Aboard Cabrillo's Galleon (14 page)

Read Aboard Cabrillo's Galleon Online

Authors: Christine Echeverria Bender

Again the rigid bow was made, but soon cups of the requested liquid were set before the captain-general and his guests.

After his first sip, Captain Ferrelo said, “I have heard, sir, that you drink chocolate every day.”

“I have done so whenever possible since first tasting it,” said Cabrillo. “The beans used in our drinks were grown on my own encomienda. With the Mayans cultivating it for centuries, I am happy that Spaniards can also reap its rewards. Mayan holy men once used it in their religious ceremonies and some probably still do. The Aztecs believe it comes from one of their gods, and that it will bestow good health. Perhaps there is some truth to the claim. I suspect that drinking chocolate has helped me keep so many of my teeth.”

“Do they not also believe, sir,” said Correa with a speculative expression, “that chocolate enhances a man's prowess and potency? Perhaps that is also true.”

Cabrillo raised his cup in toast to such a possibility.

As Captain Ferrelo sipped his spicy, bitter drink, he noticed that Father Gamboa was merely making a show of drinking his. He said to the priest, “A thought just came to me, Father, about a rumor I heard recently. I was told that a nun has concocted a formula for chocolate that has removed the bitterness.”

Father Gamboa shifted uneasily, but every other diner found this news to be of great interest and they cast their expectant eyes upon him. “Captain Ferrelo,” said the priest, “if I knew of such a formula, I hope you would not ask me to divulge such a secret.”

In various glances the officers all acclaimed that they would indeed ask such a thing.

“It is not even

our

secret,” Father Gamboa tried again. “It belongs to the Dominican order rather than the friars of St. Augustine.”

“Well then,” proclaimed Correa, “If the Dominicans have already shared it with the Augustinians, just how secret can it be? Besides, our faith surely does not hold chocolate to be sanctified. To put such heavenly value on a victual would be a sacrilege, would it not?”

Father Gamboa decided that his best chance at maintaining discretion lay in attempting a compromise. “Dear gentlemen, I offer to do this much and hope you will be satisfied. I will look into the captain-general's supplies, and if all of the needed ingredients are among them, I will make you the chocolate myself.”

“Fine! Fine!”

“Very well, tomorrow evening then?”

“Tomorrow? Why wait, Father?” demanded Correa, standing and stepping behind the priest to pull his chair out for him.

Resignedly, Father Gamboa signaled Paulo to accompany him to the captain-general's stores chest. Within moments Paulo was sent back to the diners while Father Gamboa headed with a pot and an armful of ingredients to the ship's fogon, where he could work his magic in solitude over the glowing embers of the firebox.

The officers continued to chat easily among themselves but now and then the attention of each broke off to listen to the activities of Father Gamboa. Although it seemed longer, in only a few minutes the priest called to Paulo, and both of them reappeared with vessels full of the awaited brew.

As each man savored the thick, sweet richness his eyes brightened with surprise and delight. A round of “Bravo, Father! Well done!” circled the cabin, and Father Gamboa bowed humbly.

“Not a trace of chili peppers, and the bitterness

is

gone!” said Ferrelo.

“Why, this is creamy,” said Cabrillo. “Our good cow must have contributed to our cups.”

“I taste sugar and vanilla,” said Correa, licking his upper lip.

“And cinnamon,” said San Remón.

“And even nutmeg,” said Cabrillo, taking another drink. “Though I ration such spices dearly this

is

divine, worth every grain of seasoning used.”

Cabrillo said to his servant, “Come, Paulo, you must taste this, so you can do your best to recreate it without our extracting the secret from Father Gamboa.”

Paulo took Cabrillo's cup and brought it to his lips. With an expression of intense concentration he let the liquid circle his tongue before swallowing. His grumpy, aloof expression gave way to a smile. “I may need another swallow or two, sir, so I will remember.”

All of them laughed. “Let it not be said that I withheld my chocolate from a man of science. Let the rest be consigned to your memory.”

Disappointment flickered across Manuel and Mateo's faces, who had been hoping for a small sip from the captain-general's cup. But they both brightened when Cabrillo said, “Paulo, why not set to it at once while the original brew is still fresh? Make a thorough study of it, and let Mateo and Manuel help with the tasting of your reproductions.” Seldom had so welcome an assignment been issued, and the three were soon out the cabin door.

After the rest of the cups had been emptied to the appreciative smacking of lips, the dinner guests prepared to take their leave. Father Gamboa, however, hung back and asked, “Captain-General, may I have a moment?”

Cabrillo agreed and the two men sat down again, the oil lamps bestowing a soft glow to their sun and wind-burned features. Father Gamboa asked, “May I speak freely, sir?”

“Always, Father.”

“It appears to me, sir, that something has caused you to form a poor opinion of Father Lezcano. He was not invited to dine with us this evening, and I have seen disapproval, no, perhaps a better word is distrust, when you speak to or even look upon him. Yet you allow him to groom your most prized horse that very few others are permitted to approach. I am confused and unsettled by it all, as are others. This trouble between you, sir, is it something I can help to repair?”

Cabrillo folded his hands together and laid them on the table. “Did Father Lezcano give you no explanation of what has occurred?”

“None, sir. He has refused to discuss it, and he generally confides in me. I have even suggested that his silence could be sinful if any harm comes from it, and still he says nothing.”

Cabrillo had lifted an olive from its bowl but it still rested in his fingers. He said softly, “Truly? The man has the ability to repeatedly surprise me.”

“Is it possible, sir, that you are mistaken about him? He shows the deepest dedication to his faith and to his role on this voyage... and to you.”

Even more thoughtfully, Cabrillo admitted, “I let him share in Viento's care on the chance that he indeed means well. But you are quite right about my lingering mistrust of him.”

“I am willing to stake your benevolence toward me, Captain-General, a thing I value greatly, and to pledge my word on the belief that Father Lezcano is honorable.”

Without haste Cabrillo said, “The fact that he has held his tongue about our past encounters tells me much. Very well, Father, if you see such unquestionable good in him, I will surrender my prejudices as far as I am able.”

Relieved and pleased, Father said, “God blesses a generous man, sir.”

“Do not offer me grace that is undeserved, Father. I merely try to interpret and lead fairly, and in this I may have judged wrongly. If that is all, Father, will you please find Father Lezcano and send him to me?”

Father Gamboa bowed and departed, returned shortly with his brother priest a step behind, ushered him into Cabrillo's cabin, and immediately left them alone.

What exactly was exchanged between the young priest and the captain-general that evening was never revealed to Father Gamboa or anyone else, but from that time forward there was an improvement in the consideration Cabrillo showed toward Lezcano. Perceptive to his master's unspoken permission, Manuel began to more openly display his own growing esteem for the priest. The rest of the crew noticed the change as well, and as with the resolution of any tensions between superiors, it put the men more at ease.

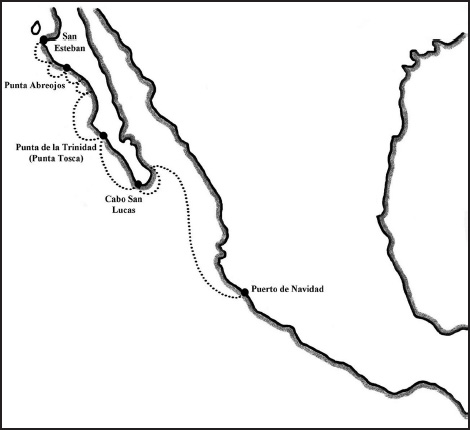

When the fleet left San Lucas on July 8, sailed to Trinidad Point, and was held there for three days by a tight-fisted wind, the two were seen together often. If an occasion arose for Father Gamboa to be invited to the commander's cabin, Father Lezcano's presence was also requested. Once, Cabrillo publicly praised Father Lezcano for his devoted care of Viento. Much to Father Gamboa's gratification, and a little to his surprise, there even seemed to be threads of camaraderie being woven between them.

As they sailed ever farther up the coast, Captain Correa frequently came aboard the

San Salvador

at the captain-general's bidding. Correa had seen this treeless, mountainless shoreline while a part of the Bolaños expedition, and Cabrillo questioned him minutely as they studied the land and their charts and speculated about when they might sight their first Indians.

Heading into Puerta de Madalena, whales numbering in the dozens spouted, rolled, and breached in undaunted proximity to the ships. As far up the beach as the eye could trace skeletons of the great beasts, washed ashore over the ages, now littered the sand. Gulls circled and scolded overhead as the ships drifted gently to this new anchorage. Other birds, feathered beasts of every color, size, and form, flitted and cried amongst the bushes or dove to scoop a prize from the innumerable schools of sardines.

Scanning the scene from the railing, assessing the potential bounty this fauna would provide to any human inhabitants, Cabrillo concluded, “If there are no Indians here, there most certainly should be.”

He chose to be among the initial scouting party, and once on the sand he and his men paused beside a monstrous cetacean spine that had long since been washed clean and pitted by the elements. “As I suspected,” he said to Vargas as he looked the skeleton over, “several of the smaller ribs have been removed. Likely used to construct shelters.”

“They've been taken from the next one, too, sir,” Vargas said, pointing to a carcass thirty feet up the beach.

“Keep a sharp eye,” Cabrillo said to his soldiers, who were already tautly alert. He gave the area a sweeping glance but other than the birds nothing stirred. With Manuel standing guardedly by, Cabrillo allowed his fascination to be recaptured by the whalebones. He ran a hand over the porous surface of the long skull, and then stepped inside the frame, straddling a gap between two vertebrae and spreading his arms wide between a pair of ribs still attached to the spine. He could just touch their inside edges. Letting his arms fall, he said in wonderment, “This mighty fish could have fed a village for months.”

“A big village, sir,” said Father Lezcano.

Drawing his men and himself away from the baleen cemetery at last, Cabrillo easily found a path that had been used not long ago by the natives. They searched, expectant and even hopeful, but many minutes and then two hours passed without an Indian sighting. If any were near, they remained artfully hidden. The men of the fleet lingered long enough for Cabrillo to make note of what they'd seen before heading back to the boats.

Setting sails against headwinds, the fleet was forced to channel its way through pod after pod of whales swimming in previously unimagined numbers to reach Puerto de Santiago. After nudging a lane between the massive bodies to reach an anchorage near nightfall, the whales began to bump the ships with such regularity that concern began to build as to whether they might cause significant damage. Faced with the risk of leaving an unfamiliar port during an hour of darkness or dealing with the whales where they lay, Cabrillo called for his pilot and shipmaster and said, “Well, gentlemen, before we become any more like grist under these unrelenting millstones, I must give the unique order to make as much clamor as necessary to keep these cursed whales from the sides of our vessels. Please pass the word along, Master Uribe.”

To help, Father Gamboa immediately brought out his bagpipes, but his well-intended music seemed to have the unanticipated effect of drawing the whales closer rather than repel them, and he almost immediately ceased his piping. At a signal from Master Uribe drums of every shape, size, and materialâincluding the temporarily adopted bombardeta, swivel guns, and kegsâwere beaten upon amid a chorus of earsplitting yells from the drummers, and the resulting din was loud enough to frighten any whale, bird, or unsuspecting human for miles around. These noise-making activities began with merry, rowdy enthusiasm as a welcome reprieve from the routine of shipboard life, but within an hour the men's arms grew weary and their heads developed a pounding ache that pulsed painfully to the cadence of their drumming.

Cabrillo, too, soon yearned for silence, but every time he ordered the drummers to still their instruments the whales began to draw near and shove the ships anew, so men were ordered to resume beating with their billets, knife hilts, kindling sticks, or whatever else was at hand. It was an exhausting, restless night that made even the most even-tempered of the men growl with longing for their habitual practices. With barely enough light to make their way clear of the bay and with all ears ringing after so prolonged a period of clamor, Cabrillo made sail and aimed his fleet's sterns at Puerto de Santiago.