Afterlands (12 page)

She had told her husband she considered it a mistake to kill and eat the last dog.

Ebierbing! she calls.

He sits up.

Suna?

Even in the dark she can tell he is not truly and capably awake. Those who are most fully, perfectly awake in the daytime are the most perfectly asleep at night. A needle cry from the crewmen’s iglu—the steward, she thinks—and this time it is a cry of pain as well as terror. She pulls out the ink drawer of Father Hall’s writing-desk and takes a bullet from her husband’s loonskin pouch and without donning her fur pants or amautik she crawls out through the entryway where he keeps his rifle and grabs it and stands up outside. The dense, pulsing stars and a bruise green ribbing of aurora borealis thinly light the floe: fifty paces away the emaciated he-bear hunches over the shattered iglu, digging down with his forepaw as if for a wounded seal through the ice. Disembodied arms stick out through the walls, frantically groping for the rifles picketed around it. It looks odd, funny, as if the men are trying to escape through the iglu walls—to pull themselves through into the open. Loading the rifle, Tukulito kneels. One of those reaching arms has just found and dragged a gun into the iglu. The steward is screaming louder. She takes aim. A second rifle is pulled inside. The bear dips his long head, probing deeper still. The head comes back up. Again she aims, then pulls the trigger. The snapping report has an instantaneous echo, as if resounding off a cliff face near by, and for a moment she believes that a high berg, or even the coast of Ellesmere Land, is upon them; then realizes that somebody in the iglu has fired as well. Hit twice from different angles the bear straightens abruptly, as if hearing with astonishment somebody calling his true and secret name, then flops heavily backward onto the ice, head to the side, tongue lolling.

Tukulito stands up in her lace-trim nightdress. Punnie has followed the lieutenant out of the iglu; the two on either side of her now. The child takes her trembling hand. From his own iglu Hans has just emerged, armed, his whole family swarming out after him, always hungry for distraction. Seeing her friend Succi, Punnie scutters off to join her.

The lieutenant seems to want to reach a bare hand to Tukulito’s shoulder, but holds back. I hadn’t realized you could handle a rifle, Hannah, he says in a soft, awed tone.

I have not for some years, sir. But I have seen my husband use one often enough.

Dec. 7

. It is over a month since we lost sight of all land. The sun we lost even earlier, yet our eyes have become partially adapted to this dim light; as it has come on gradually, it does not appear so dark to us as it would to one suddenly dropped down on our floe from the latitude of New York. They would find it perhaps as dark as some of the shut-up parlors into which visitors are turned, to stumble about until they can find a seat, while the servant goes to announce them.

I have been over the floe, to the “shore” where our

Polaris

last anchored, after some canvas we had stored there. I called on the men for help and four responded—the steward, the cook, Madsen, and Lundquist. (Kruger, I noted, was not in the hut; the steward believed he had “gone out for air” or perhaps was “off trying to hunt.”) This canvas I wanted to line the hut of the native, Hans. He has worked late and early to make the men comfortable, and they have their hut well lined, and the natives’ ought to be too, especially as the children are there; and Hans’s wife, like Hannah, is continually working for the men, by mending and making for them. Moreover Hans is sick, and can not hunt. Only Joe goes out sealing these days, although with no luck. Our day’s allowance is now divided out by

ounces

: five of biscuit, six of canned meat, one and one-half of ham. These ingredients are mixed with brackish water to season them, and warmed over the lamp or fire.

I do not write every day—

it would take too much paper

. I had some blank note-books and ink in one of the ship’s bags, but on looking for them a few days ago, found they were all gone. Some among these men will seize hold of any thing they can lay hands on; then, too, there are those who might prefer that I not keep daily note of what is happening out here, where I can scarcely get an order obeyed if I give one. The storehut—a smaller

igloo

—continues to receive secret visits. With the return of light and game, I hope things will be better; but I must say I never was so tired in my life.

Dec. 9

. Last night, being clear, Mr Meyer was enabled to take an observation. He seems slightly stronger now, as if the men’s fealty is food to him; which of course is not the only explanation possible. Several of his instruments, he says, including a compass and altazimuth, which he left outside “briefly unattended,” have been mislaid or taken—and here he gave

me

a suspicious look—but he has still his sextant and ice-horizon, and also a star-chart; and so he took the declination and right ascension of y, Cassiopeia. But he has no nautical almanac to correct his work by, so that he can only approximate our latitude. He makes it 74°4’ N. lat., 67°53’ W. long.; but I do not think it is any thing like that. If we are as far south as that, we have drifted faster than I consider possible.

We lie still in our snow burrows much of the time, partly because there is nothing to do—it is too dark to do any thing—and also because stirring round and exercising makes us hungry, and with the meat of our starved bear so soon finished, we can not afford to eat more. The stiller we keep and the warmer, the less we can live on; and, moreover, as I have said, my clothing is very thin and quite unfit for exposure in this cold.

Dec. 11

. Increasingly Mr Meyer and I are in dispute as to the direction of our drift. He believes we are going to the east, toward Greenland; but we are surely going to the west. He judges, I suppose, by the winds being mostly from the north-west; but the ice does not obey the winds—heavy ice, I mean, like this. Heavy ice obeys the

currents

, and if they have not changed their natural course, we

must

be going to S.S.W. It would not matter in the least what opinion was entertained as to the course of the floe, only that it makes the men too hopeful, thinking they are approaching Greenland, and nearing the latitude of Disko, where they know there is a large store of provisions left for us. I am afraid they will start off and try to reach the land on that side; if they do, it will mean

death

to all of them. After living on such short allowance for so long, none could hope to bear up under the fatigue of walking and dragging their supplies over this rough hummocky ice. Moreover they would surely take the boat, perhaps loaded with all our provisions, thereby leaving us and Hans’s family completely without resource, and likely ensuring our deaths as well.

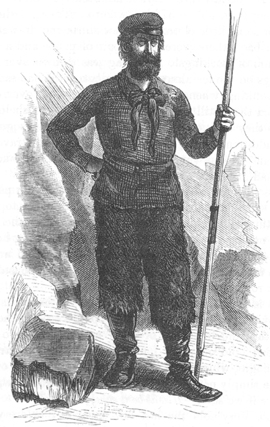

CAPTAIN TYSON IN HIS ARCTIC COSTUME.

I see the necessity of being very careful, but I shall protect the natives at all cost, for they are our best, and I may say only, hunters—though the

crewmen

seem to think them a burden, particularly Hans and his family, and would gladly rid themselves of them. Then, they think, there would be fewer to consume the supplies, and if they moved toward the shore, there would not be the children to lug … I believe Mr Meyer has told them of the drift of the

Hansa

crew, and the gratuity of one thousand thalers donated by their Government to each man of that party, so they think if they should drift likewise they would get double pay from Congress. Little do they see the difference in circumstances! The

Hansa

crew had ample time to get all they wanted from the vessel—provisions, clothing, fuel, and a house-frame. And their drift was through less severe climes. However, these crewmen are organized now—swaggering about with their weapons, speaking loudly in German—and appear determined to control.

The fear of death has long ago been starved and frozen out of me

; but if I perish, I hope that some of this company will be saved to tell the truth of the doings on board the

Polaris

, and especially here on the ice. Those who have baffled and harmed this expedition ought not to escape. They can not escape their God!

Boredom and rage sound like opposite states of mind. In Tyson they’re now states of body and they share the same cramped interior space. Restless and active by nature, he’s now confined in the hut to a space a few feet square; a whaling captain and then on the

Polaris

lieutenant-captain, he can no longer exercise the deeply physical thrill of command; virile and accustomed to conjugal privilege, he’s forced to lie in celibacy pressed against a near-naked, astoundingly warm-skinned woman.

He wakes from dreams where his voice can’t project, legs can’t move, hands won’t grip. Now that he’s awake certain thoughts creak into cyclic action and gather momentum, like a prisoner on a treadwheel. A drink might stop or slow them—God, if only! There has never been a successful mutiny among the crew of an American ship. He signed on for glory and now faces ruin (and death, though that’s a minor concern). If the crewmen flee and die on the ice, his disgrace. If they

succeed

despite his warnings and he and the natives should die … disgrace! There has never been a full mutiny among a USS crew, and now his name will go down in the schoolbooks as the first ranking officer to suffer one. His little son having to read, memorize,

recite

those words in the schoolroom, standing hot-faced at his desk while the children leer and the schoolma’am turns a blind eye to this cruelty—the boy’s rightful legacy, after all. George Jr. thus loathing his father’s memory. Emmaline, widowed, passing through a daily gauntlet of eyes, grateful for her black veil … or a black poke-bonnet laced tight around her shame. Widowed, yes, because he cannot imagine surviving such disgrace. For there has never been a full and successful mutiny among the crew of a U.S. …

A bitter draft breaks into this spiral, Tukulito shifting under the skins with a cough. Tyson’s face is left uncovered. He opens his eyes: moonlight diffused through the pane of ice. She is on her hands and knees an arm’s length away, Ebierbing kneeling behind her, rolling the lace hem of her nightdress up over her haunches. The exposed skin gleams like smoothed marble, strangely white in the lunar glow. Ebierbing’s dark Mongol face is clenched. Her white buttocks block his shadowed groin from view. Like a Chinaman with a white woman, thinks Tyson. The couple is silent. Their breaths visible but silent. Tyson has wondered if they ever did this, yes, though he never wondered if they did it

in this way

, because it has never occurred to him that one might. Like dogs, or cattle; and in front of the child, who might wake at any time! Yet his physical response suggests less than complete disapproval. But then, shame and disgrace—both of which he feels as a witness to this moment—are for Tyson not sexual deterrents, but an inevitable part of sex, perhaps even stimuli. Poor Adam’s birthright. Ebierbing grips her flanks, bucking his goat-hips faster, his lean torso, steaming in the cold, lapsing slowly toward her back. Tyson is relieved that both faces are in shadow. Especially hers. But as Ebierbing bends closer she pushes up on her arms, arching back to meet him, turning her face toward his so that the moonlight catches it. Her eyes are shut hard. She’s biting her lower lip. Tyson means to shut his own eyes completely, but can’t. Can’t help holding himself hard, his shame, as he, Ebierbing, reaches under to grip her hanging breasts through the nightdress. He gnaws on her nape. Her braids dangle and swing. She puffs a short breath through her nose. She smiles, by God, Hannah smiles, she with her fine manners and proper accent, who had seemingly acquired all the feminine virtues, who had seemed so

white

. But the blanching moon is transforming her into a very different creature; or, perhaps, exposing a truer self. Ebierbing shudders and tightens and Tukulito cranes her head farther back to clamp her small teeth onto his throat and he lets out a creaturely moan, quickly stifled. And then her eyes part slightly. The wet, glinting pupils seem to fix on Tyson’s squinted eyes. And he is certain that she knows, somehow, that he’s present.