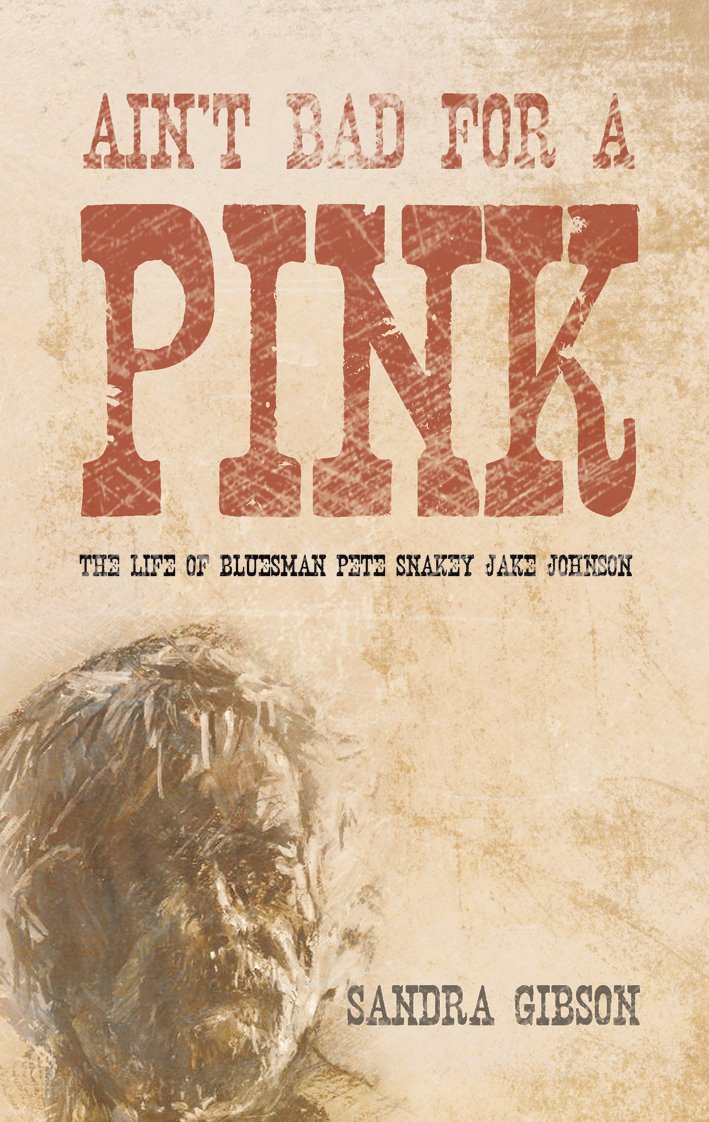

Ain't Bad for a Pink

Read Ain't Bad for a Pink Online

Authors: Sandra Gibson

Pete “Snakey Jake” Johnson

Pete Johnson is a musician with a long career in blues music, specialising in the country blues of the Twenties and Thirties. He is also an acknowledged connoisseur of vintage guitars and an innovator in the field of sound systems.

Sandra Gibson

Sandra Gibson is a writer with a special interest in art and music. She has written promotional material for art exhibitions and reviews for

Art Of England, The Nerve

and

Circa

magazines. She also writes poetry and fiction and is currently completing a novel.

The life of bluesman Pete 'Snakey Jake' Johnson

Grey-dawn motorways and yachts on silver seas; whisky with Peter Green and slide guitar with Son House; coffins riding the flood waters of Albany and moonlight on the railway line: the life of bluesman Pete “Snakey Jake” Johnson.

Sandra Gibson

Written from conversations with Pete Johnson and friends.

Copyright © 2011 Sandra Gibson

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Matador

5 Weir Road

Kibworth Beauchamp

Leicester LE8 0LQ, UK

Tel: (+44) 116 279 2299

Fax: (+44) 116 279 2277

Email:

[email protected]

Web:

www.troubador.co.uk/matador

ISBN 978 1780889 689

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset in 12pt Palatino by Troubador Publishing Ltd, Leicester, UK

Matador

is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd

This book is dedicated to Dobro

Dobro is the name given to the type of resonator guitar I so admire. It’s a contraction of Dopyera Brothers coined when their company was set up in 1928. I named my dog Dobro and one day recently he was a bit lively and I kept having to call him to me. I soon noticed that people passing by were smiling and acknowledging me. I later discovered that “Dzien dobry” is a Polish greeting and “Dobry den” is a Czech greeting – hence my popularity with the local immigrants!

So the dedication has three aspects.

On Thursday 12

th

March 1998, at Whippoorwill Studios, Smyrna, Georgia, I recorded a CD of country blues songs: the pinnacle in a long career as a musician and a tribute to the bluesmen I admire. It was all finished in four hours on my mother’s birthday and this convergence of important event and significant date created the pivotal moment at which I started to assess my life.

This book is about a lad from Crewe who loved the blues. And it’s about those about me and the times we had and it’s about the music. That’s it, really.

From Bridget’s Barn To The Brunswick:

A Tug Of Love

My early years were mauled by powerfully emotional experiences propelling me towards the inevitable. I was like a rugby player running with the ball, temporarily slowed down by counter forces but certain of reaching the touchline.

I was born in Crewe in 1949, within the echoes of World War II and within the sounds of the steam trains giving the town its heavy metallic life. There was a moment in my infancy that caught the social and economic change I would inherit: my earliest memory, aged two, is of a vast, unrecognizable object that blinded me with its whiteness. My mother, my father and their three sons were gazing in awe at that powerful symbol of affluence and renewal, only understandable, only remarkable, in the context of the Fifties.

A bath. A bath in its own room.

I had been born into an era of state welfare and educational and economic opportunity which was to transform the lives of ordinary people. My hands, now sticky with Farley’s Rusks, would soon dance across a guitar and within two decades steer my first yacht.

Personal memories of my grandparents are vivid though few. Grandma Sophia Johnson had been abandoned by her husband in the 1920s – this was never spoken about – and was supported at all levels by the Christadelphian Church. I remember her in two modes: as part of the nineteenth century – old and frail, her mass of grey hair down her back and coiling out of the bed, reading, according to Christadelphian tradition, seventeen chapters – why

seventeen

? – from the Bible every day, or part of the twentieth century – screaming about with me in my Turner Climax to visit her sister in Timbrell Avenue for tea and cakes.

I still have Sophia’s recipe for pickled eggs.

If Sophia was from Dickens, granddad Rafe Billington was from

The Wind in the Willows.

What they shared was a love of speed. He was a Class 1 train driver who broke more than a time record for travelling from Carlisle to Crewe: all the crockery on the train smashed, so fiercely were the brakes applied on arrival. Ralph’s vehicular prowess extended to the road. He had an open Austin Seven: a yellow model he drove like a train. His handlebar moustache flapping in the breeze, he’d be honking the horn, expecting everyone to get out of the way. Two of his fingers were missing – lost when some machinery backfired at the site of a rail crash. He used the stump of one of them to pack his pipe down, even when it was lit! I inherited my grandfather’s liking for fast cars but also something far more serious. He had Dupuytren’s Contracture, a syndrome inherited from the Vikings from which I also suffer. It causes the tendons in the hand to contract so that it looks arthritic and clawlike, I remember my grandfather’s hands looking this way. Dupuytren’s Contracture has severe implications for a musician as we shall see.

Ralph’s wife Minnie – my maternal grandmother – is associated in my mind with a cosy kitchen in Ruskin Road, Crewe, redolent of hot pot. Being profoundly deaf didn’t stop her lipreading six conversations simultaneously.

I’ve often wondered why my grandfather John Johnson left his family: was he traumatised by the Great War or by the aftermath? What made him unable to cope with family life? I don’t know what became of him but poverty filled the gap he left. Nevertheless, partly because of the kindness of the Church, his family lived a respectable and religious life.

Looking at the evidence, I don’t think that cowardice was much of a

motif

in the Johnson family. My father Norman Johnson was conscripted in 1940 and went to fight in Africa, Italy and Europe. His brother Mont had a different kind of courage: he was a conscientious objector and went to prison for his beliefs. My father always felt disappointed that he had lacked what he regarded as Mont’s superior courage yet after his death I discovered he was probably the most decorated and longest serving private in the Second World War, resisting promotion at all costs so that his decisions could not affect many lives. He always shrugged off his role

(1)

in the war, saying, “I was just a surveyor.” But what did this mean? It meant he did a dangerously exposed front line job gauging enemy fire. He was unimpressed by the trinkets of glory; my mother picked up his medals and he gave them to his first son Ralph to swap for cigarette cards. Being a painter and decorator in civilian life with an interest in buildings and art, he valued far more a set of unsent architectural postcards from every place he passed through. The only other statement he made about his army service was: “The army taught me to smoke.” He described a room with a false floor: the officers were above the floor, the men beneath. They were planning manoeuvres. The men were instructed to blow smoke through allocated gaps in the floor to represent gun emplacements – a ludicrous activity worthy of Spike Milligan.

I would describe my father as an intelligent man whose lack of education wasn’t his fault. It was to be the next generation that would benefit from universal education regardless of class or wealth. I feel I inherited strength, determination and courage from my father but I didn’t absorb his religious beliefs and to be fair I wasn’t pressurised to do so. Ideological clashes between us did occur but this was later when I reached adolescence determined to be a rock musician. In view of his impoverished early life, it was understandable that my father would want economic stability and respectability for his three sons. We forget how shocking my ambition was – being in a rock ‘n’ roll band was like being an outlaw. Parents in the post-war era became increasingly alarmed at the emergence of a youth culture with its own views on music, politics and – worst of all – sex.

My mother, Albina Betsy Boswell Billington, came from a more economically sound background than my father and was privately educated. She was a resourceful, energetic woman who bought her own house – the basis of her hairdressing business – whilst her husband was in the army. A wartime photograph shows her looking like Vera Lynn, upwardly mobile in a fur coat without fear of censure or failure. She was certainly no ordinary housewife; both she and my father had been racing cyclists of some repute. Their common interest had neutralised the social differences between them and people said they were made for each other. This was a modern relationship: they never argued; they

discussed

things. I inherited my mother’s business acumen and resilience – I ran my own business and owned a house at an early age as she did – and I was also influenced by her feminism in my choice of women.

But my mother dominated my life in a more profound sense. When I was three and a half my childhood ended. I watched an ambulance drive away – my mother had collapsed in the street – and although my infant’s mind was probably as interested in the vehicle as it was distressed by the event, that was the beginning of twelve years of anguished uncertainty and the feeling of death hovering over everything. From the point when the ambulance disappeared with my mother – and my childhood – I had to learn to be self-reliant.