Adventure Divas (22 page)

“Bachendri,” I ask, excited, “are there fish in this part of the river?”

“Yes,” she says quietly, then adds, “It is written in our sacred texts about the purity of the water. People worship the Ganges.”

Figures. There are fish. But the river—definitely sacred.

I ask Bachendri about her draw to Everest. She’d had a love affair with the Himalayas throughout her youth, but the big mountain must have been special. “When I first saw Sagarmatha [Everest], I bowed my head in reverence,” Bachendri says as we turn up a trail and start our ascent.

“Did you think you would summit?” I ask, trailing her, my eyes on her sneakers.

“No. I was not sure. But I was confident about my physical condition, and mentally I was very strong,” she says matter-of-factly.

On Everest, she faced that moment every climber fears: avalanche.

“It was midnight and I was sound asleep. I was hit on the back of the head suddenly, by something very hard. And I heard a very loud explosion, so then I realized there was a very big avalanche, and I was really waiting for the death, and I thought, ‘I am going to die. I am going to die.’ ”

Bachendri’s limited English has conveyed the shorthand version of a harrowing experience. At twenty-four thousand feet, she and nine others in her climbing party were sleeping in their tents when they heard a thundering sound from the glacier above them. Enormous tumbling blocks of ice and snow developed into a massive avalanche that rumbled down the mountain and buried Bachendri alive in her tent. Fortunately, she was dug out by one of her fellow climbers.

“I was carrying a small image of goddess Durga-Narishakti.

Nari

means woman,

Shakti

means power. Woman power,” Bachendri tells me.

“But aren’t you supposed to carry a very light load?” I ask, knowing climbers are religious about every ounce they pack. “And you carried a goddess up there?”

“Yes,” she says, laughing quietly, for the first time sweeping away a bug.

My arms have been moving constantly to keep black biting gnats at bay.

In the book

Leading Out: Stories of Adventurous Women,

Bachendri describes what the deity meant to her on the climb: “Well before dawn we began to dig out our equipment. I was terribly worried about the image of Goddess Durga which I had in my rucksack.”

Durga, as I learned back in Delhi, is worshipped as an embodiment of female energy. She takes different female forms and goes by many names; one of them is Kali.

“Every morning and evening I took it out and drew inspiration and strength from it. So my first act on finding my rucksack was to thrust my hand into the side pocket. To my relief my fingers encountered the ice-cold metallic image. I held the holy image tightly and, placing it on my forehead, felt that I had everything I wanted. I had Shakti in my arms—the Shakti which had saved my life a few hours earlier and the Shakti which, I was sure, would lead me onwards and upwards. The experience of the night had drained all fear out of me.”

Miraculously, nobody was killed in that avalanche, but Bachendri explains that the team, injured and in shock, was in disarray. When the rescue crew arrived the next day, most of her team returned to base camp, abandoning their bid for the top. Bachendri took another route.

“ ‘So what do you want to do?’ I say to myself. I am alive after this life-and-death situation. So I said, ‘I must try.’ And that decision was the turning point,” she tells me. Shaken yet determined, she kept climbing.

“I was literally on top of the world,” she says of her summit on May 23, 1984, with climbing partner Ang Dorjee. After digging their ice axes in for security, Bachendri reported of her summit moment, “I sank to my knees, and putting my forehead on the snow kissed Sagarmatha’s crown.”

Writer Alain de Botton explains how places such as the top of the world compel you to hit your knees: “Sublime places repeat in grand terms a lesson that ordinary life typically introduces viciously: that the universe is mightier than we are, that we are frail and temporary and have no alternative but to accept limitations on our will; that we must bow to necessities greater than ourselves. This is the lesson written into the stones of the desert and the ice fields of the poles. So grandly is it written there that we may come away from such places not crushed but inspired by what lies beyond us, privileged to be subject to such majestic necessities. The sense of awe may even shade into a desire to worship.”

Bachendri’s reverence in the face of success is refreshing compared to the bawdy swaggerers we get so much of in the media of today’s “extreme” sports. Competition and goal orientation too often muffle the subtler glories.

“Did you enjoy the climb?” I ask. Except for the summit, it sounded like a miserable experience.

“After coming back,” she admits, with a laugh.

Bachendri Pal’s 1984 Everest summit was a beginning. “After that I wanted to promote adventure sport among youth and women. Why not rural women? Rural women work very hard. Adventure should be a part of everyone’s life. It is the whole difference between being fully alive and just existing,” she says. With the public support of India’s then leader Indira Gandhi, Bachendri began to put her philosophy into action.

“The biggest hazard in life is not to take risk,” she continues, offering me some water before taking a small sip from her canteen. “If you want to achieve something you have to take risk. One of my big dreams was to lead an all-woman expedition up Everest.” Bachendri accomplished this in 1993 with several young rural women from her own home village. I notice she tells this story with considerably more pride than that of her own, first Everest summit.

We are both panting now, and say less. The modest summit of this baby Himalaya is about a hundred yards in the distance. We scramble upward, and I am recharged by the burn in my thighs. For the first time in weeks the quease in my stomach is gone; I do not feel unmoored. We are scrambling, without ropes or protection, but I feel anchored.

“Do the mountains feel . . . holy to you?” I ask.

“Oh yes, yes,” she says switching to Hindi, as if this is a question that can only be answered in one’s native tongue. “I really worship the mountains. I consider the mountains an ideal. Mountains offer self-discovery; a chance to understand our limitations and to understand our strengths.”

The natural world as a place to look inside and worship makes sense for the secularly minded like me; and the out-of-doors is a reasonable, inspiring temple. There is no overarching institution susceptible to human foible involved to muck things up, and no pearly-gate fantasies are required. It is a sure bet that in the final chapter we will all be communing with mother earth. Ashes to ashes and all that. Worshipping what we

know

to be our final destination makes some real sense to this rational Western mind.

We reach our small summit and in the distance we can barely make out giant, sharp, lumbering mountains, the kind that make you hold your breath, feel tiny and unburdened and excited all at once. Up here, in the temple of my familiar, the sacred doesn’t feel scary, and surrendering to it doesn’t feel like weakness.

“What do the mountains teach you?”

“My potentials. They teach me to believe in myself—to look up, and look straight in your life. With guts of great, and confidence,” she says with stumbling, yet no less profound, English. “That is very important whoever you are—an officer, an administrator, an engineer. To have that confidence, that gives you tremendous self-respect. I think nature is a great teacher and a great purifier. And that is why I look at every peak with respect. I revere them as my inspiration.”

For Bachendri the mountains are an “anchor.” And brawn, and rampant ego—a charge leveled at climbers the world over—seem absent from her approach. By insisting, with a quiet voice and a triple load of firewood, on chasing her own “potentials,” she got up Everest. She is a regular person who worked hard and summitted a mountain, and then parlayed that success into living her ideals.

I wonder how these unusual qualities, in this soft-spoken world-class climber, will translate to TV, a medium not known for subtlety. Bachendri ties the shoelace of her right sneaker, and lightly brushes dirt from the cuff of her pants. We take the descent in silence.

I jot down some thoughts

as we drive from Uttarkashi to Hardwar. We cruise down the switchbacks at double speed, gravity now on our side. I worry out loud about the challenge of capturing the complexities of India on the screen. “The good news is a picture tells a thousand words,” says Julie, ever tuned in to the upside of fate, and nodding toward our box full of shot film and tape. Except for the few rolls mysteriously destroyed in Mumbai, we’re not missing anything.

The Ganges flows out of

the Himalayas near the city of Hardwar, where we stand watching thousands of pilgrims dip in the holy waters. A constant chant bellows out over the dozens of tinny loudspeakers that line the river:

hey-beda, hey-be-da, hey-beda.

Even when the order of the day is reverence, the atmosphere is buzzing with energy.

In Cuba, you hear something before you see it; in Borneo, you feel it before you see it; in India, you smell it before you see it. Diesel exhaust. Crushed marigolds. Smoldering cow dung. Old hot cooking oil. Milky chai. And always, incense. The smells of India swirl around us. “We’ll need to make a scratch-’n’-sniff film to do this country justice,” notes Julie, handing me a chai.

Colorful porcelain statues of Shiva, Ganesh, Kali—practically the whole gang—perch in the water, the river parting around their brightly colored torsos. I snap a picture of Sky Prancer at the water’s edge. The plastic base from which she launches delicately divides the water just like the rest of the pantheon. In every direction there are people, pilgrims—orange, white, red, young, old, men, women, beggars, lepers,

sadhus—

all of them sweeping holy water onto their faces and over their heads, making

puja.

Bowls made of woven leaves and filled with marigolds, each centered with a white, softly flickering candle, float down the river as offerings.

This is a parade of worship as far as the eye can see.

Guts of great.

I think of Bachendri’s words as hundreds of people unself-consciously prostrate themselves to the unknown. To faith. Maybe finding the divine in the everyday simply lies in the service, devotion, and ritual we see in the divas, and before us now.

I bend down to launch my own boat-of-flowers offering into the Ganges, and feel something new climb on board. The boat floats off, and I stand and just watch the carnival of the sacred splayed out before me.

4.

SHORT-ROPED TO HEIDI’S GRANDFATHER

Climb if you will, but remember that courage and strength are naught without prudence, and that a momentary negligence may destroy the happiness of a lifetime. Do nothing in haste; look well to each step; and from the beginning think what may be the end.

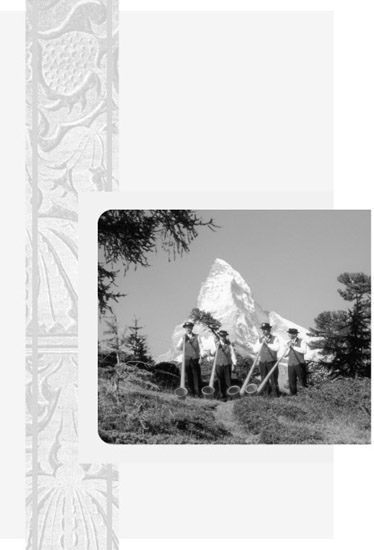

—EDWARD WHYMPER, CIRCA 1900

“

Y

eahhh, well, Bradley Cooper just pulled out of the Matterhorn shoot. Are you available?” says Ian Cross, over the phone from Pilot Productions in London.

Keeping up with Bachendri Pal on a day hike was one thing, but tackling the Matterhorn is another issue altogether. Bradley, a strapping lad of about twenty-five—the perfect television profile to conquer a classic mountain—is my male counterpart in the trekking series. He needed to be in Hollywood for auditions, and I had to decide if I could fill his shoes.

“The day rate is especially good since it’s a short shoot,” Ian says enticingly, noticing my hesitation. The QuickBooks data comes up with a single click of the mouse. I look at our Adventure Divas bank balance. Alarmingly few digits appear before the decimal point.

“I’d love to do it, Ian.”

“Bloody good then.”

Ian tells me about the rest of the production team, all guys, two Brits, two Americans, then we hang up.

This will be my first time, ever, working in an environment that is so X-weighted, chromasomally. The job will bring in a much-needed infusion of cash, but the experience of immersing myself in high-altitude mountaineering, a legendary bastion of maleness, could be the real sociological pay dirt. I start doing push-ups and prepare for a new kind of cultural exploration.

Twelve days later, as my ice ax is being confiscated at Sea-Tac airport, I make last-minute cell-phone calls before boarding a Boeing 777 to Heathrow, and then Zurich. Ever since a flash-flood scare while shooting a canyoneering show in Arizona, I have taken to calling loved ones prior to departure. Road life is tough on relationships. Cell phones help.

“Dad,” I say, walking down the gangway, “just wanted to say good-bye. I’m kind of worried.” He’s the right person to talk to. My lust for action comes from him, and he’s been a strong supporter of Adventure Divas and my business risks (if a bit bewildered by their estro-focus). Competition. Male-dom. These are the NFL’s human resources (and his) and what I might be tangling with on the mountain.

“Well, lots of people have climbed it,” he says by way of support, but I only hear the challenge. “I saw it up close once on a tram,” he adds.

“One thing’s for sure, you’ll never look back as an old woman and regret not experiencing the world,” he says, almost whimsically. “Call me when you get back, baby. Good luck.”

In order to acclimatize,

and add another element besides the Matterhorn climb to the program, we are scheduled to spend three days “warming up,” climbing around the Brenta, the Dolomites’ stunning mantelpiece of limestone spires and towers. The shoot begins on a sunny August day in the Dolomites’ jagged Via Ferrata (“Iron Route”), which rests in a stretch of mountains in the northeast of Italy. The team spends two days in a hotel at the base of the Brenta before the climbing begins. The team consists of Keith, who just lost twenty pounds filming on K2; Digger, a seasoned climber with guiding credentials galore and a new baby (not with him); a Tall Blond Quiet Man named Paul, who is a seven summits veteran and perhaps the most

deeply

mountain among us; and dark-haired, medium-build director Ben, who I have not figured out yet. Quiet Thirsty Girl may be their impression of me, as I drink glass after glass of water in the hopes of staving off a bladder infection.

We sit together in the dining room surrounded by very coifed Italians whose lipstick and nail polish match. We have had several meals together, yet an awkward silence lurks at our table like a giant, boring, clay-blob centerpiece. We have dissected every technical aspect of our forthcoming climbs, three times, and now grope for things to talk about. I keep thinking this stilted atmosphere between us will crack, and a “joie de road” will hatch. After all, three of the five of us—Digger, K2, and TBQM, that is, the

real

climbers—already know and like one another well. A paid work trip like this can only be gravy for them. They should be having fun. This is the first all-male team I have worked with. I look around at the guys and wonder about communication, or lack thereof. My years in feminist publishing lent themselves to overprocessed meetings, perhaps, but hardly ever silence.

Maybe this is normal?

“What kind of cheese is this?” TBQM asks, revealing a new twinkle in his eyes. I file away “cheese” as a topic we could pursue at our next meal together.

We hem and haw, and snap long, thin Italian breadsticks over the white linen tablecloth until finally, after much awkwardness, we stumble on a topic we can all engage in: a sunken submarine. CNN is reporting that a Russian nuclear sub has plummeted to the deepest part of the Barents Sea with a crew of more than one hundred on board. “Can you

imagine

what’s going on in their heads?” says Ben. “God, and the pressure.”

We have found something besides the climbs at hand, or climbing in general, to chew on. The submarine situation speaks to basic human fears and tragedy. We share a dark intrigue about the

Lord of the Flies

scene that might be taking place fathoms below. I wonder whether the sailors, when they took off from shore, had thought of it as a job or as an adventure.

Most likely the former. The sailors down below are poorly paid family men from a country with a dashed economy. We are affluent folks who endure risk, even chase it, for what must be entirely different (and often elusive) reasons.

“Everyone have extra beeners?” asks Digger before we set off the next morning. Everybody nods. Each person on our team—director, talent, camera—gets a “guide” to cover him or her mountainside. Digger covers Ben; Paul, a.k.a. TBQM, covers K2, and my guide is a local expert named Pierre Giorgio. Pierre Giorgio is a lean, dark Italian who, like many of his colleagues, comes from a long line of mountaineers.

With stumbling, earnest English, a genuine love of the mountains, a fuchsia cell phone that matches the piping on his outfit, and the balance of a tarantella dancer, Pierre Giorgio leads us through the Dolomites with the style of, well, an

Italian.

The jutting rocky peaks of the Dolomites are a majestic playground for any mildly competent mountaineer. The towers of rocks were once a coral reef that was exposed by a receding ice age. Among the climbing routes ten thousand feet above sea level you can find fossils of prehistoric sea creatures. The Via Ferrata is fully “protected,” meaning a climber can always be tied or clipped in; no free soloing necessary. The routes were originally developed by troops in World War I who used their considerable alpine skills to advantage during battles. Later, the routes were improved by mountaineers who wanted to shorten the time it took to get to popular climbs in the Brenta Dolomites. The result: magnificent climbs protected with cables, ladders, and fixed pitons, making otherwise dangerous terrains accessible.

Carabiners, or “beeners,” are our best friends as we traverse the Via Ferrata. At any given time one or two active carabiners are clipped from the harnesses around our waists into the fixed protection. The climbing is not technically difficult, but it demands stamina and a steely stomach in the face of sheer, brutal drops and great heights. I never could relate to Jimmy Stewart as he teetered miserably at the top of a bell tower in

Vertigo.

However, the frequent waves of queasiness that roll through my abdomen tell me that scampering at these heights is an unnatural act for the human animal. After all, we have soft feet and big brains—rather than, say, hard cloven hooves deft at negotiating jagged stone and mountain-goat-size brains that don’t dwell on cosmic hazards such as mortality and self-actualization.

“Vun clip eez okay here,” Pierre Giorgio says when there is only a thousand-foot drop. Later the fog rolls in and I cannot see the five-thousand-foot drop that lies below the four-inch ledge we are negotiating.

“Two clips here at all times,” Pierre Giorgio urges. He suddenly looks less relaxed. A new tendon defines his neck. A gap in the icy fog opens, but it does not reveal a crisp, heavenly view. Instead, I get a glimpse of the hellish abyss below.

“O mio dio,”

I say to Pierre Giorgio, repeating a phrase I picked up from him.

“

Due

cleeps,” he reiterates with a smile.

“Don’t look down, don’t look down, don’t look down,” I create a mantra, and think about Sky Prancer. She is currently wedged at the bottom of my backpack. If I spun her off this ledge, she would sail, arms up, blue tutu billowing around her chest, twirling for minutes . . . down, down, down in graceful circles until she plummeted into the rock thousands of feet below, shattering to bits. We’d have to erect a plaque in her honor. “Sky Prancer: She died hiking up much more than her skirt.”

I sing “Edelweiss” to distract myself until the tune inadvertently morphs into Tom Petty’s “Free Fallin’.” I stop singing.

A group of three young and brightly Gor-Texed guys climb up quickly behind me to pass.

Shame spiral!

Oh, to be passed on a route! I check that the carabiners are soundly clipped to my harness and to the steel rope, then plaster myself, bladder first, flat against the fifteen-million-year-old sedimentary rock. In the ruckus my nine-dollar gas-station sunglasses go sailing down down down and meet the fate imagined for Sky Prancer. The men scuttle around me

—grazie bella—

and zoom ahead

unclipped.

Well! I shoot a glance to Pierre Giorgio. “Spaniards,” he says, as if that is an explanation.

A perhaps obvious, but noteworthy, word about ropes and clips and other forms of “protection.” One might think from afar (as did I before I began to climb in college, and later for television) that they offer some sort of

help.

They do not. “Ah, well, at least we won’t be free climbing,” I used to naïvely think as I trailed a zealous college pal up a 5.7 route, or was asked to do a standup from a precipice with massive exposure. True, if your body is about to hurl off a cliff, protection will stop your fall, eventually. But does it make it any easier to climb? No. Does it change the psychological component? No. Hedge fear? No. As when using other forms of protection in life, the rigor, the glory, the emotional drama is always present. Protection, in climbing as in the bedroom, curbs the consequences of a misstep, to be sure, but our hearts pay little heed to it in the heat of the moment.

We huff and puff and struggle up Scala degli Amici

—

the Ladder of Friends—a rusty iron sixty-seven-rung ladder that is bolted to a sheer cliff. To distract myself from what is the region’s most dramatic drop, I tick off the names of all the Von Trapp kids: Gretl, Fredrich, Brigitta, Marta, Louisa, Kurt . . . damn, there’s one more. Louisa, Brigitta, Friedrich, Marta, Gretl, Kurt. Hmmm. A rung suddenly snaps under my left leg, which slips and flails unanchored into the universe. Both carabiners lock in under the pressure of my weight

—clllaaang!

“Caaareful,” says Digger, and I scramble up to the next rung, my heart pounding. I’m embarrassed that the camera is catching my every struggle (though admiring of K2, who also has to get up these heights ten steps ahead of me—all the while filming—in order to do his job). At the eleventh hour of this, our second day, my legs quivering, I try to remember that each hard step now will better my chances of getting up the Matterhorn next week; that each blister that is born, pops, and calcifies in my stiff new blue suede mountaineering boots will toughen me up for the

real

challenge . . . and that each ibuprofen taken now is one less I will have later. These thoughts, along with endless spectacular vistas and a deep need to outrun my own fermented stench from consecutive sweaty days

sino

shower, keep me at a steady pace despite the pain.

“One more hour, yes,” Pierre Giorgio says, also noting that moment when day gracefully downshifts toward evening.

A hut system that offers spare, communal accommodations to dozens of climbers is smattered across the Dolomites and links one day to the next. Before dinner I have bent myself into one of the stacked, narrow bunks and am cleaning out raw blisters when I overhear my colleagues outside the hut’s glassless window making bets about whether or not I will make it up the Matterhorn. Odds are even, apparently.

“Yeah.” “No.” “Well, it’s going to come down to her state of mind.”

Why the mediocre expectations? My inexperience? Would they be laying bets if I were a guy?

I slip into a quiet, lonely funk.

I hide my irritation as we carb up on piles of pasta puttanesca at long, narrow wooden tables. No freeze-dried stroganoff in these Italian Alps. I jab and twirl the noodles, and say little throughout the meal. At other tables tiny but indelicate glasses of grappa slosh with revelry before going down. My colleagues are experts at sussing out their clients, and it is now clear that this climb in the Dolomites is as much to observe my skills and whip me into shape as it is to add a story to the show. There are four possible outcomes of a Matterhorn climb: injury/death, client quits, the guides “call” the climb due to dangerous conditions or a failing client, and a summit success. I am too tired for anger, but a renewed determination to get up that mountain gestates inside, like an alien.