After the Tall Timber

Read After the Tall Timber Online

Authors: RENATA ADLER

RENATA ADLER

AFTER THE TALL TIMBER

COLLECTED NONFICTION

PREFACE BY MICHAEL WOLFF

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

OTHER BOOKS BY RENATA ADLER PUBLISHED BY NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

Speedboat

Afterword by Guy Trebay

Pitch Dark

Afterword by Muriel Spark

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

Selection copyright © 2015 by NYREV, Inc.

Copyright © 1965, 1966, 1967, 1968, 1969, 1970, 1976, 1979, 1980, 1987, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2003, 2015 by Renata Adler

Preface copyright © 2015 by Michael Wolff

All rights reserved.

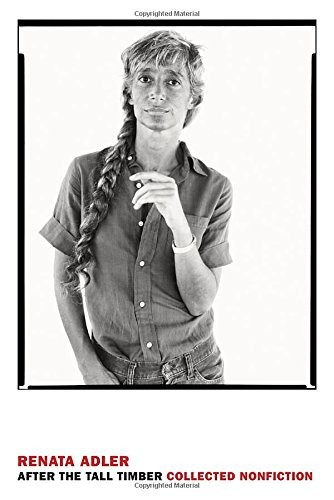

Cover photograph: Richard Avedon,

Renata Adler, writer, St. Martin,French West Indies, March 8, 1978

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

Jacket design: Katy Homans

Adler, Renata.

[Works. Selections]

After the Tall Timber: Collected nonfiction / by Renata Adler ; preface by Michael Wolff.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-59017-879-9 (hardback)

I. Title.

PS3551.D63A6 2015

818'.54—dc23

2014038528

ISBN 978-1-59017-880-5

v1.0

For a complete list of books in the NYRB Classics series, visit

www.nyrb.com

or write to: Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014.

FOR

STEPHEN

Copyright and More Information

Toward a Radical Middle

, Introduction

The March for Non-Violence from Selma

The Black Power March in Mississippi

Radicalism in Debacle: The Palmer House

But Ohio. Well, I Guess That’s One State Where They Elect to Lock and Load: The National Guard

A Year in the Dark

, Introduction

On Violence: Film Always Argues Yes

Three Cuban Cultural Reports with Films Somewhere in Them

The Justices and the Journalists

Canaries in the Mineshaft

, Introduction

Searching for the Real Nixon Scandal

The Porch Overlooks No Such Thing

RENATA ADLER has become something of a cult figure for a new generation of literary-minded young women since the 2013 re-release of her novels,

Speedboat

(1976) and

Pitch Dark

(1983). Those books represent an early point, and in many ways a high point, in the portrayal of a modern sort of angst—vulnerable women adrift in both the psychological and actual world. Adler herself can often seem like an iconic figure of fragility and lostness with her long bouts of literary absence and silence.

Here, however, in this collection of her most significant journalism, she is a diametrically opposite figure: a fierce and aggressive writer, known and feared and sometimes shunned for turning her stone-cold and contrarian judgments on her own professional class. I do not think it is an exaggeration to say that her writing is some of the most brutal ever directed at journalism itself.

Shortly before the publication of

Gone

, her broadside against

The New Yorker

and what the magazine became after it was sold in 1985 by its original owners, I was at a cocktail party on Manhattan’s West Side at the home of a

New York Times

cultural supremo attended by a set of publishing myrmidons of frightening standing and lockstep opinions. Following the whispered name “Renata,” I literally intruded on a clucking circle of these reproachful men planning their counterattacks against her: something must be done.

The writer Harold Brodkey, her friend and colleague at

The New Yorker

, once said to me, in the 1970s when she was having her famous and glamorous moment, that in his view, Renata could not decide whether to live an “interior writer’s life” or “an exterior activist’s life.” At the time, I thought his comment was about her work in Washington in 1974 with the House Judiciary Committee’s impeachment inquiry staff, where she had become a sort of history’s ghostwriter—recruited to make inarticulate politicians sound like men worthy of impeaching a president—and then her decision, at the peak of her fame, to enroll at Yale Law School. Should she seek real worldly power or continue as a mere writer on the sidelines? (It is quite extraordinary to consider that real power might have been within her grasp.)

In fact, I think I misunderstood what Brodkey was saying. What she was wrestling with was not career suitability, but her divided nature: on the one hand, muddled fear and vulnerability, and on the other, clearheaded outrage and scorn.

These feelings are not, of course, mutually exclusive.

A person’s vulnerability and fears do not mean that he or she cannot also summon a particular courage. Perhaps such fear compels a person to redouble his or her efforts and boldness. Adler, who, among her friends, is well known for not being able to navigate a few blocks or keep her possessions about her, nevertheless, during a particular period of twentieth-century turmoil showed up for the civil rights movement in Selma, Alabama, the genocidal conflict between Nigeria and Biafra, and the American descent into Vietnam.

It is this contradictory nature, I believe, that has made her such a conundrum: she seems so appealing and uncertain (ever in need of protection) and then changes her clothes and goes to war. Not to mention the fact that she has often gone to war with her own colleagues, making her not just a confusing figure but an anathema as well.

At some point, perhaps quite unaware, she crossed over from a career as a cosseted insider to a what-ever-are-we-going-to-do-with-her outsider.

She was born in Milan in 1938 to parents fleeing Nazi Germany. She grew up in Connecticut and went to Bryn Mawr, then to graduate school at Harvard and the Sorbonne. In 1963 she joined

The New Yorker

as a staff writer.

For the next twenty years or so, she was a leading light in a particular brilliant period of American writing. She was an “it” girl, complete with the iconic look and memorable pictures by Richard Avedon, provocative and fashionable. (I recall my parents, culture vultures in suburban New Jersey, discussing her with great awe.)

The New Yorker

then was the equivalent of something similar to HBO now—you wouldn’t have missed it, or her.

In 1968, she became the

New York Times

film critic (the first woman in the job when being the first women was a miraculous transformation) at a moment when writing about film was, arguably, more influential than making films—and when

The New York Times

was the first and last critical word. In the early 1970s, she went to Washington where she became the Watergate committee’s writer—at the epicenter of the most momentous public event of the era. Then came

Speedboat

, followed by Yale Law School, then

Pitch Dark

; then came her book

Reckless Disregard

, about the big twin libel lawsuits of the early 1980s, Westmoreland suing CBS, Sharon suing

Time;

and then, practically speaking, nothing.

Writer’s careers, even ones that have reached a great height, are fragile things, and they can go wrong for many reasons and as the result of many choices: money, drugs, Hollywood, among others.

But Adler’s career goes wrong, or at least astray, or far from the light, primarily for not being able to keep her silence. Adler is a good demonstration of the boundaries of art, that even serious writing is harshly proscribed, that the literary life has hard rules, that politics must be carefully played, that renegades—and, no doubt, especially women renegades—who go past an undrawn line are cast out.

She surely managed to cross many of the mightiest and most thin-skinned cultural institutions and arbiters. She offended

The New York Times

: first, writing excessively scathing film reviews for the paper; and then, a worse sin, quitting the

Times

after a year and returning to

The New Yorker

. Even now, with the

Times

having lost considerable power and clout, it is difficult to pursue a serious career in letters with its institutional disapproval shadowing you. And it has, literally for decades, pursued an odd, sour, spurned lover’s vendetta against Adler (compounded and renewed by Adler’s reflexive counterattacks on the paper), which she dissects in the introduction to

Canaries in the Mineshaft: Essays on Politics and Media

(2001), included here.

There is, of course, her famous—or infamous—review of Pauline Kael’s book

When the Lights Go Down

. It’s hard to remember what a cultural despot Kael, then the

New Yorker

’s film critic, was when Adler wrote her review in 1980. Kael was bully, drama queen, suck-up, disciplinarian, hysteric, and—taking jobs and inducements from the people she promoted—a bit corrupt, too. Still, opprobrium yet attaches to Adler for her sweeping emperor’s-new-clothes leveling of Kael; and it certainly earned her no points with

The New Yorker

, their mutual employer. But the rightness of Adler’s view of Kael as nasty, self-promoting gasbag only become more obvious as Kael’s reputation disappeared after she lost her

New Yorker

post and power. She was unreadable, said Adler; and indeed, Kael is unread now.

Adler’s cheerfully absurd recollections of the editing process at

The New York Times

, which serves as an introduction to the collection of movie reviews she wrote during her year, at the age of thirty, as the

Times’

s chief film critic, is perhaps the best exegesis of the leveling and zero-sum game that editors so often play, and another thwack on the

Times

’s nose.

Then, there is her Watergate view. She is one of the few—perhaps, the only—more-or-less liberal party to the proceedings to argue, against the orthodoxy of pretty much the entirety of liberal media, that, all in all, it was a fairly weak case against Richard Nixon (and that the real reasons for his resignation were hidden from view).

Oh yes, and you should hear her on Bob Woodward and Deep Throat. I don’t know anyone else who has pointed out that Mark Felt—identified upon his death, years later, by Woodward as Deep Throat—was widely briefing, dishing to, and confiding in almost everybody involved in the investigation. He became, in other words, the happenstance face for what every professional journalist of a certain age knows to be—though, given Woodward’s reach, few will say so—a convenient composite.

It is extremely difficult to explain how Bob Woodward’s career could have progressed after Adler, on more than one occasion, took him apart. But then again that is the point about Woodward and Adler’s critique of him, he—quite unlike Adler herself—has always existed in a compact with the power centers that he covers.

If there is anyone who has violated the clubbiness of the literary and journalistic world more than Adler I cannot think of whom.

Among the reasons, I believe, that she seems so fierce, impolite, unexpected, even outré, is that she has no politics—or no official politics. In her introduction, included here, to

Toward a Radical Middle: Fourteen Pieces of Reporting and Criticism

(1970), she offers perhaps one of the last defenses of centrism as a definition of reasonability and intellectual honesty. The irony of course is that it is centrism itself that has become a contrarian, radical and disturbing.

As she presciently described long ago, television talking heads (before they were called talking heads) are spokespeople whose positions can always be predicted; Adler’s cannot because they are not based on membership in a particular club or linked to a commercial persona (or, now, a brand), unlike the myriad pundits whose worth is based on the consistency of their views. What is to be made of the usefulness or intellectual integrity of journalists and commentators whose positions are always known? They might as well never write at all—saving time for everyone. And yet, of course, the market accommodates them, whereas unanticipated views are met with hostility and confusion.

Adler is trying to write about people’s motivations, about their inherent conflicts, about not what they say they believe in or stand for, but the largely happenstance circumstances that got them to their chance moment in the sun. All people and all events have another story. Nothing is as it represents itself to be. That is bound to be an unsettling and unpopular analysis.

Her politics, to the extent that she has any proscribed position, has to do with language. She unpacks to startling effect what people are actually saying. She is one of the few writers who hold people accountable for the words they use. In doing so, meaning, or assumed meaning, often falls quickly away, and laziness, buffoonery, ignorance, and worlds without the most basic logic are revealed.