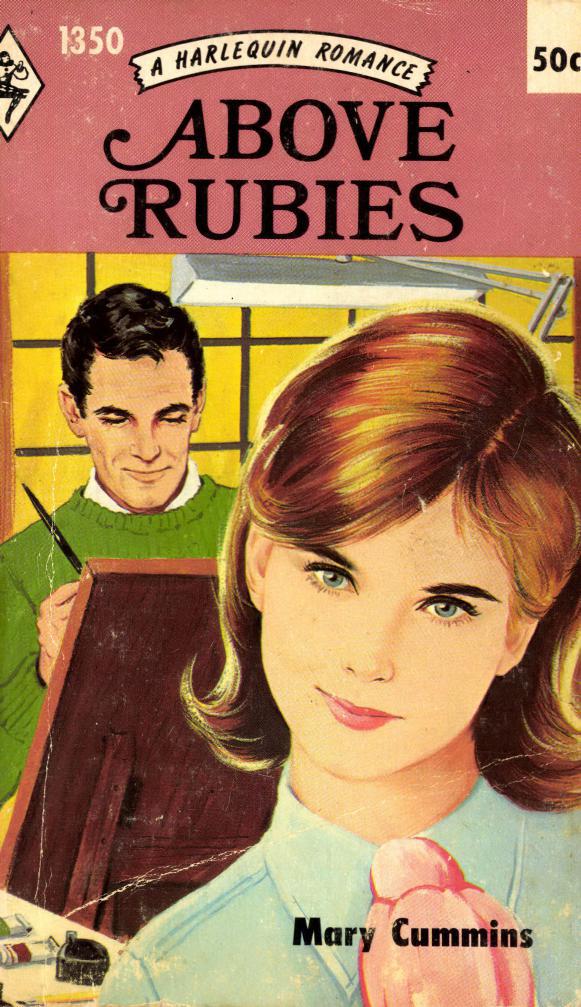

Above Rubies

Authors: Mary Cummins

ABOVE RUBIES

Mary Cummins

Merry was determined to get away from her selfish aunt and uncle, and live in the quiet Scottish village where she had been left a house—but her calculating cousin Sylvia seemed equally determined to spoil all Merry’s plans.

CHAPTER

1

MERRY came downstairs, quietly, a small suitcase in her hand, the rest of her luggage piled in the hall. The taxi was due in another fifteen minutes, just enough time to say goodbye to Aunt Elizabeth and Uncle George.

They were both sitting in the lounge, and as she walked in Merry could feel the strength of their disapproval in the atmosphere. It was a large room, ostentatious rather than tasteful. Everything had been chosen with a view to the maximum of ease and comfort, but on Merry it had had the opposite effect, and in the three years she had lived in Carlisle, she had come to feel that it was ready to smother her. Now she could hardly believe that in a few more minutes she would be leaving it all behind, and it was difficult to keep the elation out of her voice.

“I’m ready now, Aunt Elizabeth. Everything’s packed, and I’ve left the room tidy. I do hope you’ll both come and visit me after I’ve

settled down at Kilbraggan.”

Elizabeth Neilson ignored her for a full minute, carefully leafing over her glossy magazine pages with long slender white fingers, then looked up at her niece.

“We can only hope you won’t regret your decision, Merry,” she said coolly. “Beau Ness hardly seems a suitable house for a young girl of nineteen to live in by herself. I don’t know what Ellen was thinking of to leave it all to you. After all, she was as much my friend as your mother’s, and Sylvia has as much claim as you have...”

“She thought I would love it, Aunt Elizabeth, and I do.”

“... and it seems to be singularly puzzling that she should only think of you,” went on her aunt, as though Merry hadn’t spoken, while Uncle George cleared his throat and rustled his paper. “You must have influenced her in some way, Merry, when you went to stay with her on holidays, instead of travelling on the Continent like dear Sylvia. A girl should broaden her horizons and not insinuate herself with a maiden lady.”

“Oh, but I didn’t

...”

“Though who would have thought that Ellen Blayne had a bad heart? She was only in her fifties, after all. It should be a warning to you, Merry, not to live in that house alone. You should have taken your Uncle George’s advice, and let him sell it for you, and invest the money. Shouldn’t she, George?”

“Very unwise of you, my dear,” her uncle rumbled, clearing his throat again. “Might be difficult to sell in a few months’ time. Mortgages are hard these days, and it’s getting to the wrong time of year for Kilbraggan. These Scotch villages..

.”

“Scottish,” mumbled Merry.

“...

are all very well in the height of the season, but they’re hopeless in winter. No good at all. It might take overspill from Hillington, but it isn’t a very smart area.”

Merry glanced at the clock, wishing the taxi would come soon. She’d been over all this before with both Aunt Elizabeth and Uncle George, while her cousin, Sylvia, sulked disdainfully. Her Aunt Ellen had predicted trouble for her when she asked her to promise to look after Beau Ness.

“They’d just sell my lovely house, darling,” she had said, looking round the beautiful long sitting-room with the old polished furniture and brasses which winked in the firelight. “They’d never love Beau Ness as we do. They couldn’t even love

you,

though your father was Elizabeth’s only brother. I wanted to take you when he died in that plane crash on his way home from Nigeria. That was when you were at that awful boarding school.”

“It wasn’t so bad,” said Merry, smiling with affection at the one woman who had really loved her since her mother died. “As you should know!”

“It was in your mother’s day, and mine.”

“Times have changed, though, Aunt Ellen, and Daddy had to leave me somewhere. He didn’t earn much as a missionary.”

“Well, you won’t earn much as a writer,” said Ellen, “but if it’s what you want to do, then stick to it like glue. Don’t let Elizabeth push you into anything.”

“I won’t,” promised Merry.

It hadn’t been easy, though, and Merry had already spent three months in the office, typing for Uncle George, when the sad news came that Aunt Ellen had died and bequeathed her Beau Ness, together with a small income.

Aunt Elizabeth had been furious, as she considered it a great mistake for Merry to have property of her own. The fact that Sylvia had twice inherited legacies made no difference, in her opinion. Besides, now that she was losing Merry, she was loth to admit that she would miss her, having found her willing and useful. Even George would find her difficult to replace, and would have to pay a trained girl a ridiculous salary for doing the same work.

“I suppose Sylvia is out with Graham,” said Merry, hoping to change the subject, and wishing fervently that the hands of the clock would move.

“Not an ideal choice of young man,” disapproved Aunt Elizabeth, “but dear Sylvia is so popular. I expect she feels sorry for him, though she’s much too beautiful to throw herself away on a mere schoolteacher.”

Merry felt a pang of sympathy for the earnest bespectacled young man who had once been her own boy-friend. He had so obviously fallen under the spell of her lovely cousin. Sylvia’s spun-gold hair fell round a pretty, piquant face with unusual slanting eyes. Her looks suggested a hidden depth and intelligence which Merry knew were both lacking. She’d never been close friends with

her cousin, who had treated her like a poor relation and who had sulked ever since Beau Ness became hers.

“Here’s the taxi now,” she cried, jumping up as wheels crunched in the drive. “Goodbye, Aunt Elizabeth ... Uncle George.” She bent to kiss their unresponsive faces. “Thank you for looking after me over the past three years. I ... I’ve appreciated having a home.”

The silence indicated that she had a queer way of showing her appreciation.

“Come and see me, won’t you?” she repeated.

“Sylvia will probably want to come, but we prefer not to travel during cold weather,” said her aunt. “Goodbye, Merry. I hope you won’t regret this.”

“Goodbye, my dear,” nodded Uncle George.

Merry ran down the steps of Fairlawn, the mode

rn

, expensive house which had sheltered her for those three years, and which had never seemed a real home in spite of all the luxurious thick carpeting and the most expensive and prettiest of furnishings. Beau Ness would be almost primitive by comparison, but already her heart was lifting as the taxi swung round at the gate, and into the main road. The journey ahead would take a good eight hours, and it would be early evening by the time she reached Kilbraggan, but Mrs. Cameron, the housekeeper, had promised to stay on and would have a warm fire

and

supper ready for her. Merry had known Mrs. Cameron ever since she was a schoolgirl.

“It will be a real pleasure, Miss Merry,” she wrote. “I was feared you’d be selling the house and we’d have another stranger among us. Rossie House has been empty since old Mr. Ross-Findlater died, and now there’s business folk living in it—the Kilpatricks from Hillington. Mr. Benjamin’s at the Cot House, too. I doubt if you know him, but he’s a funny one.

.

.”

Merry smiled as she sat in the Scottish train which would carry her straight to Glasgow before she had to change into a local train. She wondered what the Kilpatricks would be like, and Mr. Benjamin, the funny one, that being Mrs. Cameron’s favourite expression to cover anything that was odd. She spent the rest of the journey weaving delightful stories round his no

doubt strange appearance, and she hadn’t tired of the game when Joe Weir’s taxi finally deposited her at the door of Beau Ness.

“Mercy on us, Miss Merry,” cried Mrs. Cameron, hurrying to help carry her luggage into the house. “You’ll be weary to death of your journey. I’ve a pot of broth ready and you can sup a wee bit before you go to bed. I’ve put a piggy in the bed, though it’s been kept well aire

d

since

.

.. Oh, well, we’ll not be talking of that now.”

Merry nodded, too tired to say very much beyond the first greetings. She’d sup her broth because she knew she’d never be allowed into bed without it, but after that she’d be glad to crawl between the freshest of white sheets which always smelled of lavender.

It was wonderful to have Mrs. Cameron to fuss over her, and tuck her up in bed. She was hardly conscious of her leaving the room.

The following morning Merry awoke with a curious feeling of well-being. In one sense Kilbraggan was so quiet, but not in another, for the birds were singing joyfully, and not so far away she could hear the cows lowing in a field.

Merry lay quietly allowing the curious mixture of reality and strangeness to soak into her mind. This was Aunt Ellen’s bedroom, the biggest and most comfortable in Beau Ness, but Mrs. Cameron had been wise enough to move small knicknacks she’d always loved from the bedroom which had been hers. Now she lay looking at a favourite picture of a Highland loch; and reached out to fondle her china Scottie which now sat on the table beside her bed.

Merry lay remembering the long, carefree holidays she’d spent in Beau Ness when she and Aunt Ellen had roamed the neighbourhood together, coming in ravenous to eat Mrs. Cameron’s nourishing foods which were planned to put some beef on to Miss Merry. For a short time she allowed a few tears to trickle down her cheeks for the absence of Ellen Blayne, who had been her mother’s very dearest friend, though it was not a complete absence. It seemed as though the spirit of the older woman still lurked in quiet

corner

s, watchful of the fact that her beloved house was still cared for, and loved, its warmth still being used as a real home.

“That’s what it is,” said Merry aloud. “A real home.”

The first home she’d had since she was twelve, she thought happily, and in a mood of exultation she slipped back the warm blankets and stood on the thick sheepskin rug by the window, gently pulling back the curtains. No one could call it a “braw” day, but although grey, the sky was calm without lowering black clouds scuddi

n

g across. Merry had seen Kilbraggan in all its moods, and knew that this was “no sich a bad day”

—

good enough, in fact, for her to go for a brisk walk. Soon she would have to get down to serious writing again, but she was pleased to give

h

erself a few days to settle in, and decided to fix the following Monday as her first working day.

Merry had had very little success so far, though she knew that only to the few does success come easily. She’d sold a few articles and one short story. Now she would like to try a full-length novel with, perhaps, a few more articles and short stories to send out, for more immediate results.

Aunt Elizabeth had disapproved of her writing, accusing her of wasting her time on rubbish, but Ellen had always encouraged her, putting on her large reading glasses to inspect her latest manuscript, and criticising it intelligently.

“This one doesn’t quite come off, does it, Merry?” she would ask, handing back a short story. “One of your characters ... Joe

Bell ... h

as behaved rather out of character, if you know what I mean. He would never suddenly go to the funfair, after avoiding such a thing all his life. You’ll have to give him a reason for going.”

Merry had choked down, her defence of the story, and had later admitted that Aunt Ellen was right.

“You’ve got a talent for making characters come to life, though,” the older woman continued. “We mustn’t waste that. I think you ought to spend some time on your writing while you’re here.”

Merry had done her best work while sitting at Aunt Ellen’s big desk in her small study. Now she hoped to work there more permanently. Her income would be sufficient to feed her, and pay the household bills, including Mrs. Cameron’s wages, but; she would have to earn her own pocket money, and even some of her clothing allowance, and she loved clothes.