After Tamerlane (8 page)

Authors: John Darwin

although China, like much of Middle Eurasia, had felt the violent impact of Mongol imperial ambition, the blow had been softened. The steppe invaders had learned very quickly that they had to maintain the apparatus of imperial rule if they hoped to exploit China's agrarian wealth. They had to become âSinicized', corroding as they did so the tribal loyalties on which their power had been built. Mobilizing the south against the alien conqueror made it possible to maintain stable, continuous government far more completely than in Middle Eurasia, where Turkic tribes and military slaves were the main beneficiaries of political change.

But China's cohesion was not simply the consequence of commercial and strategic self-interest. It rested upon the achievement of a remark

able âhigh culture', a classical, literary civilization, whose moral and philosophical outlook derived from Confucian texts. Just as critical, perhaps, to the making of China as the junction of its north and south was the entrenchment of this Confucian learning in a literati elite and their recruitment to form an imperial bureaucracy. Once Confucian scholarship and literary skill (writing the âthree-legged' essay required by the civil-service examiners) became the ticket of entry into imperial service, they enjoyed the devotion of the educated class in every part of China. The adoption by the provincial gentry of literati ideals (and bureaucratic ambitions) was a vital stage in China's transition from a semi-feudal society, where power was wielded by great landholders, into an agrarian empire. What made that possible was an imperial system that relied much less on the coercive power of the imperial centre (a clumsy and costly option in such a large state) than on the

cultural

loyalty of the local elites to an imperial idea with which their own prestige was now closely bound up. As a formula for the exertion of effective power at very long range, it was astonishingly ingenious and astonishingly successful.

It was hardly surprising that the impressive scale of the Chinese state, the wealth of its cities, the skill of its engineers and artisans, the quality of its consumer goods (like silk, tea and porcelain), the sophistication of its art and literature, and the intellectual appeal of its Confucian ideology were widely admired in East and South East Asia. In Korea, Japan and Vietnam (parts of which were ruled as a province of China for over a thousand years until

AD 939

), China was regarded as the model of cultural achievement and political order. Chinese merchants had also developed an extensive trade, taking their products to South East Asia.

47

The seafaring and navigational skills of Chinese sailors â including the first use of the magnetic compass â were comparable with, if not superior to, those of their Arab or European counterparts.

Around 1400, it might have seemed to any well-informed observer that China's pre-eminence in the Old World was not only secure but likely to grow stronger. Under Ming rule, China's subordination to the Mongols and their imperial ambitions all across Eurasia had been definitively broken. Ming government reinforced the authority of the emperor over his provincial officials. The use of eunuchs at the

imperial court was designed to strengthen the emperor against the intrigues of his scholar-gentry advisers (as well as protect the virtue of his concubines). Great efforts were made to improve the agrarian economy and its waterway network. Then, between 1405 and 1431, the emperors dispatched the eunuch admiral Cheng-ho on seven remarkable voyages into the Indian Ocean to assert China's maritime power. Commanding fleets carrying over twenty thousand men, Cheng-ho cruised as far as Jeddah in the Red Sea and the East African coast, and made China's presence felt in Sri Lanka, whose recalcitrant ruler was carried off to Peking. Before the Europeans had gained the navigational know-how needed to find their way into the South Atlantic (and back), China was poised to assert its maritime supremacy in the eastern seas.

This glittering future was not to be. Instead, the early fifteenth century was to show that, while China was still the most powerful state in the world, it had reached the limits of oceanic ambition. There would be no move beyond the sphere of East Asia until the Ch'ing conquered Inner Asia in the mid eighteenth century. The abrupt abandonment of Cheng-ho's maritime ventures in the 1420s (the 1431 voyage was an afterthought) signalled part of the problem. The Ming had driven the Mongols out, but could not erase the threat that they posed. They were forced to devote more and more resources to their northern defence, a geostrategic burden whose visible part was the drive to complete the so-called Great Wall. Turning their back on a maritime future may have been a concession to their gentry officials (who disliked eunuch influence), but it was also a bow to financial constraints and the supreme priority of dynastic survival. The Ming decision reflected, perhaps, a deeper constraint. The Ming dynastic principle was the fierce rejection of the Inner Asian influence that the Mongol Yuan had wielded. It united China against the cultural outsiders. It asserted the exclusiveness of Chinese culture. A âGreater China' of Han and non-Han peoples was incompatible with the Ming vision of the Confucian monarchy. The grand strategy of indefinite defence carried with it the logic of cultural closure.

48

There was a further change, whose effects no contemporary observer could have fully grasped. The greatest puzzle in Chinese history is why the extraordinary dynamism that had created the largest

and richest commercial economy in the world seemed to dribble away after 1400. China's lead in technical ingenuity and in the social innovations required for a market economy was lost. It was not China that accelerated towards, and through, an industrial revolution, but the West. China's economic trajectory has been furiously debated. But the hypothesis advanced by Mark Elvin more than thirty years ago has yet to be overturned.

49

Elvin stressed the advances achieved by China's âmedieval economic revolution' in the Sung era, but insisted that when China emerged from the economic depression of the early Ming period (a product in part of the great pandemic) a form of technical stagnation had set in. More was produced, more land was cultivated, the population grew. But the impetus behind the technological and organizational innovations of the earlier period had vanished, and was not recovered. China grew quantitatively, not qualitatively. Part of the reason, Elvin argued, was the inward turn we have noticed already: the shrinking of China's external contacts as the Ming abandoned the sea. There was an intellectual shift away from the systematic investigation of the natural world. And it was partly a matter of exhausting the reserves of fresh land, so that less and less was to spare for industrial crops (like cotton) after the needs of subsistence had been met. A subtler influence was also at work. China was a victim of its own success. The very efficiency of its pre-industrial economy discouraged any radical shift in production technique (even in the nineteenth century, the vast web of water routes made railways seem redundant). The local shortages, bottlenecks and blockages that might have driven it forward could be met from the resources of other regions, linked together in China's vast interior market. Pre-industrial China had reached a âhigh-level equilibrium', a plateau of economic success. Its misfortune was that there was no incentive to climb any higher: the high-level equilibrium had become a trap.

50

We should not anticipate too much. It was to be more than three centuries before anyone noticed.

Eurasia and the Age of Discovery

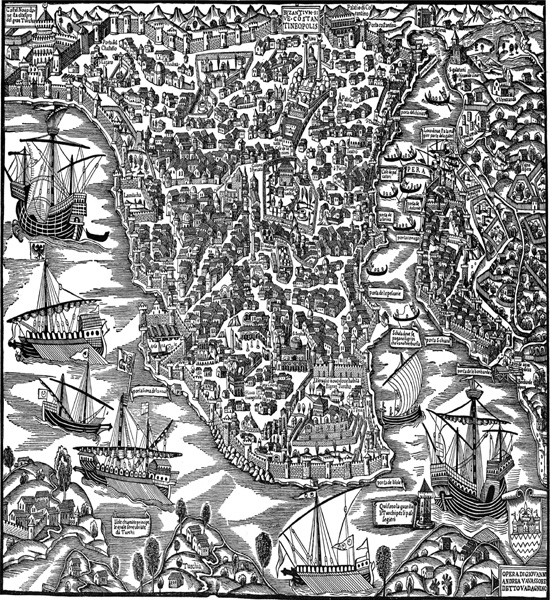

2. Constantinople in the mid-sixteenth century

In retrospect, we can see that the rough equality that existed between the three great divisions of the Old World was ultimately to be overturned by the events of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries â even if their significance was to be largely hidden from contemporaries. With astonishing rapidity after the 1480s, Europeans voyaging from Portugal and Spain transformed the geopolitical relationship between the Occident and the rest of the Old World. Europe was no longer the Far West of Eurasia facing out over the âSea of Darkness'. It had become by the mid sixteenth century an emerging entrepô t for the oceanic trade of the whole world, the headquarters of a maritime enterprise that now extended from China to Peru, and the point of departure for a new transatlantic zone reserved exclusively for its exploitation.

Yet it is also important to keep this great change in perspective. It was not inevitable that the âdiscoveries' should have led to Europe's global supremacy. We should not exaggerate the resources that Europeans mobilized for their voyages and conquests, nor mistake the means that allowed them to establish their footholds in Asia and the Americas. Least of all should we be tempted to read into the adventures of navigators and conquistadors a conscious design for a worldwide empire â even though Cortés tried to ingratiate himself with Charles V by claiming that Spain's American possessions were equivalent to the Habsburgs' European dominions. For all its drama, the Occidental âbreakout' of the long sixteenth century (1480â1620) had for long a limited impact. It depended heavily upon local circumstance and the gradual evolution of specialized subcultures of contact and conquest. It was not the working-out of an inescapable economic destiny (as some historians have argued), or the inevitable product of technological primacy.

One other temptation must be resisted. Europe's âcolonizing' history is often viewed in splendid isolation from the larger context of world history. It is as if from

c

. 1500 onward only Europe was dynamic and expanding: the rest of the world had ground to a halt. It is salutary to remember that, contemporaneous with the triumphs of Vasco da

Gama or Albuquerque in the Indian Ocean, or of Cortés and Pizarro in the Americas, were the consolidation of Ming absolutism, the emergence of a new world power in the Ottoman Empire, the reunion of Iran under the Safavids, the rapid expansion of Islam into South East Asia, and the creation of a vast new Islamic empire in North India after 1519. The significance of the discoveries must be seen against this larger picture of Eurasian expansionism: the Old World must be called in to balance the New.

The Portuguese were the oceanic frontiersmen of European expansion. The Portuguese kingdom was a small weak state perched on the Atlantic periphery. But by

c

. 1400 its rulers and merchants were able to exploit its one magnificent asset, the harbour of Lisbon. Europe's Atlantic coast had become an important trade route between the Mediterranean and North West Europe. Lisbon was where the two great maritime economies of Europe â the Mediterranean and the Atlantic â met and overlapped.

1

It was an entrepô t for trade and commercial information and for the exchange of ideas about shipping and seamanship.

2

It was the jumping-off point for the colonization of the Atlantic islands (Madeira was occupied in 1426, the Azores were settled in the 1430s), and for the crusading filibuster that led to the capture of Ceuta in Morocco in 1415. Thus, long before they ventured beyond Cape Bojador on the west coast of Africa in 1434, the Portuguese had experimented with different kinds of empire-building. Their geographical ideas were shaped not only by knowledge of the great Asian trade routes that had their western terminus in the Mediterranean, but also by the influence of crusading ideology.

3

Ironically, the crusading impulse assumed that Portugal lay at the western edge of the known world and that the object was to drive eastward towards its centre in the Holy Land. Perhaps it was this and Portugal's early forays into North Africa after 1415 (where it heard of Morocco's West African gold supplies) that pulled the Portuguese first south and east rather than westward across the Atlantic. The tantalizing vision of alliance with the Christian empire of Prester John (supposedly

lying somewhere south of Egypt) encouraged the hope of navigators, merchants, investors and rulers that, by turning the maritime flank of the Islamic states in North Africa, Christian virtue would reap a rich reward.

4

Prester John was only a legend, and so was his empire. Nevertheless, by the 1460s the Portuguese were pushing ever further south in search of a route that would take them to India â the goal triumphantly achieved by Vasco da Gama in 1498.

5

But it took more than navigational skill to carry Portuguese sea power into the Indian Ocean. Two vital African factors made possible their sea venture into Asia. The first was the existence of the West African gold trade that flowed north from the forest belt to the Mediterranean and the Near East. By the 1470s, the Portuguese had managed to divert some of this trade towards their new Atlantic sea route. In 1482â4 they brought the stones to build the great fort of San Jorge da Mina (now Elmina in Ghana) as the âfactory' for the gold trade. (A âfactory' was a compound, sometimes fortified, where foreign merchants both lived and traded.) It was a crucial stroke. Mina's profits were enormous. Between 1480 and 1500 they were nearly double the revenues of the Portuguese monarchy.

6

In the 1470s and '80s, they supplied the means for the expensive and hazardous voyages further south to the Cape of Storms (later renamed the Cape of Good Hope) rounded by Bartolomeu Dias in 1488. The second great factor was the lack of local resistance in the maritime wilderness of the African Atlantic. South of Morocco, no important state had the will or the means to contest Portugal's use of African coastal waters. Most African states looked inland, regarding the ocean as an aquatic desert and (in West Africa) seeing the dry desert of the Sahara as the real highway to distant markets.