Airmail (21 page)

Authors: Robert Bly

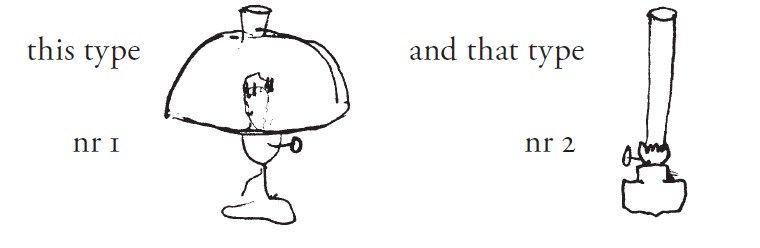

I have the former in mind, when reading the poem, but I have the suspicion that you have the latter. “The chimney” must be the glass pipe of nr 2. I imagine the islands/moths crawling over the s h a d e of nr 1. Could it be called “chimney” too? Love Tomas

20 Nov, ’70

Dear Tomas,

Here are “PRELUDES.” It’s hard to decide on the pronouns for the first two stanzas of part II. And this is just a first draft typed up to see how it looks.

I’m not sure if you’d like the suggestion on the wall paintings to be:

The outline left behind on a wall when a picture that has been there a long time is removed

or

Perhaps the pictures are

still

hanging there on the wall.

Help me with this!

BOSWELL

I

I shy from something that comes hurrying katty-corner through the blizzard.

Fragment of what is to come.

A wall gotten loose. Something eyeless. Hard.

A face made of teeth!

A wall, alone. Or is a house there,

even though I can’t see it?

The future...an army of empty houses

feeling their way forward in the falling snow.

II

Two truths approach each other. One comes from inside, the other from outside,

and where they meet we have a chance to catch sight of ourselves.

The man who sees what is about to take place cries out wildly: “Stop it!

the hell with it all, if only I don’t have to know myself.”

And a boat exists that wants to tie up on shore—it’s trying right here—

in fact it will try thousands of times yet.

Out of the darkness of the woods a long boathook appears, snakes in through the open window,

in among the guests who are getting warm dancing.

III

The apartment where I lived over half my life has to be cleaned out. It’s already empty of everything. The anchor has let go—despite the continuing weight of grief it is the lightest apartment in the whole city. Truth doesn’t need any furniture. I have made a big circle around my life and come back to its starting point: a room blown empty. Things I loved so much now appear on the walls like Egyptian paintings, scenes from the inside of the grave chamber. But they are more and more blown clean. For example the light is too stark. The telescope held up to the sky. It is silent as a Quaker’s breathing. All you can hear are the doves in the back yard, their cooing.

24 Nov, ’70

Dear Tomas,

May Swenson is a poetess of very dubious ability whom I know fairly well. Her parents were Swedish, from the country, converted to Mormonism by Mormon missionaries, and so transported to Utah!!! where May Swenson grew up. She’s lived in N.Y. for years now. She is very anti-man. I remember an incident from the gathering of poets at Houston several years ago. Don Hall was there, round and full of childish, stomach-type charm and warmth as always. Two young girls—about 15—who called themselves the Houston Society of Young Poets, had taken a liking to Don’s face, and had presented him with a balloon. It was a sort of formal reception, in a ballroom, and Don looked lovely, walking around with his blown up balloon floating about him. He suddenly came to me, mad as a wet hen. I said, What’s the matter? He said, “May Swenson pricked my balloon!” (She had just put her lighted cigarette against it, looking him in the eyes, and popped it.) He said, “That’s the meanest thing I’ve ever seen a human being do!” He was crushed.

She belongs at the same time to an elegant, conservative, rather decadent we-like-rich-folks literary set in New York—they’re always on prize committees of the American Academy of Arts & Letters and such things—and so I’m sure she

does

like your poems, and also thinks it would be a

favor to you

to rescue you from the barbarian, Robert Bly—

So let her go ahead—you really can’t stop her anyway. And maybe you can improve her translations a bit. It will be interesting to see what she does.

For “The Name”—try this:

But it is impossible to forget the fifteen second battle in the hell of nothingness, a few feet from a major highway, where the cars slip past with their lights dimmed.

Sometimes patients in hospitals will describe the “sense of nothingness” they felt while under ether.

Both “oblivion” and “forgetfulness” are impossible, and never used in spoken English any more. Do you think “the hell of nothingness” would be a possible solution?

I enclose “At the Riverside.” I’m not sure I understand the visual suggestions of “snurrar trögt och hjälplöst hän.” I hope you’re happy having mocked me about the mercury thermometer. Capricorns are very sensitive to mockery—spiritual hemophiliacs...

Yours as always,

Robert

P.S. Would you send me another copy of

Mörkerseende

? I want to use it as a model for the pamphlet, and my copy is wroten on (to speak in Anglo-Saxon). Thanks.

25 Nov, ’70

Dear Tomas,

I’ve now finished the first draft of

Mörkerseende

! Here are the last two, “Traffic” and “The Bookcase.”

I need some help on Bookcase. Check the tenses carefully throughout. The last sentence of the second stanza is still very difficult for me, even though I know roughly what it

means.

The problem is that there are so many shades of meaning, which I can turn the reader towards by slight alterations in the English, and I don’t know what to do. Would you write me a few sentences, discussing each part of that three part sentence (beginning “Man kan tydligen inte resa”), and its relation to the rest of the poem.

I’m sending the third draft of Traffic. I had a lot of trouble with that poem; I think it looks fairly good now. “Mr. Clean” is a man in a white suit who appears in television commercials, I think for household cleaning products, useful as I recall for kitchen sinks, toilets, etc. He is a cartoon character.

In this draft I tried “chassis” (I haven’t checked the spelling of the plural)—a word used mainly for car bodies, but taken over from the French word for, I expect, carriages. The old Chevrolets always had a small metal plate by the running board saying “Chassis by General Motors,” meaning someone else may have made the motor and tires. “Vehicle” is no good, implying wagons.

For the horsechestnut tree shall I use “melancholy” or “sinister”? The first is passive, the second active.

For “periscopet,” do you want us to see a periscope on a submarine, or some general kind of telescope?

I’m going off next week now to Indiana and Ohio, to get the money for the next month, and when I get back, I’ll try to absorb your various comments, and type a complete draft, which I’ll send to you to read when you have insomnia.

I haven’t seen

Böckernas Värld.

Maybe it was sent by boat.

On Minnesota elections: Zwach is the man from our county and the neighboring county. He is a total dope. Odin Langen is from the far north, and represents pulp-cutters, Indian-haters, and poachers. Fraser is a pretty good man, representing the university community in Minneapolis plus a lot of suburbs, the kind in which there is always a poster of Che Guevara in the teenager’s bedroom, pinned over Early American Wallpaper.

Today is Thanksgiving. Nixon had hoped to have the prisoners of war rescued from North Vietnam at a Thanksgiving dinner

in the White House today.

Wouldn’t that have been marvelously sentimental? An orgy.

What an operation! Right out of Batman comics! No one can overestimate the effect of comic books on weak minds.

Love to all,

Robert

It was moved out of the apartment after her death. It stood empty several days, before I put the books in, all the clothbound ones, the heavy ones. Somehow during it all I had also let some grave earth slip in. Something came from underneath, rose gradually and implacably like an enormous mercury-column. You must not turn your head away.

The dark volumes, faces that are closed. They resembled the faces of those Algerians I saw at the zone border in Friedrichstrasse waiting for the East German People’s Police to stamp their identity card. My own identity card lay for a long time in the glass cubicles. And the dusky air I saw that day in Berlin I see again inside the bookcase. There is some ancient self-doubt in there, that reminds us of Passchendaele and the Versailles Peace Treaty, maybe even older than that. Those black massive tomes—I come back to them—they are in their way a kind of identity card too, and the reason they are so thick is because people have had to collect so many official stamps on them—over centuries. It’s clear that a man can’t really travel with heavy enough baggage, now that it’s starting to go, now that you finally...

All the old historians are there, they get their chance to stand up and see into our family life. You can’t hear a thing, but the lips are moving all the time behind the pane (“Passchendaele”...). I think for some reason of that ancient office building (this is a pure ghost story), a building where portraits of long dead gentlemen hung on the wall behind glass, and one morning the office workers found some mist on the inside of the glass. The dead had begun to breathe during the night.

The bookcase is even stronger. Looks straight from one zone to the next. A faint sky, the glimmery skin on a dark river that space has to see its own face in. And turning the head is not allowed.

The semi-trailer crawls through the fog.

It is the lengthened shadow of a dragonfly larva

crawling over the murky lakebottom.

Headlights cross among dripping branches.

You can’t see the other driver’s face.

Light overflows through the pines.

We have come, shadows chassis from all directions

in failing light, we go in tandem after each other,

past each other, sweep on in a modest roar

into the fields where industries are sitting on their eggs,

and every year the factory buildings go down another

eighth of an inch—the earth is gulping them slowly.

Strange paws leave a print

on the glossiest artifacts dreamed up here.

Pollen is determined to live in asphalt.

The horsechestnut trees loom up first, melancholy

as if they intended to produce clusters of iron gloves

rather than white flowers, and past them

the reception room—an out of order sign

blinks off and on. Some magic door is around here! Open!

and look downward, through the reversed periscope,

down to the great mouths, the huge buried pipes

where algae is growing like the beards on dead men

and Mr. Clean swims on in his overcoat of slime

his strokes weaker and weaker, he will be choked soon.

And no one knows how it will happen, we only know

the chain breaks and grows back together all the time.

Västerås 27 nov 70

Dear Master,

you have now translated 8 of 11 poems. You can see the light at the end of the tunnel.

“Preludes”: I think nr 1 and 2 have found very good English solutions.

The prose part, nr 3, has some mistakes in it. “Saker jag varit med om här” means “events from my earlier life that have happened here”:—this is too long and clumsy but it is the meaning of it.

Monica and I once visited the inside of a pharaonic tomb (the Sakkara pyramid) and in the very chamber where the dead king was previously put there were paintings on the walls, showing episodes from his life.

In this text I see the paintings from my life getting more and more vague until they disappear completely. As if you were showing a film and you gradually draw up the black blinds (curtains), letting in the light from outside—when the curtains are completely away you can’t see the projected film pictures anymore—the light is too strong. The text should be something like “but they are more and more effaced, since the light is getting too strong. The windows have grown bigger (larger?)”

“Kväkarandakt” has nothing to do with “breath.” “Andakt” means “devotion.” As you know the Quakers are silent during their divine service.

Affectionately

(I don’t sign—you know perfectly well who is writing)

(I am sitting in a train, shaking.)

More about Swedish pronouns in the

next message...

Västerås 29 nov -70

Dear Robert,

the gossip about May Swenson was invaluable. Do you think I have to visit this conservative, rather decadent, we-like-rich-folks set? Perhaps I can meet some of the Buckleys there and change history. The other day I fell asleep before my TV during a long film made by Peter Orlovsky. It was a film about Peter Orlovsky’s brother, who was just released from a mental hospital. The brother was autistic, sitting so quiet behind Ginsberg on a stage where a poetry reading was performed. I felt much sympathy for the brother. I did not see how the poetry reading ended—I fell asleep. In the night I had a dream about my future readings in the U.S.A., I was surrounded by shouting barbarians all the time. I looked in vain for some

holy

barbarian (you).