A.D. After Disclosure: When the Government Finally Reveals the Truth About Alien Contact (8 page)

Read A.D. After Disclosure: When the Government Finally Reveals the Truth About Alien Contact Online

Authors: Richard Dolan,Bryce Zabel,Jim Marrs

There might be deathbed confessions from old soldiers, leaked documents dismissed as forgeries, desperate researchers trying to prove the existence of something like the “Manhattan Project,” and TV reporters chasing the story of the “White Sands Myth” in the desert.

Following the recovery of exotic technology at Roswell (technology not from our civilization), logic would dictate that the president organize an elite team, charging them with getting to the bottom of the matter. The responsibilities would be manifold: analyzing the technology and duplicating it if possible, forecasting the level of public panic in the wake of Disclosure, determining the level of vulnerability to industrial or financial interests, managing media and academia, ensuring secrecy from hostile nations, and certainly learning everything possible about these other beings.

The group’s existence would have to be kept secret, even from Congress. For once the rest of the world learned of America’s possession of such awesome technology, they would jealously demand to be a part of its harvest.

The available evidence points exactly to this turn of events. During the mid-1980s, a seven-page document surfaced mysteriously—almost certainly leaked from within the U.S. intelligence community—which purported to be a briefing memo prepared in 1952 for President-elect Dwight Eisenhower. It described the recovery of crashed UFOs and alien bodies, and referred to “Majestic-12” or “MJ-12” as the group responsible for managing the secret.

Ufologists have argued over the authenticity of this document, as well as many similar documents subsequently leaked. Yet, following the event at Roswell, Truman would have been negligent had he not authorized some kind of group to respond.

5

The documents list the names of the alleged members of MJ-12. They included: the director of the CIA, a man who helped organize the Manhattan Project, the head of the Air Materiel Command at Wright Field, the Air Force Chief of Staff, the Chairman of the National Research Council, the head of MIT’s engineering department and leading aircraft designer, the Executive Secretary of the new National Security Council, the Director of the Harvard College Observatory, the head of the CIA’s Psychological Strategy Board, the base commander of the Atomic Energy Commission installation at Sandia Base, and the Secretary of the Joint Research and Development Board. All of them together would be the group one would want to examine the reality of flying saucers, to examine

what happened at Roswell, except for one person: Harvard astronomer Dr. Donald Menzel. While it may seem reasonable to include an astronomer on a team to study presumed extraterrestrials, Menzel’s inclusion baffled UFO researchers. During the 1950s and 1960s, he was the world’s leading debunker of UFOs. For years, he maintained that UFOs were simply misidentifications of prosaic phenomena: stars, clouds, airplanes, balloons, etc.

6

This was surely true for some sightings of odd lights in the sky—people are fallible, after all. But many of Menzel’s so-called explanations of UFO phenomena were threadbare, even embarrassing. Yet, as a leading astronomer of his time, his presence in the debate prevented many other academicians from entering the field.

Menzel’s inclusion in the documents was odd. Were the forgers making a joke? His name raised doubts. The MJ-12 papers were volatile enough, and such doubts further undermined them. Then came the story’s twist.

UFO researcher Stanton Friedman—that dogged, inveterate burrower in government archives, that meticulously detail man—discovered that Donald Menzel had led a double life. Not even Menzel’s wife had known about it. It turned out that Menzel had been a prominent, classified consultant for the U.S. intelligence community.

Not just any part of the intelligence community, but the CIA and the code-making, code-breaking National Security Agency (NSA). This was when no one knew the NSA existed, despite its probably being the most powerful of the U.S. intelligence agencies. The spooks cared little about Menzel’s knowledge of the stars; they were more interested in another of his talents, for Menzel just happened to be a world-class cryptographer, an expert in codes and ciphers. In a 1960 letter to President-elect John F. Kennedy, he mentioned his Navy Top Secret Ultra Security Clearance, and his association with this activity for almost 30 years. He told Kennedy that he probably had “the longest continuous record of association of any person in the country.”

7

When considering that it just might come in handy to have a smart fellow who knows how to crack difficult communications, Menzel’s inclusion makes a great deal of sense. His stature as a Harvard astronomer was a bonus, enabling him to slap would-be academic conspiracy theorists firmly into their place.

If the MJ-12 documents really were faked, it would seem that whoever created them knew of Menzel’s intelligence activities and background. That would have been very rarified information. Or perhaps, as Friedman believed, the documents were real after all.

The term

Majestic

has been used occasionally in this book to describe the group charged with managing the many problems posed by these Others. This may be its actual name, or it may not. Either way, it is logical and reasonable that President Truman—not wanting to pass the buck—created it from the most trusted members of the U.S. military, political, and scientific establishment.

Once that decision was made and the group formed, a machinery was created and set in motion. Machinery that was so complex, so labyrinthian, and so powerful, that it became alive.

Choke Points

Threats and intimidation, such as those made on Frankie Rowe and others, are not the only ways to keep a secret. Management of the press is also critical.

By the early 1950s, the CIA had developed relationships with most major media executives in the United States. This does not mean something so crass as CIA agents telling executives what to print or broadcast. Rather, it means that some executives voluntarily killed stories that would damage perceived American interests. Sometimes, when necessary, the CIA would be consulted. Sometimes stronger medicine was prescribed, like planting disinformation or even stories that were flatly untrue.

Even a partial list of the participating organizations is breathtaking: the

New York Times

, the

Washington Post

, the

Christian Science Monitor

, the

New York Herald-Tribune

, the

Saturday Evening Post

, the

Miami Herald

, Hearst Newspapers, Scripps-Howard Newspapers, and Time-Life. Major news wire services, such as Reuters, the Associated Press, and United Press International, also cooperated. So, too, did television and radio broadcast concerns such as CBS News, the Mutual Broadcasting System, and others. In addition to these, the CIA owned many newspapers and publishing houses overseas.

Some of this information came out during the 1970s, when the CIA admitted to having paid relationships with more than 400 mainstream American journalists.

8

Consider the possibilities available to any person or group covertly employing 400 journalists. Although the CIA claimed it ended such relationships, it tacitly acknowledged the need to cultivate them in cases of national security. More recently, one inside military source told the authors that CIA influence among freelance journalists today is “pervasive.” Former CIA Chief William Colby, a cold man who made his mark during the murderous Project Phoenix, who rose to the top of the Agency during the 1970s, and whose life ended in a boating “accident” on the Potomac in 1995, once told a confident that every major media was covered by the long reach of the CIA.

But the CIA sought to manage more than the media. It also gained influence over the world of the intellectuals by funding all political flavors: those on the right, in order to promote American global interests; and those on the left, to wean socialist-leaning Americans away from Communism and toward an acceptance of “the American way.”

9

This also happened in the world of academia, which several studies have amply exposed.

10

The CIA’s management of information is deft. Naturally, one cannot control all journalists, professors, and independent researchers. However, one can create chokepoints of information guarded by leading figures. If some maverick publishes something dangerous, the appropriate CIA proxy at the

Los Angeles Times

or Harvard University makes sure to attack it, and if necessary ridicule it. It is always the nail that sticks out that gets hammered.

More typically, unwelcome stories were blocked from going national. Throughout the 20th century, the wire services, collaborating with the CIA, simply neglected to carry them. Today, in the 21st century, this happens to be one area in which there is potential to turn the tables. Now, local stories can be spread far and wide via the Web. In the future, this may prove to be a problem for the secret-keepers.

So far, however, a preponderance of power remains on the other side of the fence. In fact, the revolving doors connecting academia, journalism, and the national security community are openly acknowledged. An

abundance of intellectuals actively court the national security world. Why not, when the connections, prestige, and paychecks are so compelling?

As it happens, most UFO debunkers have been connected with the national security community. In this regard, Donald Menzel has already been discussed, but during the 1960s, a successor to Menzel was in the wings: Philip J. Klass.

11

Klass was no scientist like Menzel, but he was the Senior Avionics editor for the prestigious defense publication,

Aviation Week and Space Technology

. For more than three decades, Klass used any and all means to throw cold water over the idea of UFOs. Some explanations were astronomical, even to describe large objects that were tracked on radar. Some he quickly labeled as hoaxes, such as a 1964 landing case witnessed by a terrified police officer, in which ground traces were photographed and studied. Other explanations were more creative, such as “ball lightning” to describe an enormous structured craft hovering at treetop level. When these failed to impress, Klass plied the trade of the propagandist, often via ridicule, invective, and furious letter-writing campaigns to smear reputations.

Throughout his career, Klass was under widespread suspicion—not proven as of this writing—of being an intelligence community asset. That he lived in the Washington, D.C. area, had consistent and exceptional access to the mainstream U.S. media, and worked within the defense community made such suspicion understandable.

People such as Menzel, Klass, and their successors have been important as vocal, media-savvy debunkers who seem independent, but are actually tied to the defense and intelligence community. Their work sets the tone for the mainstream media, which generally follows along happily.

Denial and Ridicule in Service to the State

Today, most professors and journalists—who have nothing to do with the national security state—have internalized the sanctioned opinions. They have learned to discuss UFOs the way a weary parent chastises a child for reading too many comic books. These things are not real. If you speak about them too much or too openly, people may think there is something wrong with you.

That is one reason why the cover-up has stood for so long. Had we followed our own glasnost policy from the beginning, the UFO argument would be over. People would have discussed this problem in the editorial pages, on the nightly news, and over hot dogs at their children’s ball games. They would have concluded that something was there. Except that the architects of the cover-up stumbled upon the twin concepts that enabled them to hide the truth from the people they were sworn to protect. Two pillars, each one lending strength to the other in service of the common goal.

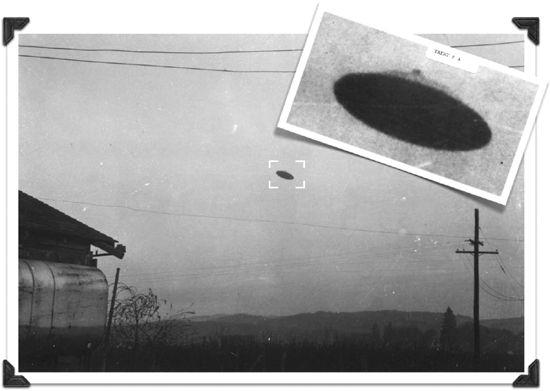

Denying the witnesses. People who saw “flying saucers” were often marginalized and ridiculed. One of the two famous McMinnville Photos from May 1950, strongly believed to be authentic

. Photo by Paul Trent.

Denial and Ridicule

Official denial works. When a general or leading scientist explains there is no fire, that the smoke is an illusion, our natural instinct is to believe—despite what the crazy neighbor thinks, sometimes despite the evidence from our own eyes. We want to believe our authority figures.

Ridicule gives denial its power. When official statements are made, language is of the utmost importance. It is easier to smirk at a “flying saucer” than an “unidentified flying object” or “unknown aerial phenomenon.” It is easier to dismiss alien intelligence when it is characterized as “little green men” instead of “extraterrestrial biological entities.” Alien agendas can be dismissed when boiled down to science-fiction scenarios in which the occupants land on the White House lawn and declare “take me to your leader.” Even the apparent widespread abduction of innocents has become the subject of ridicule on comedy shows. Even today, questions about the subject are often presented simplistically, often with a derisive sneer: “Do you believe in flying saucers piloted by little green men?” Imagine saying yes to that question.