Aboard Cabrillo's Galleon (38 page)

Read Aboard Cabrillo's Galleon Online

Authors: Christine Echeverria Bender

The priest readily agreed, the crew soon collected on the main deck, and the

San Miguel

hauled in close to leeward. Though these sailors and soldiers had been wrestling the storm to the point of collapse, these ragged men who had become brothers over the long months at sea, they now found strength enough to cry out “amen” with real enthusiasm as Father Lezcano pleaded to their Savior and his holy mother for the safety of their lost fellows. With the heads of the

San Salvador's

men bowed they did not see the lowered heads of Father Gamboa, the officers, and crewmembers of the

San Miguel

but now and again their words would reach them. As Father Lezcano's final prayer ended the men shifted, walked, or limped away, all wearing expressions of grim resolution. They must leave the fate of

La Victoria

and themselves in hands far more powerful than their own.

Cabrillo returned to steerage to adjust their course and then again found his well-worn planks on the stern deck. Midnight came and went, and though he ostensibly relinquished his watch at the appointed hour, he remained in the open air. Tonight, even Father Lezcano could not convince him to go inside and sleep.

The next morning's steely sky dawned hushed but brooding, and the captain-general at last went to his cabin but only to record their progress throughout the night. Master Uribe found him there, pouring over some notes on his writing desk, and he announced excitedly, “Captain-General, land lies to the northeast.”

Cabrillo was surprised he hadn't heard a shout from the lookout, but he was on his feet and reaching for his jacket as he asked, “Any sign of her?”

“None, sir, but we may spot her when we round the arc of the point ahead. There appears to be a cove beyond.”

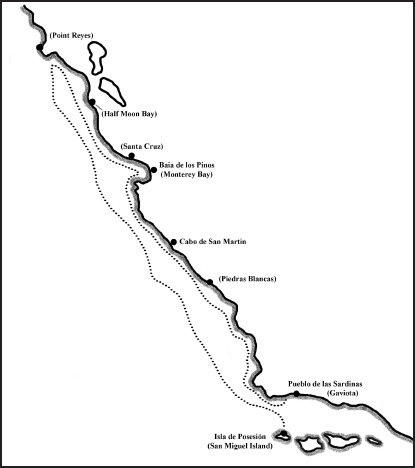

They sailed on toward noon only to discover that the approaching coast rose steeply into a craggy mountain range, and the ocean still swelled much too violently to permit an anchorage near enough to shore for a landing. Before the sun's zenith could pass, Cabrillo and San Remón gauged its altitude and agreed on a measurement of 40° north. Not long afterward Master Uribe's earlier prediction came true, if a little farther up the coast than anticipated, in the form of a cape. As it opened before them all eyes sharpened their hunt for

La Victoria

, but to no avail. With heavy disappointment they anchored to rest muscle and will and to better bind the seeping wounds of their ships.

Cabrillo could not fully appreciate the beauty of the high cliffs robed in a forest of pines. Instead, every color and dimension seemed sharpened by uneasiness for his ship; every breath of the pine-scented air seemed to carry the bite of potential tragedy. Even so, he was not completely immune to this natural feast for the senses, and he recalled his previous burning desire to see the living trees that had provided the colossal driftwood they'd stumbled across on the island so far to the south. But that aspiration could not be fulfilled now, not with such imperative matters superceding it. Mustering the hope to one day return and wander these mountains and agreeing with Master Uribe's suggestion, he named the harbor Cabo de Pinos.

Each turning of the afternoon glass, each calling out of the half-hour, accentuated the heaviness of heart for the men yearning to spot a familiar sail on the horizon. Work went on and glances offshore became fewer. Eventually the hopes of even the most optimistic and those most determined to buoy the others began to falter. Light was fading when Cabrillo sent invitations to the officers of both ships to dine with him.

After a crowded supper marked by unfocused appetites and stilted conversations, Cabrillo sat amid the officers of the

San Miguel

, Pilot San Remón, Master Uribe, and Father Lezcano, while Paulo, Manuel, and Mateo attended to them. Captain Correa and the other visitors all suspected the basis for this meeting and despite several efforts to speak of other things the talk finally dwindled to an expectant hush. Correa cleared his throat and fixed his gaze on the lamp.

At last the captain-general stilled the fork he'd been teetering between his fingers, slowly set it down, and said gravely, “Gentlemen, our present situation must be faced and dealt with.” Folding his hands together on the tabletop, he went on, saying, “There would be great risk in asking our ships to withstand the heavy storms of open sea without comprehensive repairs, which require an adequate harbor and significant time. Here, the weather is getting much colder and food sources are likely scarce and hard to obtain. Although wood surrounds us in abundance, gathering as much as would be necessary from those heights would expend much energy, and collecting enough water may also pose difficulties. For these reasons this harbor will not meet our needs for full repairs. We are left with the choice of turning back or pushing ahead. But even if every man of us was willing to accept the hazards of making hasty repairs and sailing on toward China, foremost among our reasons for yielding this position we have fought to reach is that there may be survivors behind us, men that we can aid. I will not abandon them without a thorough search.”

Although everyone in the room had known these harsh truths and not one of them disagreed with their commander's intentions, hearing the words fall with such finality from his lips, understanding what surrendering this attempt meant to him, to all of them, was enough to cause sharp pain. Cabrillo gave them a minute: time to voice an objection. None came.

Their solidarity touched his battered spirit deeply, and his tone weakened as he said, “Our new course, to the south, is decided, then. Tomorrow, we will turn back.” He briefly met their individual gazes. “For all that each of you has given to our mission thus far and to me, I am profoundly grateful.”

At this last word his voice faltered and his gaze fell.

No one could speak, and as silence reigned over the group Mateo turned his face to the wall to hide his tears. It was Father Lezcano who dispelled the quiet by saying, “The captain-general has asked me to remain and pray with him, gentlemen. Will you kindly excuse us?” With a deliberation and deference that expressed what was left unsaid, the officers stood and bowed to their commander as they filed out, and as Pilot San Remón left the chamber he gently closed the door behind him.

Manuel went to Mateo and drew him to a far corner of the cabin. Paulo slowly rolled the cloth from the table and then stood with his back against the door, holding the bundle as if it were a swaddled baby, his head down and his eyes closed. Pulling one of the four holy books he possessed from his robe, Father Lezcano glanced at Cabrillo's drawn face and lowered eyelids, and began to read.

Chapter 20

H

OPES SURRENDERED

,

HOPES FULFILLED

W

earing a weary expression that seemed almost calm, Cabrillo stood before the gathering men with his back turned to a golden sunrise. During the lengthy hours of the night he'd beaten back the personal demons that had still hovered after Father Lezcano's departure. Now the time had come to voice his decision to the crews, though word had undoubtedly spread to many of them already. The

San Miguel

floated close by, holding her position and awaiting the coming words from the fleet's commander.

“Men,” he called out in a loud, clear voice, “during the storm you fought with the courage of lions, believing as you struggled that we would sail on to reach our goal in the East. But by every sign nature has given us, that end still lies far from our grasp, farther than we can hope to reach before the worst of winter arrives. For now, we must head for a warmer harbor and make repairs. This will postpone any reward for our labors but we

will

sail north again when the weather allows. Also, and certainly most important to us all, by retracing a portion of our previous route, we will seize the best chance of finding

La Victoria

.”

Little more than a sigh was heard in reaction to his announcement. Though the expressions of a number of men showed relief, most faces reflected the same disappointment their leaders were trying to conceal. Only a few, a handful of rowers aboard the

San Miguel

, bent their heads together and muttered in disgust.

Cabrillo went on, his voice gaining power with each phrase. “As we sail southward each man and boy must keep a sharp watch. We must find that ship. Hear me, men! If she carries but a single survivor, we must find her!”

Shouts and raised fists demonstrated their willingness to accept Cabrillo's challenge, no matter how unlikely the prospects for success. One seaman stepped forward and avowed, “If she's still afloat, sir, we'll spy her out!”

Another cried, “Nary a floating stick will get by us, sir!”

Cabrillo watched them, silently praying their faith wouldn't be crushed.

As the crews retook their stations the captain-general called out the new course to his helmsman, and the two ships turned their bowsprits away from the land of their ambitions. Everyone on the decks glued his gaze to what lay before and around them in search of a sail, barrel, mast, or body.

Through the early hours they sailed swiftly on, covering many leagues along the coast. As the day aged, men who had strained their vision in the hope of being the first to notice anything unnatural now let their gazes stray. And they began to wonder, “Shouldn't we have seen something by now, some token of

La Victoria's

survival or destruction?” Many in the crew began to believe what they had refused to accept earlier; that the storm had overwhelmed

La Victoria

as it had countless other ships, and the sea had claimed those aboard for its own. When mile after additional mile revealed nothing they occasionally turned toward Cabrillo, attempting to guess his thoughts and anticipate his mood. Father Lezcano and Manuel kept a determined watch and prayed for an unlikely sighting, not only for the sakes of their sailing companions but also for the well-being of their captain-general.

Cabrillo would not leave the decks, not even to eat, and his probing glances swept the sea and shore with an intensity that only seemed to grow as the hours of remaining daylight diminished. Watching him, a few of his men wondered if he hoped to raise his lost ship from the depths by the sheer force of his will. The sun had been lowering for several hours, and its beams were breaking through a canopy of uneven clouds when Mateo approached Cabrillo with tentative steps. The captain-general did not stir, but Mateo said, “Sir?”

Cabrillo did not take his gaze from the sea.

“Sir,” Mateo tried again, “Paulo asks that you come to your table. You have eaten nothing but a little cheese today, sir.”

When no answer came Mateo was about to speak for the third time when Cabrillo said, “Tell Paulo I am not hungry, Mateo.”

Sucking in a strengthening breath, Mateo said, “Sir, uncle, please.”

“Uncle, is it?” At last Cabrillo looked at him and saw the worry and affection reflected there.

Momentarily stripped of a layer of emotional armor, Cabrillo allowed himself to feel his own exhaustion, his hunger, and even a small portion of his anguish. These sensations were not enough, however, to slacken his scrutiny while there was still sunlight. “Soon, Mateo,” he gave the boy. “Tell Paulo I will come soon, and then I will eat my fill.”

Mateo recognized this as a dismissal, but he could not bring himself to leave him yet. Cabrillo reached out and laid his hand on the boy's weather-tangled hair in a gesture that looked like a benediction. Father Lezcano, who had approached them quietly, stepped closer and said, “Come, Mateo.”

As the boy reluctantly began to turn away his head lifted and his body went suddenly rigid. His eyes bulged, and he began to gasp, “Uh, uh, uh!” in such strident tones that many turned toward him. Cabrillo grabbed his shoulders, but Mateo jerked away and aimed a flailing arm toward the coast. Before the boy could utter an intelligible word the lookout screamed, “Captain-General, a sail ahead! A point off the port bow! A sail! A sail!”

Cabrillo's gaze flew in that direction, where it found and clung to white patches of canvas hugging the coast at least six miles ahead. Wild cheers burst from his men, and Cabrillo's haggard face shone with the overpowering sense of gratitude and relief that swept through him. She was safe.

La Victoria

was safe. After the initial moments of elation, however, Andrés de Urdaneta's cautioning words suddenly stung the captain-general's memory, and his expression abruptly wavered. Before their departure from Navidad his friend had said, “If you spot a Portuguese ship, beware.” He had been advising Cabrillo to keep poison close at hand in the event he was captured during the voyage, a suggestion that had never been seriously considered. Now, with the ship ahead still too far away to clearly distinguish, he realized that she could be Portuguese, or even English. If so, given their weakened condition, what trials might await them?