Abigail's New Hope

A

BIGAIL’S

N

EW

H

OPE

MARY ELLIS

HARVEST HOUSE PUBLISHERS

EUGENE, OREGON

Scripture verses are taken from the

Holy Bible

, New Living Translation, copyright ©1996, 2004. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Wheaton, IL 60189 USA. All rights reserved.

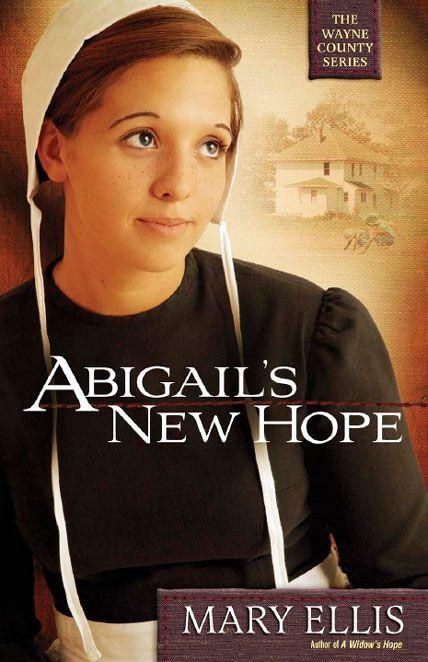

Cover by Garborg Design Works, Savage, Minnesota

Cover photos © Chris Garborg

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or to events or locales, is entirely coincidental.

ABIGAIL’S NEW HOPE

Copyright © 2011 by Mary Ellis

Published by Harvest House Publishers

Eugene, Oregon 97402

www.harvesthousepublishers.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ellis, Mary

Abigail’s new hope/ Mary Ellis.

p. cm.—(The Wayne County series ; bk. 1)

ISBN 978-0-7369-3009-3 (pbk.)

1. Midwives—Fiction. 2. Amish—Fiction. 3. Deaf—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3626.E36A63 2011

813’.6—dc22

2010039220

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, digital, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America

11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 / LB-NI / 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To the dedicated women who serve as midwives to the Amish and Mennonite communities.

May all your deliveries run smooth as silk.

Thanks to Carol Lee Shevlin, who introduced me to the New Bedford Care Center in Fresno, Ohio, a nonprofit birthing center owned and operated by local Mennonite and Amish communities.

A special thank-you to the fine officers of the Wayne County Sheriff’s Office, for answering my endless questions about department procedures and their jail facility.

Thanks also to Mrs. Sue Jarvis and the other dedicated men and women working with Jail Ministries, who bring hope, faith, and the Word of God to those incarcerated.

Thanks to Patricia Daly Marconi for her wonderful inspiration.

Thanks to my agent, Mary Sue Seymour, who had faith in me from the beginning, and to my lovely proofreader, Mrs. Joycelyn Sullivan.

Finally, thanks to my editor, Kim Moore, and the wonderful staff at Harvest House Publishers.

And thanks be to God—all things in this world are by His hand.

Contents

C

ome help us,

mamm

!” The excited voice of six-year-old Laura floated across the lawn. Abby grinned, watching her daughter and four-year-old son, Jake, chase lightning bugs through the grass with jelly jars in hand. Despite the industrious efforts of the

kinner

, the fireflies successfully evaded capture to blink and glow another night.

“Why are you two off the porch? You both were already washed for bed.” Abby walked back from the barn with her palms perched on her hips.

She glanced up as a squeak from the screen door signaled the arrival of the final Graber family member, her

ehemann

of ten years. “I thought you were reading them a story,” she said with a sly smile.

Daniel slicked a hand through his thick hair, his hat nowhere in sight. Then he braced calloused palms against the porch rail. “Relax, wife. That grass looks pretty clean from where I’m standing. You won’t have to start from scratch. Didn’t it rain just the other day?” His smile deepened the lines around his eyes. With the setting sun glinting off his sun-burnished nose, he looked as mischievous as one of their children.

Abby watched the warm summer night unfold around her family with no desire to scold. The young ones would have the rest of their lives to have perfectly clean feet, but the summers of childhood were numbered. Besides, it was too nice an evening for anyone to go to bed on time. Walking up the porch steps, she stepped easily into Daniel’s strong arms and rested her head against his shoulder. Within his embrace, and with her two healthy offspring darting about like honeybees in spring clover, she savored the almost-longest day of the year.

Swifts and swallows made their final canvass above the meadow before settling for the night in barn rafter nests or in the hollows of dead trees. Upon their exit from the sky, bats would take their place, swooping and soaring on wind currents, gobbling pesky mosquitoes. The breeze, scented with the last of the lilacs and the first of the honeysuckle, felt cool on her overheated skin.

“Everything all charged up for the night?” he asked close to her ear.

Daniel’s question, the same one he asked nearly every night since she’d become a midwife, broke the idyllic trance she had wandered into—the all’s-well-with-the-world feeling one gets after a satisfying day. “

Jah

,” she murmured. “I ran the generator long enough to charge my battery packs. And I put a fresh battery in my cell phone for tonight, but I don’t expect any middle-of-the-night calls. After yesterday’s delivery, no babies are expected for several weeks.”

“Hmm,” he concluded, nuzzling the top of her head. “We both know how well babies stick to doctors’ timetables. I’m fixing a cup of tea and heading upstairs. Yours will be cooling on the table for whenever you’re ready.” He brushed his lips across the top of her

kapp

before going inside, the screen door slamming behind him.

The nice thing about being married for ten years is that a person gets to know someone very well. Daniel Graber knew she enjoyed her beverages at room temperature—not too hot and not too cold. And she knew he needed to take mental inventory before going to bed to make sure the family’s ducks were all in a row. So she didn’t mind being asked about her cell phone charger each evening.

After all, a midwife, even an Amish midwife, needed to be accessible twenty-four hours a day. The

Ordnung

, or rules that governed their Old Order district, didn’t stipulate how Amish wives had their babies. A woman could have an obstetrician deliver at an English hospital, or she could go to a birthing center where a specially trained, certified nurse-midwife would bring her baby into the world. But many Old Order Amish preferred to have their babies at home, the center of their rural lives. Unlike their English counterparts, they usually continued to work during labor—washing dishes, picking beans in the garden, even giving the porch rocker a fresh coat of paint—until the baby made its grand entrance.