Adventures of a Waterboy (32 page)

Read Adventures of a Waterboy Online

Authors: Mike Scott

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Composers & Musicians, #Music, #Individual Composer & Musician, #Reference

Philip Tennant, meanwhile, had hustled me a deal with BMG, one of the few record companies I’d never been with (all I needed was Warner Bros and I’d have the set). The guys who signed me were a Swedish A&R man called Per and a wily old label boss called Harry McGee, no relation to Alan, known in the business as ‘the silver fox’. Per and Harry thought they were getting Mike Scott and were gobsmacked when halfway through negotiations I told them

A Rock In The Weary Land

was going to be a Waterboys album.

This was no light decision; I’d thought about it for three years. I’d come to detest the idea that there was some difference between Waterboys music and Mike Scott music, and I recognised that only by using the better-known name could I gather it all under one banner. Then there was the size of The Waterboys’ audience, several times larger than I commanded as a solo singer. And thirdly, most of all, I missed the alchemy of the name, the sense of being part of something bigger than myself, with band members who had the status of fellow Waterboys, not just backing musicians. So in the summer of 2000, as the release of

Weary Land

approached, I assembled a new Waterboys. And in the same way that I’d created the original band by selecting musicians who’d played on that era’s album,

A Pagan Place

, so this line-up comprised three players who’d worked on

A Rock In The Weary Land

: Jeremy Stacey, Livingston Brown and a new keyboard player, Richard Naiff.

Richard was one of those rare musicians who’d come to my attention, like Steve and Anto, through my hearing them by chance and wondering, who the hell is

that

? I was working in Maison Rouge late one night when the liquid tones of David Bowie’s ‘Lady Grinning Soul’, a favourite song from my teens, floated from a room down the studio corridor. The original had been played by the great Mike Garson, an avant-garde jazzer shoehorned into Bowie’s Spiders From Mars in 1972 in an inspired piece of cross-cultural casting by David and his bandleader Mick Ronson. Surely it couldn’t be! I walked down the corridor, stuck my head round the door and caught a glimpse of a bearded young guy, not Garson, hunched at the piano, a river of sound spilling from his blurred hands.

I didn’t want to interrupt so I asked my assistant engineer to run in when the music stopped and get the guy’s details. At the end of the evening I was handed a scrap of paper bearing the scrawled name Richard Naiff and a north London phone number. Next day I called Richard and invited him to come and record with me. On the appointed day he turned up at the studio, not looking much like anyone’s idea of a rock’n’roller. Thickly bearded, walking with a Monsieur Hulot bounce, clad in a patterned woolly jumper and with an extremely shy, self-deprecating manner – no eye contact whatsoever – Richard was more like a librarian than a rocker. I asked him what bands he played with and he replied, looking at the wall behind me, that he only did a few part-time gigs. ‘What do you do the rest of the time then?’ I said. ‘Oh,’ he told the wall in hesitant, embarrassed tones, ‘I’m working in a library.’

I’d found myself a real live talent in the raw: librarian or not, when Richard played he could turn his hand to anything. High melodic beauty? No problem, mate. Thundering storms of chordal passion? All in a day’s work, guv. Classical intros played on an outrageously distorted Hammond organ? House speciality, sir.

Most of the keyboards on

Weary Land

had been played by me or Thighpaulsandra, whose day job with the druggy British band Spiritualized precluded him from touring with The Waterboys. But as Richard’s version of ‘Lady Grinning Soul’ suggested, my new discovery was able to master whatever musical parts were put in front of him; he just needed the sounds that had been used on the album and his fingers would do the rest. So Richard’s first task as a neophyte Waterboy, a week before our tour commenced, was to make a pilgrimage to Thighpaulsandra’s remote Welsh farmhouse, commune with the prog-rock elf, and transfer the crucial sound samples into a travelling keyboard module.

Richard and a mate set out in an old banger. They journeyed through the West Country, over the Severn Bridge and deep into Wales until they reached Thighpaulsandra’s lonely farmhouse, high on the side of a hill. Like me, Richard was expecting to meet an Elvish wizard and he too was surprised to be greeted by a softly spoken Welsh gentleman. But once in the house, things turned strange. The lights were dim, the curtains were drawn and the temperature was dramatically high. Richard assumed this was because Thighpaulsandra lived with his mother, who was unwell, but as his eyes got used to the gloom he realised that slithering freely round the floor and walls, or poised unnervingly still on the arms of chairs, were numerous geckos and lizards.

Thighpaulsandra acted as if it was absolutely normal to live in perpetual twilight with a crowd of reptiles and made Richard a cup of tea. Then they went through to the music room, Thighpaulsandra leading the way while Richard loped behind, followed by several scurrying lizards, to find himself in a dark chamber filled wall-to-wall with vintage keyboards and art-rock paraphernalia. He squeezed himself into a smidgen of space, plugged in and proceeded to download Thighpaulsandra’s Mellotron samples under the baleful eye of a gecko, motionless on a nearby shelf.

Keyboard sounds assembled, the new four-piece Waterboys gathered for a crash course of London rehearsals and a six-gig romp around Norway to warm up. This was the debut live outing for the

Weary Land

sonic rock music, and it took until the final couple of nights for us to fully gel as a band. Unfortunately our second show, a scrappy affair in a Bergen aircraft hangar, was reviewed nationally and the Nordic journalists were aghast at the difference in sound and personnel from the old band. ‘This isn’t The Waterboys!’ fumed

Aftenposten

and

Bergens Tidende

, two newspapers which a helpful native translated for us on a ferry midway across a fjord as we travelled to the next gig. But the scathing headlines only motivated the band and our last two Norwegian concerts, in a packed theatre in Oslo, were shot through with defiance as we began to hit our groove and catch fire.

A few days later we played to five thousand punters at the Glastonbury Festival, in a rammed Acoustic Tent with a set that was anything but: a maelstrom of electric guitar, fuzz keyboards and Mellotron powered by the funk-blown Stacey/Brown rhythm section. We hurled out half a dozen songs from

Weary Land

– ‘Let It Happen’ and ‘The Charlatan’s Lament’ our opening salvo – and recast totemic old numbers like ‘Savage Earth Heart’. Standing on stage with a multi-coloured whirlwind of noise wailing around me, I felt the power of playing under the Waterboys banner for the first time in a decade and sensed the sum of all my changes. I was the hoop dancer at last, moving between my worlds connected to everything The Waterboys had ever meant to me or the audience: adventure, passion, The Mysteries, musical brotherhood. And it was

right

.

Backstage I was surrounded by happy well-wishers. The Silver Fox slapped me on the back while Philip Tennant shook my hand, thrilled to have played a part in the return of The Waterboys. Paul Charles, the agent who booked the Acoustic Stage, told me ‘this one will run and run’. Fans appeared at the fence outside the tent shouting their congratulations, and I recognised one of them, a wild-faced chap with straggly hair, from another festival in another age, fourteen years before, reappearing like the spirit of Glastonbury past.

After gathering our stuff, the band clambered into a minibus to go back to our hotel. Slowly we drove through the mad midnight of Glastonbury, amid biblical crowds, past crackling bonfires and huge dance tents from which thundering bass grooves boomed apocalyptically across the blackness. I leaned back in my seat, Janette’s head on my shoulder, my ears ringing from the show, and wondered into the future. The Waterboys were back but I still had everything to prove. How would

A Rock In The Weary Land

be received? Would radio still play us? There were lost highways to recover, a Fiddler yet to return, and who knew what challenges and adventures ahead.

We passed the main gates of the Festival and reached the open road. I leaned over to kiss Janette’s head and smelt the womanful scent of her hair. Down the hill behind us the last bass notes were booming through the air, and as we sped through the night they faded until I could hear them no more, and the music in my head took over.

Appendix 1: Illustrations

Mike, London, 1972 (© Anne Scott).

Mike's mother, Anne Scott, c. 1969 (© Anne Scott).

Jungleland

fanzine, issue 6, November/December 1977 (© Mike Scott).

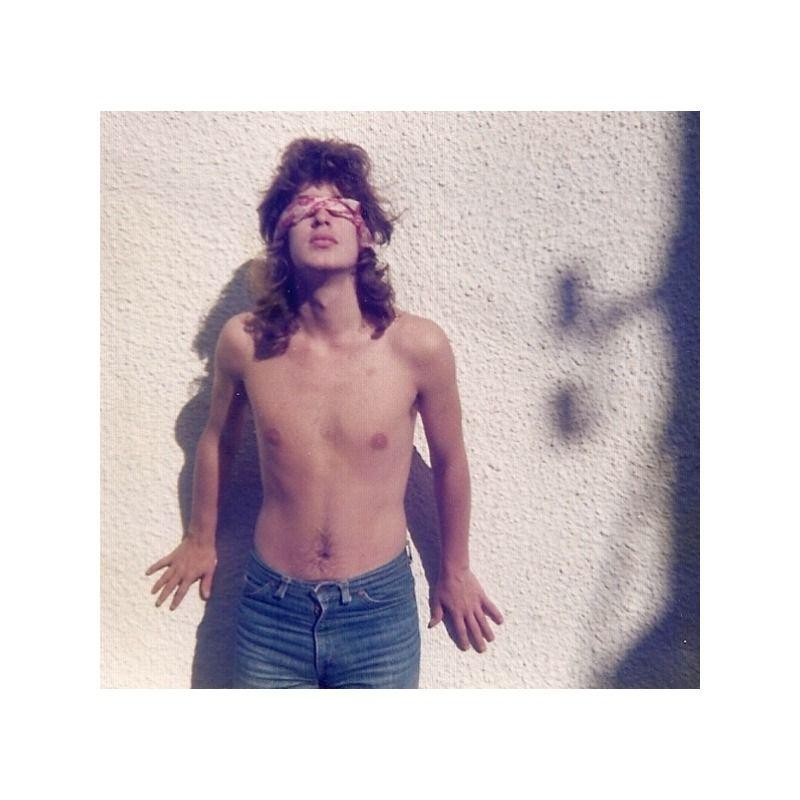

A Patti Smith pose, 1978 (© Mike Scott).

John Caldwell and Mike Scott, London, 1979 (© Ally Palmer).

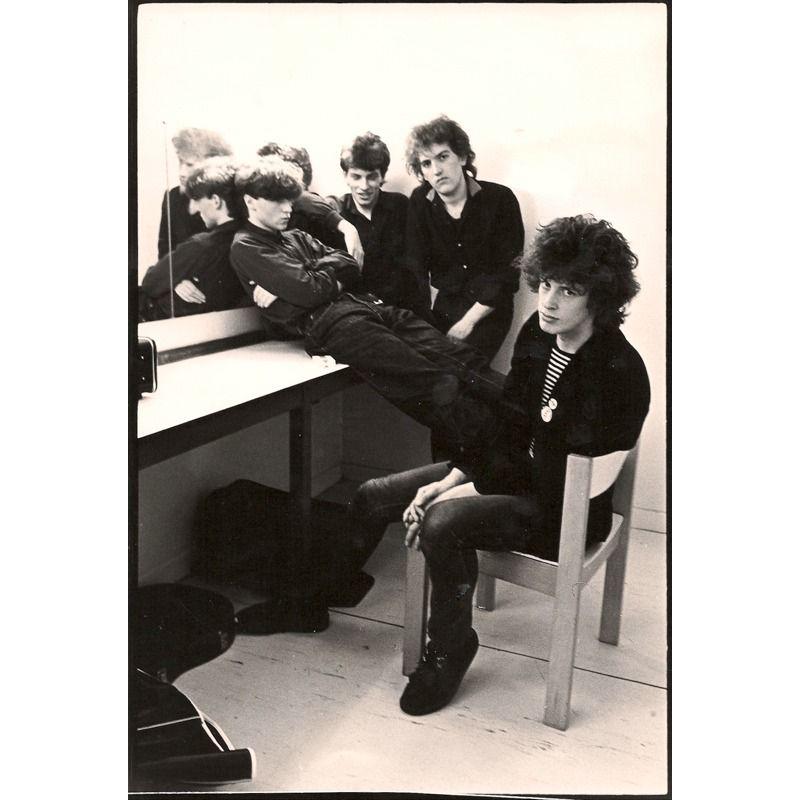

Another Pretty Face, 1979 (© Virginia Turbett).

A poster for APF's 'Heaven Gets Closer Everyday' single, 1980.

Mike, 1982 (© Jill Furmanovsky, rockarchive.com).

An advertisement for Mike's shortlived band The Red And The Black.

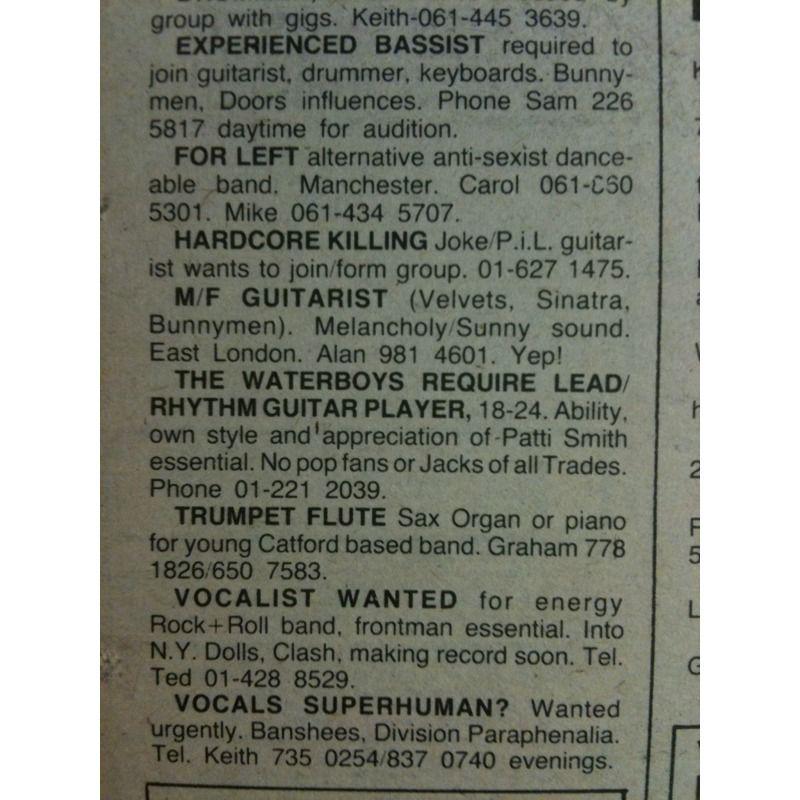

The NME ad to which Karl Wallinger replied, 1983.

The Waterboys on tour in the USA, 1984 (© Patrick Durand).

Legendary drummer Jim Keltner, 1986 (© Pete Vernon.

Steve Wickham and Anto Thistlethwaite at Mill Valley, California, December 1986 (© Mike Scott).

Steve Wickham and Anto Thistlethwaite, Werchter Rock Festival, July 1986 (© Philippe Herriau).