know he was faced with anything more dangerous than a roving cavalry detachment.

On the morning of August 23 (a day marked by Japan’s declaration of war on Germany), Kluck ordered an artillery bombardment of the enemy positions in his path. When this ended at nine-thirty, thinking that the defenders must now be in disarray, his troops attacked—and were quickly shot to pieces in a field of fire so devastating that many of them thought they must be facing an army of machine guns. They attacked repeatedly and were cut down every time. What they were up against was the fruit of years of emphasis on what the British still called musketry. Every private in the BEF carried a .303 Lee Enfield rifle fitted with easily changed ten-round magazines and had been trained to hit a target fifteen times a minute at a range of three hundred yards. Most could do better than that. Every soldier was routinely given all the ammunition he wanted for practice, and high scores were rewarded with cash. These practices had been put in place after the South African War at the turn of the century, when the Tommies had found themselves outgunned by Boer farmers fighting as guerrillas, and this was the payoff.