After Midnight (20 page)

Authors: Irmgard Keun

So Algin is planning to […] walk off into the Taunus, along the Mosel, going he doesn’t mind where. […] He hopes, even in Germany, he can earn enough as a writer and poet to sleep at an inn, eat bread and drink a glass of wine in the evening, without prostituting himself too much (119)

—but he abandons this resolve at his last appearance in the novel, partly because he is disoriented by Heini’s death (which I discuss below). Algin’s probable fate is foreshadowed in that of the sickly five-year-old Berta Silias, who collapses and dies after endlessly repeating the vacuous doggerel which her ambitious father wrote for her to recite while presenting a bouquet to Hitler during the Nazi leaders’ visit to Frankfurt:

A little German maid you see.

A German mother I shall be,

My Führer, and I bring to thee

The fairest flowers of Germany […] (41)

Herr Silias’s “poem about the Führer,” which kills his daughter, suggests that if Algin continues to write as the regime wishes he will debase himself artistically, and commit literary suicide.

As Heini’s repeated comments of course indicate, he

refuses to compromise with Nazism. This makes it almost impossible for him to keep writing in Germany, as Sanna notes: “Heini […] used to be a well-known journalist. He hardly writes at all these days—for political reasons” (75–76). And at Liska’s party, Heini recoils from the prospect of continuing his career outside Germany:

I’ve spent over ten years writing my fingers to the bone, racking my brains, to warn people of the madness of the barbarism ahead. A mouse squeaking to hold back an avalanche. Well, the avalanche has come down, burying the lot of us. And the mouse has squeaked its last. I am old and ridiculous: no power or desire to begin all over again. […] There are plenty of others to say the rest of what I would have said for me. […] You’ll find any other country is smooth and hard as a chestnut shell. You become a trial to yourself and a burden on others. For the roofs that you see are not built for you. The bread that you smell is not baked for you. And the language that you hear is not spoken for you. (142–43)

Moments later, Heini kills himself, apologizing “if I’m disturbing the party a little” (146) before he shoots himself in the head. Heini’s penetrating analysis of the Nazi regime’s iniquities, his haunting expression of despair at the regime’s victory, and his dramatic removal of himself from the regime’s control contrast starkly with Algin’s protracted campaign to secure the regime’s approval, and through them Keun creates a powerful figure of a writer who vigorously rejects fascism.

Nevertheless,

After Midnight

expresses its key judgments

about authors’ responses to the Third Reich through Sanna, most notably through her relationship with her fiancé Franz. Sanna and Franz are obviously important in purely human terms, as the only significant characters in the novel who do not allow their emotions to be corrupted by Hitler’s Germany, with Sanna remarking artlessly but affectingly at one point that “[i]t was only when I loved Franz I understood the world, and felt happy” (104). But the subplot which culminates in the young couple’s emigration also subtly evokes the issue of writing under Nazism in general, and subtly evaluates Algin’s and Heini’s decisions is particular. That subplot begins with Sanna and Franz’s plan to open a tobacconist’s store, which they hope will expand to include “newspapers and magazines and […] a little lending library” (61), and which their partner Paul hopes will sell “books and journals containing politically undesirable material” (128). After Franz and Paul are denounced on spurious political grounds by a commercial rival called Schleimann, and Paul is killed in custody, Franz is counselled by another storekeeper against fighting the Nazi system:

They took my nephew too, my nephew who helps me in the shop, and they kept him longer than you. He keeps quiet about it. He hangs out the swastika flag—well, you have to. We have to go along with it all, we want to live. They’re stronger than we are, you can’t do anything against them on your own. (133)

The man is an antiquarian bookseller, so that when Franz ignores his advice and kills the ex-Stormtrooper Schleimann, he symbolically disavows a conservative literary culture which survives by adopting the Nazi banner. The

murder of Schleimann prompts the young couple’s flight from Germany, for which Sanna equips Franz with Algin’s suit, coat and passport (147). Thus the would-be tobacconist emigrates as a surrogate for the artistically compromised novelist, in a further emblematic rejection of the literary profession as it is practised in the Third Reich.

While Sanna is packing for the journey in her bedroom during Liska’s party, and Franz is hiding in the basement of the building, Sanna is disturbed by the sound of the doorbell:

Perhaps they’ve already come to arrest Franz. Then I can stay here, it’s not my fault, I did all I could, all I could … Oh, I am a pig, a pig! God forgive me for my sins. I love you, Franz. Everything will be all right if we love each other and keep together. Perhaps we’ll die together. (144)

Sanna’s first thought here, that she can abandon her fiancé in good conscience because she did her utmost to save him and has now been overtaken by events, closely parallels Heini’s view (which he expressed only one paragraph earlier) that he can abandon his antifascist journalism because he fought Nazism for years and Germany has now been overwhelmed by it. This means that when Sanna promptly asks God to forgive her for that first thought and vows to stand by Franz to the death, the narrative implicitly reproaches Heini for his refusal to renew the struggle against Nazism from exile, and for his decision (which he carries out only two paragraphs later) to kill himself. And the narrative makes the contrast between Sanna and Heini explicit in the closing paragraphs, when Sanna and Franz’s train

crosses the border and she recalls, and resists, Heini’s bleak presentiment that:

“The roofs that you see are not built for you. The bread that you smell is not baked for you. And the language that you hear is not spoken for you.”

Franz’s arms hold me tight, his breath is a torrent of love. The train is not running on rails, it’s floating over a sea of happiness.

This seat is terribly hard and uncomfortable, but you are with me. We’ll sleep now. We shall need strength when we wake up. There are still stars shining behind the misty clouds. Please God, let there be a little sunlight tomorrow. (150)

But Sanna does not simply emigrate as a surrogate for the defeatist journalist Heini. She also expresses a cautious optimism about life in exile on behalf of the antifascist novelist Keun, and a cautious hope that

After Midnight

will shine a light on the darkness of the Third Reich.

We will never know if the echo of Sanna’s “God forgive me for my sins. I love you, Franz” in Keun’s own “God forgive me for my sins—but I really can write” was deliberate. But there can be no doubt that the repeated “Gott verzeih mir die Sünde” points to the ethical core and the artistic achievement of

After Midnight

. For Sanna’s fierce reaffirmation of her responsibility to help Franz unambiguously challenges her fellow Germans—and German authors—to defy Nazism in the ways open to them, and it presents that challenge with a power—and a subtlety—which demonstrate that Irmgard Keun really could write.

Editorial Note

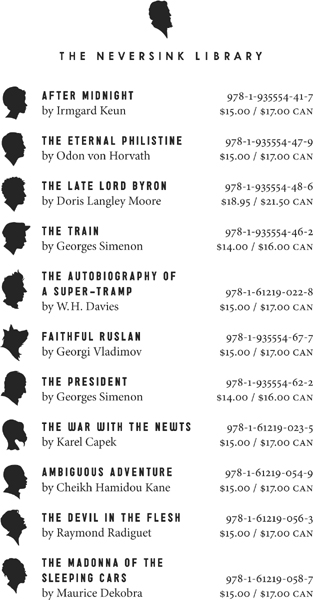

All quotations from

After Midnight

are from the Melville House edition.

The quotations from

Child of All Nations

are from the Overlook Press edition, Woodstock & New York 2008, 6 and 30–31. The translation is by Michael Hofmann.

The quotation from “Pictures from Emigration” is from Keun’s

Pictures and Poems from Emigration

, Epoche Press, Cologne 1947, 26. The translation is my own.

The quotations from Keun’s letters to Strauss are from the originals held by the Historical Archive of the City of Cologne. The translations are my own.

The quotations from Keun’s letters to Hermann Kesten and Heinrich Mann are taken from Stefanie Arend and Ariane Martin’s

Irgmard Keun 1905/2005: Deutungen und Dokumente

, Aisthesis Press, Bielefeld 2005, 297 and 305. The translations are my own.

The extant correspondence initiated by Keun’s attempt to sue the

Gestapo

is held by the “Stiftung Archiv der Parteien und Massenorganisationen der DDR” of the Federal Archive in Lichterfelde, Berlin, in the file R58/914. The extant file on Keun which was maintained by the Reich Literary Chamber is 2100/0458/18.

Kurt Tucholsky’s review of

Gilgi, One of Us

was published in

Die Weltbühne

on February 2, 1932, and Kurt Herwath Ball’s review of

The Artificial Silk Girl

was published in

Hammer: Blätter für deutschen Sinn

in September 1932. The translations of the brief quotations from those reviews are my own.

The quotation from Walter Benjamin’s “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” is from a collection of his essays published under the title

Illuminations

, William Collins Sons, Glasgow 1977, 243. The translation is by Harry Zohn.

Geoff Wilkes

University of Queensland

Brisbane, Australia