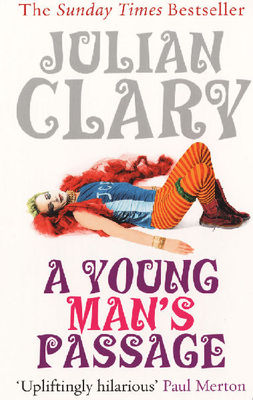

A Young Man's Passage

Read A Young Man's Passage Online

Authors: Julian Clary

Table of Contents

Contents

About the Book

A Young Man’s Passage

is Julian’s telling of his own rise and fall as Britain’s most famous, uncompromising queen. After a happy suburban upbringing, only briefly ruffled by the brutality of the monks at his school, Julian packed his bags for the bright lights of London. He soon developed a taste for shameless performance—and men. It wasn’t long before he, along with his co-star Fanny the Wonder Dog, had become The Joan Collins Fan Club and the big time was just a mince away. Fame became a mixed bag for Julian: while revelling in the rollercoaster highs, he increasingly suffered the compromises of celebrity. After the pain of losing his lover Julian’s life began to spiral out of control—and the rest, as they say, is fistory.

A Young Man’s Passage

Julian Clary

Lyrics from

Some Day I’ll Find You

(

Private Lives

): Copyright © The Estate of Noël Coward, reproduced by kind permission of Methuen Publishing Ltd.

Extract from

Human Affection

by Stevie Smith: Copyright © The Estate of James MacGibbon, reproduced by kind permission.

Extract from

Chase Me Up Farndale Avenue, S’il Vous Plaît!

by David McGillivray and Walter Zerlin Jnr: Copyright © David McGillivray and the Estate of Walter Zerlin Jnr, reproduced by kind permission.

Extract from

Paris Was Yesterday

by Janet Flanner: Copyright © Virago Press, an imprint of Time Warner Book Group UK, reproduced by kind permission.

For Nicholas Reader

With thanks to:

Peter and Brenda Clary, Tess Greenwood, Doreen Howarth, Nicholas Reader, Linda Savage, Michael Hurll, Geoff Posner, Addison Cresswell, Nina Retallick, Merryl Futerman, Paul Merton, Kirsty Lloyd-Jones, Mandy Ward, Erin Boag, Paul O’Grady, Philip Herbert, Hector Ktorides, Andrew Goodfellow, Jane Janovic, Penelope Taylor, Barb Jungr, J. Friend, Sue Holsten, David McGillivray, Richard Nelson, Chris Stagg, Michael Ferri, Rupert Hine, Jeannette Obstoj, Janet Sate, Erika Poole, Mikos, Peter Mountain, Steve McNicholas.

Some names in the book have been changed.

MALLORCA

NO ONE TOLD

me I had become an old queen. I came to the dreary realisation all by myself. I’d been hanging around the Club Barracuda, raising my eyebrows at desirable Spaniards, and was finally about to make my way home in the certain knowledge that I was of no interest and there were no athletic off-duty waiters drunk enough to emulate lust for me, when I came across my 22-year-old nephew. He was at once happy to see me and curious as to what I’m doing out at this hour at my age. It is after all 5.25 a.m. and I’m the oldest swinger in town. If only I could clear the air by having a nervous breakdown, then look back fondly at my youth, embrace middle-age spread and attempt something along the lines of living in the moment. I’m sure that’s the healthy way forward.

Forty-five. It sounds grave. It sounds like a punchline. A doctor might say it to you at the end of a sobering prognosis. ‘You see, you’re 45 . . .’ Or a psychiatrist, while demystifying your current crisis, a publicist explaining your unseemly behaviour, a personal trainer excusing the aching muscles. Eventually I say it to myself in the mirror. Forty-five. It feels important. Good bones, careful diet and discreet Botox injections do what they can but facts are facts. I’d better start wearing dark colours and stop bleaching my hair. There need to be some other changes made in the pursuit of dignity, too. I’ve scratched a living for 20-odd years as a camp comic and renowned homosexual, bespoke Nancy boy and taker-of-cock-up-arse. That will all have to go. Soon. As did the rubber and the Lycra some years ago, replaced with corsetry and glamorous suits.

I’m pleased to note that I have evolved in some ways, even if I am still a single gay man living alone in a particular square mile of north London with his small mongrel dog. (The local services I require, incidentally, are minimal: a corner shop, an off-licence, a gay pub, a first-rate sushi bar and somewhere to walk the dog.) I’m happy now, primarily.

I knew instinctively, when I arrived here almost 25 years ago, that this was my destiny. It’s as well to know. Ah, I thought then, I’ve come home. It’s a different home now, and a different mongrel too, but this is where I belong in the great scheme of things. But why?

I feel honour-bound in the writing of this book to discover what the point of myself is. The universe is not as chaotic as it may first appear to be. Nature has a reason for everything. Why am I here? Did the world at that time really need an effeminate homosexual prone to making lewd and lascivious remarks? Does everything happen for a reason or did I just get lucky?

One theory, extracted from an essay I read during my formative years, goes along the lines that Nature produces a certain number of homosexuals in each generation. Their function is to stand aside from the rest of society (busy procreating, eating food covered in breadcrumbs and living the family thing) and comment upon it. We are the outside eye, the constructive critic, diffusing with our insightful observations the inevitably tense and difficult moods that result from domestic heterosexual drudgery. This has always appealed to me. I prefer to think that gay men, lesbians and transgender folk are part of the great scheme of things. Everything has its place. I am a Catholic, after all, and it’s a comfort to me to know that God moves in mysterious ways. (He’s not the only one.)

It may be that Nature’s reasons change with time, and the current crop of freaks serves a different purpose. But I hope that I can discover the wisdom of my own creation in the course of this book. Surely, if we take a slow, selective troll through the chapters of my life, the least we can hope for is an understanding of the finished product? I’m rather hopeful. Prospective husbands need only read the paperback and proceed with caution. It will save so much time.

So here at 45 I will tarry a while, casting a bloodshot eye back at what may or may not be the first half of my natural life, but what can, come what may, unarguably be called ‘My Youth’.

THAT’S MY GENERAL

angle. I think I’ll put the emphasis on the comedy. I am a comedian, after all, so we’ll all be looking for a bit of uplifting sauce and slapstick, but expertly combined, correct me if I’m wrong, with what is loosely known as ‘light and shade’. You want the tears as well as the laughs, the lows, the traumas, the self-doubt, the drugs, the scandals. You want unexpurgated gay sex, and if you’re a

Daily Mail

reader you’ll want that followed by disease, death and loneliness. This may be just the book for you.

Once work gets a grip, depending on the work you do, it becomes the meaning of life for a while, as much an imperative as eating or sleeping. A career won’t be denied; it chomps away at your allotted 24 hours and its hunger is satisfied only temporarily before the next urge, as sure as waves roll in from the sea. And even if your work is camp comedy, it’s as all-consuming as a thesis. It has a life of its own.

In the throes of the early 1990s I might as well have been Sylvia Plath, so possessed was I. Buggery jokes, not bumble bees, perhaps, but I’d found my niche and took up the make-up brush as the poet does the pen, the teacher the chalk or the porno star the penis – i.e. with relish!

It doesn’t last, of course. Things change: self-parody creeps in, laziness rears its sleepy head. Then there are well-meaning (or otherwise) TV producers who trust their own vision more than yours. Battle with them for a few years and your resistance may cave in, the path ahead obfuscated. By then you have tax bills and mortgages, expensive tastes and expectant friends to dish out for. What was once a joy becomes a job. You’re not new and exciting, you’re old and reliable, if you’re lucky.

But why did I choose this particular line of work? It just happened, as things do. But here’s how.

So prepare for a taste of a young man’s passage.

It’s not going to be easy for any of us.

LAMONT

ONE DULL SUNDAY

afternoon in December 1993 I lay on the carpet in front of the fire and thought about my life for a while. I couldn’t indulge myself for too long as a car would be coming to collect me soon to take me to the British Comedy Awards. But the more I pondered my life, the harder it was to get up. My boyfriend had dumped me, my manager had lost interest, I was taking Valium during the day and sleeping pills at night. Even Fanny the Wonder Dog, while she hadn’t exactly withdrawn her unconditional love, had taken to avoiding me: after 13 years of sleeping in my bed (under the duvet, head on the pillow), she now retired to a spare bedroom at night.

As far as I could work out, my life had gone pear-shaped two months previously when I moved house. Could it be that mere location coupled with bricks and mortar caused my emotional well-being to evaporate so suddenly? I lay on my back and looked up at the high ceiling. I tried to focus on the empty space, on the nothingness that hovered there. It was an unnecessarily large house. Detached, as I was, with a garage and a garden. This listed Victorian home was bleak, not impressive, as I had thought when I made the purchase. It was situated on a corner and the local Holloway youths congregated there, shouting unimaginative insults whenever they saw me, even heaving a brick through the kitchen window a few weeks earlier. It had been a mistake to buy it, but I was rich and it seemed a good idea at the time. I was trying to make sense of my newly acquired fame and wealth and saw 9 Middleton Grove, London N7 as an appropriate symbol of my status.

At the third attempt I managed to get off the floor and go upstairs for a shower. It was a black-tie event so I had better make an effort and pull myself together. These award evenings could be fun if you were in the right sort of mood. Of course, I hadn’t been nominated for an award – I was presenting the award for the best comedy actress. Before I left the house I stroked a glum-looking Fanny and slipped a Valium in my pocket in case I had one of my panic attacks. I knew there was a lot of small talk ahead and I might get stuck talking to someone tiresome. In the cut-throat world of television, people sometimes enjoyed saying hurtful things. I had bumped into Chris Evans a few weeks before at the Groucho Club. ‘How are you?’ I said. ‘Your career went off the rails a couple of years ago,’ was his cheery reply.