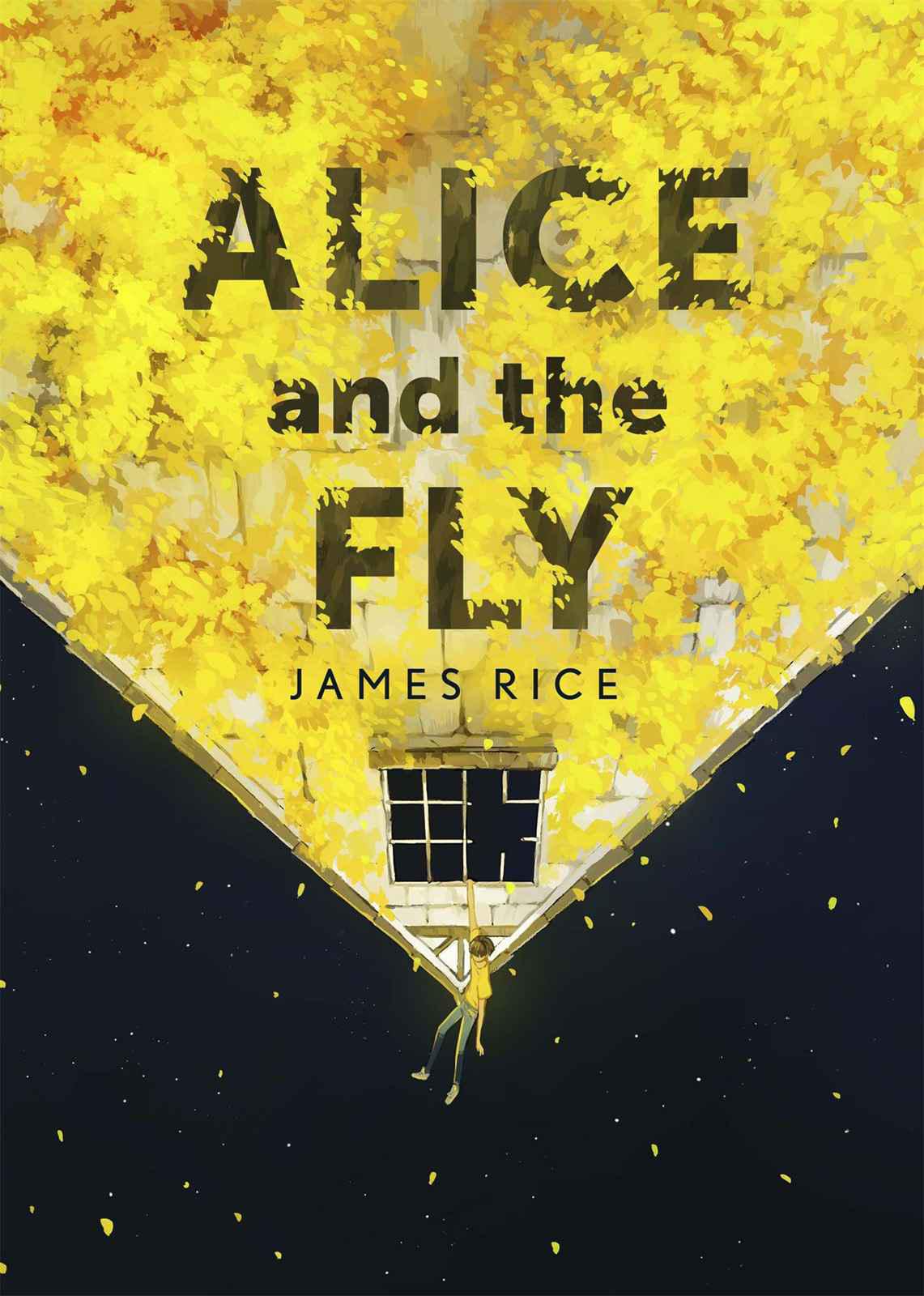

Alice and the Fly

Authors: James Rice

Contents

Alice and the Fly

is James Rice’s first novel. He also writes short stories, several of which have been published, and writes songs with his friend Josh. When he is not writing, he works as a bookseller in Southport.

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by

Hodder & Stoughton

An Hachette UK company

Copyright © James Rice 2015

The right of James Rice to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 444 79011 5

Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

For my parents, who are not the parents in this book – you are amazing and you raised me well.

Also for Nat, who is my favourite human being.

13/11

The bus was late tonight. It was raining, that icy winter rain, the kind that stings. Even under the shelter on Green Avenue I got soaked because the wind kept lifting the rain onto me. By the time the bus arrived I was dripping, so numb I couldn’t feel myself climbing on board.

It was the older driver again, the one with the moustache. He gave me that smile of his. A hint of a frown. An I-know-all-about-you nod. I dropped the fare into the bowl and he told me I’d be better off buying a weekly pass, cheaper that way. I just tore off my ticket, kept my head down.

The bus was full of the usual uniforms. Yellow visibility jackets, Waitrose name badges. A cleaner slept with her Marigolds on. No one who works in Skipdale actually lives here, they all get the bus back to the Pitt. I hurried up the aisle to my usual seat, a couple of rows from the back. For a few minutes we waited, listening to the click-clack of the indicator. I watched the wet blur of rain on the window – the reflection of the lights, flashing in the puddles on the pavement. Then the engine trembled back to life and the bus pulled off through Skipdale.

I got a little shivery today, between those first couple of stops. Thinking now about all those passengers on the bus, it makes me wonder how I do it every night. It’s not people so much that bother me. It’s

Them

. I heard once that a person is never more than three metres away from one of

Them

at any time, and since then I can’t help feeling that the more people there are around, the more there’s a chance that one of

Them

’ll be around too. I know that’s stupid.

We soon reached the Prancing Horse. Even through the rain I could make out the small crowd huddled under the shelter. The doors hissed open and Man With Ear Hair stumbled through, shaking his umbrella, handing over his change. He took the disabled seat at the front and made full use of its legroom. Woman Who Sneezes was next, squeezing beside a Waitrose employee, her bulk spilling over into the aisle. A couple of old ladies showed their passes, riding back from their day out in the crime-free capital of England. ‘It’s such a nice town,’ they told the driver. ‘It’s such a nice pub, it was such nice fish.’ Their sagging faces were so expressionless I could have reached out and given them a wobble.

And then there was you, all red curls and smiles, stepping up to buy your ticket, and the warmth rose through me like helium to my brain.

You were wet today. Shivering. You smelt of disinfectant, stronger than any other work-smell on the bus. Is it legal for you to work there? The landlord probably doesn’t realise how young you are. You look older. You’re not the prettiest girl in school, conventionally speaking. There’s a gap in your teeth and your hair’s kind of a mess with your roots coming through, and you always wear those thick black sunglasses, which is kind of weird. You have an amazing smile, though. Once I walked right past you and you smiled, right at me, as if we knew each other. It was only a slight smile, your cheeks bunching at the corners just the right amount, but it made me want to reach out and stroke them, brush them with the backs of my knuckles, like Nan used to with mine. I know that’s sad but it’s true.

You took your seat, on the front row. Working after school must tire you out because you always drift off as soon as you sit, sunglasses clinking the window with each back-and-forth roll of your head. We pulled off through the square, past Hampton’s Butcher’s. I couldn’t help thinking of your dad and the others, shivering with all that slippery meat while I was on the bus with you.

Then we turned onto the dual carriageway and sped out to the Pitt.

I wonder what it’s like, living in the Pitt. Do you tell anyone? I can’t think of a single kid who’d admit to living in the Pitt. It’s odd you have Skipdale friends, very few Pitt kids get into Skipdale High and even then they tend to stick to their own. Their families are always trying to set up in Skipdale but it does its best to keep them out. We have a Pitt neighbour: Artie Sampson. I’ve lost count of the number of times Mum’s peered out of the dining-room window and complained about him. She tells Sarah and me to keep away. ‘He’s trying to climb too high in the property market. He’ll fall and he’ll break his neck.’

There’s a physical descent into the Pitt, ear-popping and stomach-churning at the speeds the bus reaches, which might be why you choose to sleep through it. My father calls it the ‘Social De-cline’. I remember when I was little I’d play a game along the Social De-cline where I’d try and count how many houses were boarded up, how many were burnt out. Sometimes I’d find a house that was boarded up and burnt out. It was hard because Mum always drove the Social De-cline so fast, even faster than the bus does. It was as if the very air could rust the BMW.

Of course, you slept right through. Every pothole, every bend, every sudden break at traffic lights that threw us from our seats. The bus jerked and rattled so much it felt as if it might come apart, but you just slumped there, face pressed to the window. We stopped by the retail park and Old Man BO got on and sat right beside you but even then you didn’t wake up, didn’t even squirm from the stink of him. You stayed slumped, lolling like a rag doll, completely at the mercy of the rhythm of the bus. I watched you in the mirror for as long as I could, only looking away when the driver caught my eye.

We turned at the lights, past Ahmed’s Boutique. As always you woke the moment we passed the church, Nan’s church, just in time to miss the large black letters spanned over its sign:

LIFE: THE TIME GOD GIVES YOU

TO DECIDE HOW TO SPEND ETERNITY

You rang the bell. The bus pulled up at the council houses behind the Rat and Dog. You stood and thanked the driver, hurried down the steps with your coat over your head. I wiped the mist from the window and watched you blur into the rain. I felt that pull in my stomach, like someone clutching my guts. I wished you had an umbrella.

The trip back was even harder. I got shivery again, goose-pimpled. There were a lot of gangs out tonight, mounting bikes on street corners, cigarettes curling smoke from under their hoods. I nearly fell out of my seat when one of them threw a bottle up at the window. I wasn’t too bothered about people any more, though – all I could think about was

Them

. I lifted my feet up onto the seat. I knew they were everywhere I wasn’t looking. I had to keep turning my head, brushing any tickles of web on my neck, checking the ceiling and floor. They’re sneaky.

We ascended the Social In-cline. The houses grew and separated. Potted plants congregated in front gardens. The rain eased. Eventually we came back through the square and the bus hissed to a stop at Green Avenue. As I stepped down the driver gave me that smile again. The smile he always gives me when I get off at Green Avenue. The smile that knows it’s the same stop I got on at just half an hour ago.

Miss Hayes has a new theory. She thinks my condition’s caused by some traumatic incident from my past I keep deep-rooted in my mind. As soon as I come clean I’ll flood out all these tears and it’ll all be OK and I won’t be scared of

Them

any more. I’ll be able to do P.E. and won’t have any more episodes. Maybe I’ll even talk – and talk properly, with proper ‘S’s. The truth is I can’t think of any single traumatic childhood incident to tell her about. I mean, there are plenty of bad memories – Herb’s death, or the time I bit the hole in my tongue, or Finners Island, out on the boat with Sarah – but none of these caused the phobia. I’ve always had it. It’s

Them

. I’m just scared of

Them

. It’s that simple.

I thought I was in trouble the first time Miss Hayes told me to stay after class. She’d asked a question about

An Inspector Calls

and the representation of the lower classes and nobody had answered and so she’d asked me because she’d known I knew the answer because I’d just written an essay all about

An Inspector Calls

and the representation of the lower classes and I’d wanted to tell her the answer but the rest of the class had hung their heads over their shoulders and set their frowning eyes upon me so I’d had to just sit there with my head down, not saying anything.

Some of them started to giggle, which is a thing they like to do when I’m expected to speak and don’t. Some of them whispered. Carly Meadows said the word ‘psycho’, which is a word they like to use. Then the bell rang and everyone grabbed their things and ran for the door and Miss Hayes asked me to stay behind and I just sat there, waiting for a telling-off.