All Cry Chaos (16 page)

Authors: Leonard Rosen

"And finally, the country's smallest administrative units, the communes. There are some thirty-five thousand. From the looks of the coastline, these are the communes for Bretagne, Normandie, Nordpas-de-Calais, and Picardie."

Johnson found a magnifying glass in his forensics kit and paused over the communes. He moved the glass to the preceding images in the series and returned to the communes. "Each is a smaller version of the one before," he said. "The units repeat—though not exactly. They're related—"

"Geometrically."

"That's right. Let's see about this last one. It looks like a magnification of several communes. Fenster was thorough in laying out his sequences, in any event. Large to small to smallest." Johnson lifted the sixth and final image of the set off the wall and read the caption.

"A close-up?" asked Poincaré. "I wasn't aware of a smaller administrative unit than the communes. But it's the same geometry, no doubt." Johnson handed over the frame. On the reverse side was the following:

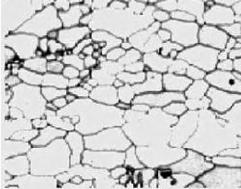

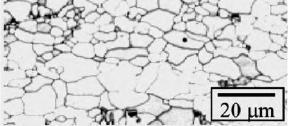

Grain boundaries, alloy of Al-Mg-Mn

Poincaré sat hard into Fenster's chair and waved off Johnson, who was about to caution him against contaminating potential evidence.

"What?" said Johnson.

"It's not a magnification of the communes or of any other map of France."

"So then?"

Poincaré looked to the wall, then back to the image in his hands. "The line in the box at the lower right shows a scale of 20 one-millionths of a meter in length. This is a photograph of a piece of metal under high-powered magnification. These are the crystal boundaries in an alloy of aluminum, magnesium, and manganese. The equation is a mathematical description of the alloy."

Johnson stepped around a chair. "Why," he asked, "should the crystal structure of a metal look like the communes or regions of France? Or the national boundary, for that matter?"

Poincaré was staring into the dead space at the center of the room.

That would be the right question

, he thought. Fenster was bending his mind in two directions to make a single point. First, the outlines of France's communes reproduced the fractal shape of the country's successively larger administrative units and then, improbably, the national boundary itself. It was not conceivable that eighteenth- century bureaucrats in Paris set the borders of 35,000 communes with an eye to reproducing the geometry of France's coastlines and mountain borders. Second, a photograph of a piece of metal under intense magnification showed the identical geometry. With colleagues Fenster would have used mathematics to make these comparisons. For lay people he had assembled this gallery, which was just as much an argument—the same argument he was set to make in Amsterdam in his talk on globalization.

That would be the right question

, he thought. Fenster was bending his mind in two directions to make a single point. First, the outlines of France's communes reproduced the fractal shape of the country's successively larger administrative units and then, improbably, the national boundary itself. It was not conceivable that eighteenth- century bureaucrats in Paris set the borders of 35,000 communes with an eye to reproducing the geometry of France's coastlines and mountain borders. Second, a photograph of a piece of metal under intense magnification showed the identical geometry. With colleagues Fenster would have used mathematics to make these comparisons. For lay people he had assembled this gallery, which was just as much an argument—the same argument he was set to make in Amsterdam in his talk on globalization.

Above the caption on the rear of the last image, Poincaré read three words:

The same name

. Curious, he thought. He returned the frame to its hook and flipped the preceding image. Above its caption:

The same name

. He moved down the line and found that each image on Fenster's walls had both an explanatory caption and, above that, the three words. Fenster had paired a cauliflower leaf with a river delta photographed from space. He had paired aerial photos of mountain ranges with lightning strikes and the root structures of plants. Most improbably, he had paired Ireland, as photographed from a NASA shuttle, with a thumbnail sized piece of lichen and the shadows of cumulous clouds on summer farmland. Each was a version of the others.

The same name

. Curious, he thought. He returned the frame to its hook and flipped the preceding image. Above its caption:

The same name

. He moved down the line and found that each image on Fenster's walls had both an explanatory caption and, above that, the three words. Fenster had paired a cauliflower leaf with a river delta photographed from space. He had paired aerial photos of mountain ranges with lightning strikes and the root structures of plants. Most improbably, he had paired Ireland, as photographed from a NASA shuttle, with a thumbnail sized piece of lichen and the shadows of cumulous clouds on summer farmland. Each was a version of the others.

"What's the point?" asked Johnson.

Poincaré was sure he didn't know. But one thing was certain: the waters in which he swam had gotten very deep, very quickly.

CHAPTER 15

"So explain this," said Johnson. "How could the state police have lifted such perfect prints from an apartment wiped down by three successive cleaning crews over three successive days? If I'm recalling the forensics report, they also found Fenster's DNA in dried urine. Am I to believe the man hired all this help and someone forgot to scrub his toilet?" Johnson removed tools from his forensics kit. "Give me thirty minutes," he said. "This Fenster-man's got my attention now."

At the bookcase, Poincaré reached for a volume at random:

Mahābhārata, Epic of Ancient India

.

A second:

The Aeneid

. Another, well known to him:

La Chanson de Roland.

On his haunches, he ran his fingers across the spines of some forty books: poetry, history, philosophy—not a volume of mathematics. Nor did Poincaré find translations. Only books composed in English were printed in English. The others, with Fenster's handwritten notes in the margins, were printed in their language of origin: Sanskrit, Latin, French, and Greek. Across the room, Johnson was standing on a kitchen chair, shoes covered with booties, to dust a light bulb.

Mahābhārata, Epic of Ancient India

.

A second:

The Aeneid

. Another, well known to him:

La Chanson de Roland.

On his haunches, he ran his fingers across the spines of some forty books: poetry, history, philosophy—not a volume of mathematics. Nor did Poincaré find translations. Only books composed in English were printed in English. The others, with Fenster's handwritten notes in the margins, were printed in their language of origin: Sanskrit, Latin, French, and Greek. Across the room, Johnson was standing on a kitchen chair, shoes covered with booties, to dust a light bulb.

"Have you ever tried screwing in a bulb without leaving prints?" he asked.

Poincaré had not. He returned to Fenster's reading chair to examine a cigar box left on the book shelf, which turned out to be a time capsule of sorts. Fenster had divided the contents into three neat sections: photos tied with string; a small plastic case with baby teeth; and a stack of medals with faded ribbons. He began with the photographs. Each showed Fenster between the ages of eight and fourteen, according to the date stamps, shaking the hand of a different adult beneath more or less the same banner: G

eometer of the Year, Advanced

Calculus Champion, Albert Einstein Young Scholar Award. H

e counted some two dozen photos in all, twenty-four awards distributed across seven years. Poincaré laid out the photographs chronologically and studied the progress of an awkward, lanky child growing before his eyes. In each image the boy looked pleased enough with his award, but also posed and uncomfortable in the extreme, his smile forced. The clothes fit poorly. Could the foster parents have pocketed the money provided by the state and kept the child in hand-me-downs? Across this entire span of years, the young Fenster looked pale beneath his halo of blond curls—even though he had won at least four of his awards during the height of summer. Poincaré held up one of the photos. "Agent Johnson," he said. "Could you take prints off this?"

eometer of the Year, Advanced

Calculus Champion, Albert Einstein Young Scholar Award. H

e counted some two dozen photos in all, twenty-four awards distributed across seven years. Poincaré laid out the photographs chronologically and studied the progress of an awkward, lanky child growing before his eyes. In each image the boy looked pleased enough with his award, but also posed and uncomfortable in the extreme, his smile forced. The clothes fit poorly. Could the foster parents have pocketed the money provided by the state and kept the child in hand-me-downs? Across this entire span of years, the young Fenster looked pale beneath his halo of blond curls—even though he had won at least four of his awards during the height of summer. Poincaré held up one of the photos. "Agent Johnson," he said. "Could you take prints off this?"

Johnson had climbed down off the chair and was now bent over Fenster's laptop. "Bring it over." he said.

"Who keeps your memories," asked Poincaré.

Johnson looked at him.

"Your memories of childhood—until you went off to college. Who keeps a record of your childhood, besides you?"

"My parents and brothers, I suppose. They have pictures—but mostly stories. Like the one of my brothers and me in a three-way boxing match. Instead of gloves, we used paintbrushes—we were painting an iron porch railing at the time. We each dipped two brushes in red Rust-Oleum and started jabbing. The one with the most paint on his face lost. That was me." Johnson chuckled at the thought. "My mother came tearing around the corner, screaming— but she had the good sense to take a picture, at least. She swore she was going to blackmail us when we got married."

"And has she?"

Johnson made a thumbs-up sign. "The funny part is, I was only five or six at the time and I don't actually remember getting painted. But I'm in the picture and my mother and brothers tell the story—so it happened, I suppose. . . . What are we talking about?"

Poincaré handed him the photo. "Fenster lived in five foster homes between the ages of four and fifteen. We have no idea about the circumstances of his birth, but he was apparently abandoned and then handed along until Princeton rescued him with a scholarship. The only proof he had of a childhood is in this cigar box. Besides the box, he had nothing—no stories, no boxing matches. Imagine a child that young knowing that if he didn't collect these things, no one would."

Poincaré returned the cigar box to the bookshelf, but Johnson called him back. "I need you to look at something," he said. "Fenster's laptop obviously won't boot because the state police took the hard drive. They left an evidence tag, so it's all kosher. Here's the thing—the slip of paper he taped along the side of the monitor. Are you related?" Using tweezers, Agent Johnson held before Poincaré a strip of clear tape laid over a narrower strip of paper on which Fenster, likely, had printed twelve words and a name:

Mathematics is the art of giving the same name

to different things.

— Jules Henri Poincaré

"My father's father's father," he said. The explosion in Amsterdam, on his watch; the death of a mathematician who happened to venerate his great-grandfather: the case, it seemed, had chosen him. "And no, I never met him."

"True?"

"It is. Jules was a mathematician—apparently a hero to Fenster."

"Well, this is strange."

Agent Johnson could not begin to guess.

"One more trick of the trade," Johnson said. "I dusted the outside of the tape for prints. This was likely wiped along with everything else. But there's no way to wipe the sticky

inside

of a piece of tape. Unless you're using tweezers or wearing gloves, you're going to leave prints on the adhesive when you lay it down."

inside

of a piece of tape. Unless you're using tweezers or wearing gloves, you're going to leave prints on the adhesive when you lay it down."

Other books

Epic Retold: The Mahabharata in Tweets by Chindu Sreedharan

Elsker - The Elsker Saga by S.T. Bende

Hollywood Star by Rowan Coleman

Finding North by Christian, Claudia Hall

Serpent and Storm by Marella Sands

Shadows of the Workhouse by Jennifer Worth

Jaffa Beach: Historical Fiction by Fedora Horowitz

A Higher Form of Killing by Diana Preston

The Rolling Stones by Robert A Heinlein

The Witchfinder by Loren D. Estleman