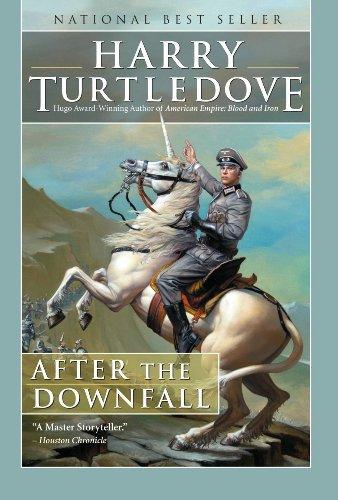

After the Downfall

Read After the Downfall Online

Authors: Harry Turtledove

Tags: #Science Fiction, #Fiction, #Short Stories, #Fantasy - General, #Fantasy Fiction, #Fantasy, #Fiction - Fantasy, #History, #Fantasy - Short Stories, #Graphic Novels: General, #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Science Fiction And Fantasy, #Graphic novels, #1918-1945, #Berlin (Germany), #Alternative histories

AFTER THE DOWNFALL

AFTER THE DOWNFALLHARRY TURTLEDOVE

After the Downfall ©

2008 by Harry Turtledove

Dedication

In grateful remembrance of Dr. Jorge Petronius (1963 - 2005).

I

Berlin was falling, falling in ruin, falling in fire, falling in blood. Back when the war was new, Goring said you could call him Meyer if a single bomb ever fell on the capital of the

Reich.

Had anyone held the

Reichsmarschall

to his promise, he would have changed his name a million times by now. Goring never said a word about shells or machine - gun bullets. Back in those triumphant days, who could have imagined Germany would go to war with Russia?

Not

needing to worry about Russia helped make the destruction of France as easy as it was.

And who could have imagined that, if Germany

did

go to war with Russia, she wouldn’t knock down the Slavic

Untermenschen

in six weeks or so? Who could have imagined that those Red subhumans would fight their way back from the gates of Moscow, back across their own country, across Poland, across eastern Germany, and into Berlin? Who could have imagined the war was over except for the last orgy of killing, and all the

Fuhrer’s

promised secret weapons hadn’t done a thing to hold off Germany’s inevitable and total defeat?

Captain Hasso Pemsel and what was left of his company crouched in the ruins of the Old Museum. The space between the Spree and the Kupfergraben was Berlin’s museum district. These days, the finest antiquities were in G Tower, next to the Tiergarten. People said the massive reinforced - concrete antiaircraft tower could hold out for a year after the rest of Berlin was lost. Maybe soon they would get the chance to find out if they were right.

A Russian submachine gun burped bullets. Behind Hasso, something shattered with a crash. It might have come through two or three thousand years, but a curator had decided it wasn’t worth taking to G

Tower. Nobody would study it any more - that was for sure.

Where was the Ivan with the burp gun? Pemsel spotted motion behind a pile of rubble. He squeezed off a short burst with his Schmeisser, then ducked away to find fresh cover. A wild scream came from the direction of the heap of bricks and paving stones. It didn’t lure him into looking. The Russians were past masters at making you pay if you fell for one of their games.

Like it matters,

Hasso thought.

You’re going to die here any which way. Sooner or later? What

difference does it make?

But discipline held. So did a perverse pride. He refused to do less than his best, even now - maybe especially now. If the Russians wanted his carcass, they’d have to pay the butcher’s bill for it.

A few meters away, his top sergeant was rolling a cigarette with weeds that might have been tobacco and a strip of paper torn from

Der Panzerbär. The Armored Bear

was the last German newspaper going in Berlin; even the Nazi Party’s

Volkischer Beobachter

had shut down. Karl Edelsheim was good at making do. Like Hasso, he’d been in the

Wehrmacht

since before the war, and he was still here after almost four years on the Eastern Front. How much longer he or any of the German defenders would be here was a question Hasso declined to dwell on. Instead, he said, “Got any more fixings? I’m out.” If you paid attention to what was right in front of you, you could forget about the bigger stuff... till you couldn’t any more.

“Sure, Captain.” Edelsheim passed him the tobacco pouch and another strip of newspaper. Hasso rolled his own, then leaned close to the

Feldwebel

for a light. Edelsheim blew out smoke and said, “We’re fucked, aren’t we?” He might have been talking about the weather for all the excitement or worry he showed.

“Well, now that you mention it, yes.” Hasso didn’t wail and beat his breast, either. What was the point?

What was the use? “Where are we going to go? You want to throw down your Mauser and surrender to the Ivans?”

“I’d sooner make ‘em kill me clean,” Edelsheim said at once. The Russians were not in a forgiving mood. After some of the things Hasso had seen and done in the east, he knew they had their reasons. Edelsheim had fought there longer. Chances were he knew more.

Another burst of submachine - gun fire made them both flatten out. They might have been ready to die, but neither one was eager. Hasso had seen a few

Waffen-SS

officers, realizing Germany could not prevail, go out against the Russians looking for death, almost like Japanese suicide pilots. He didn’t feel that way. He wanted to live. He just thought his chances were lousy.

Most of the bullets thudded into the wall in back of him. One spanged off something instead. The sound made Hasso turn around.

The

Wehrmacht

captain saw... a stone. It was perhaps a meter across, of brownish - gray granite, and looked as if it were dumped there at random. But, like the other exhibits in the museum, it had a sign above it explaining what it was.

OMPHALOS,

it said, and then, in Greek letters, what was presumably the same thing: OMFA?OS.

“What the devil’s an omphalos?” he asked Edelsheim. A couple of Russians scrambled out to drag off a wounded man. He didn’t fire. A minute’s worth of truce wouldn’t matter.

“Beats me,” the sergeant answered. “Animal, vegetable, or mineral?”

“Mineral.” Hasso jerked a thumb over his shoulder.

Edelsheim looked, then shrugged. “I’d say that honking big rock is. What the hell is it?”

“It’s Greek to me,” Hasso said. But he was curious enough to crawl over to read the smaller print under the heading. When the world was falling to pieces around you, why not indulge yourself in small ways if you could? He wouldn’t get the chance for anything bigger - that seemed much too clear.

“Well?” the

Feldwebel

asked.

‘“The Omphalos Stone, from Zeus’ temple at Delphi, was reputed to be the navel of the world,’” Hasso read. ‘“It was the center and the beginning, according to the ancient Greeks, and also a joining place between this world and others. Brought to Berlin in 1893 by

Herr Doktor Professor

Maximilian Eugen von Heydekampf, it has rested here ever since. Professor von Heydekampf’s unfortunate disappearance during an imperial reception here two years later has never been completely explained.’”

“Ha!” Edelsheim said. “What do you want to bet some pretty girl disappeared about the same time?”

“Wouldn’t be surprised.” But Hasso’s eyes went back to the card. “‘And also a joining place between this world and others.’ I’ll tell you, Karl, this world doesn’t look so good right now.”

“So plunk your ass down on the rock and see what happens,” the sergeant advised. “How could you be worse off, no matter where you end up?”

The shooting picked up again. Someone not far away started screaming on a high, shrill note, like a saw biting into a nail. The shriek went on and on. That was no sham. That was a desperately hurt man, one who would die soon - but not soon enough to suit him.

“Good question,” Hasso said. “Another world or this same old fucked - up place? Here goes nothing.”

The patched seat of his field - gray pants came down on the navelstone. Sergeant Edelsheim turned his head to jeer at the captain while he was on the rock. The whole goddamn country was on the rocks now. That was pretty funny, when you “What the - ?”

One instant, Captain Pemsel was there. The next, he was gone, as if by trick photography in the movies. He might never have been in the museum with Edelsheim.

“Der Herr Gott im Himmel”

Sudden mad hope surged through the sergeant. If there was a way out, any way out... What he’d told Pemsel was true for himself, too. Wherever he went, how could he be worse off?

He turned and, half upright, scrambled toward the Omphalos. Half upright turned out to be a little too high. A burst from a Soviet submachine gun slammed home between his shoulder blades. He went down with a groan, blood filling his mouth.

One hand reached for the navelstone: reached, scrabbled, and, just short of its goal, fell quiet forever. And none of the tough Russian troopers who overran the museum cared a kopek for an ugly lump of rock they could neither sell nor screw nor even have any fun breaking. When the Omphalos seemed to stir beneath him, Hasso Pemsel wondered for a heartbeat if he was losing his mind. He hadn’t really expected anything to happen. He hadn’t really believed anything

could

happen. But what he believed didn’t matter, not any more. He’d mounted the stone with hope in his heart. That was enough - far more than enough.

He hung suspended for a timeless moment. What did Hamlet say?

O God! I could be bounded in a

nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space, were it not that I have bad dreams.

That came to Hasso only later. At the time - if

time

was the word for this flash of existence apart from everything - he knew only that, whatever else it was, it was no dream.

And then he was back in the world again - back in

a

world, anyhow - and he was falling. He dropped straight down, maybe a meter, maybe two: surely no more than that, or he would have hurt himself when he landed. Or maybe not. He came down in a bog that put him in mind of the Pripet Marshes on the Russo - Polish border.

Training told. As soon as he knew he was hitting water and mud, his hands went up to keep his weapon dry. A Schmeisser was a splendid piece when it was clean, but it couldn’t take as much crud in the works as a Soviet PPSh or a British Sten.

He floundered toward the higher ground ahead. The setting sun - or was it rising? - flooded the unprepossessing landscape with blood - red light. And that was one more impossibility, because it had been the middle of the day in Berlin.

Hasso shrugged and squelched on. Maybe he’d got shot the moment he plopped his can down on the Omphalos. Maybe this was nothing but a mad hallucination before the lights went out for good. But he had to act as if it was real. He’d spent too many years fighting to quit now. He’d been wounded three times. He was damned if he’d throw in the sponge for no good reason.

“Maybe I’m damned anyway,” he muttered. He shrugged again. If he was, he couldn’t do anything about that, either.

He hauled himself up onto dry land. As he did, he realized it was artificial, not a natural feature of the swamp at all. It was a causeway, long and straight and not very wide, with a well - kept dirt road atop it. Somebody needed to go from Here to There in a hurry, and the swamp happened to lie athwart the shortest way.

Somebody

badly

needed to get from Here to There in a hurry. This causeway would have taken a devil of a lot of work to build.

He stooped to examine the road. The long shadows the sun cast (it was setting, definitely setting) showed no trace of tire tracks or tread marks from panzers or assault guns. They did show footprints and hoofprints, some shod, others not. And there were unmistakable lumps of horse dung. Hand tools, then, almost certainly. Which meant...

Hasso Pemsel shrugged one more time. He had no idea what the hell it meant. It meant he wasn’t in Kansas anymore. He’d seen

The Wizard of Oz

when it got to Germany, just before the war started. A flash of motion on the road, off to the east. Before Hasso consciously realized he needed to do it, he slid into cover, sprawling on the steeply sloping side of the causeway. All the time he’d spent fighting the Ivans had driven one lesson home, down at a level far below thought: unexpected motion spelled trouble, big trouble.

Ever so cautiously, Schmeisser at the ready, he raised his head for a better look. As he did, he wondered how many magazines for the machine pistol he had left. Four or five, he thought. And what would he do once he used them up? He grunted out a syllable’s worth of mirthless laughter. He’d damn well do

without,

that was what.

Somebody was running up the road toward him. No, not somebody. Several somebodies, one in the lead, the rest between fifty and a hundred meters behind. The leader ran with an athlete’s long, loping strides. The others pounded along, showing not much form but great determination. The dying sun flashed off sharpened metal in their hands. They were armed, then. The man in the lead didn’t seem to be. A few seconds later, as the leader drew closer, Hasso sucked in a short, sharp, startled breath. That was no man running for his life. It was a woman, running for hers! She was tall and blond and slim, and the rags she wore covered enough of her to keep her technically decent, but no more. If she hadn’t been very weary, weary unto death, she would have left her pursuers in the dust. Her build and her gait said she was used to running in a way they weren’t and never would. But her sides heaved; sweat plastered her fair hair to her face. Plainly, she was at the end of her tether. How many kilometers had she run already, knowing it would be the end if she faltered even once?

Hasso’s hackles rose when he got a good look at the men who thudded after her. They were short and squat and dark, with curly black hair and the shadows of stubble on their cheeks and chins. One of them carried a hatchet, one a pitchfork, and the third what Hasso at first took to be a sword but then realized was a stout kitchen carving knife.