All Hell Let Loose (13 page)

Read All Hell Let Loose Online

Authors: Max Hastings

In the May 1940 BEF, John Horsfall deplored a lack of good maps; failure to cover the retreat by local counter-attacks and inflict substantial damage on the German spearheads; to deploy artillery effectively; or adequately to brief those at the sharp end: ‘Our soldiers just need to know in simple terms what they have to contend with.’ Horsfall and his comrades became bewildered and disgusted by their long trek back from Belgium and through north-eastern France, during which they watched a substantial part of the army, and most of its commanders, fall apart. ‘It was a rotten march,’ he wrote, ‘and the [Fusiliers] were progressively broken up by lost and sometimes disordered fragments of other units surging in on us from the side roads … There was over-much to brood upon … One could not fail to be aware of the loss of grip somewhere in our army. Our men knew it soon enough, and it became the task of the officers to stifle the subject – or laugh at it … Something pretty bad was happening. But it was no more the fault of our regiments than the shambles of the Crimea had been … I saw no reason … why that critical retreat was not effectively controlled.’

Meanwhile, French commanders appeared to inhabit a fantasy world. Gamelin’s staff officers marvelled to see him at lunch in his headquarters on 19 May, joking and making light conversation while his subordinates despaired. At 2100 that night, about the time the first panzers reached the Channel at the mouth of the Somme, on Reynaud’s orders Gamelin was replaced as France’s military leader by seventy-three-year-old General Maxime Weygand. The new supreme commander realised that the Allies’ only chance was to launch counter-attacks from the south and north against the German flanks in the vicinity of Arras, to break the encirclement of Belgium and north-east France. Sir Edmund Ironside, the British CIGS visiting from London, reached the same conclusion. Meeting two French generals, Gaston Billotte and Georges Blanchard, at Lens, Ironside was disgusted by their inertia. Both men were ‘in a state of complete depression. No plan, no thought of a plan. Ready to be slaughtered. Defeated at the head without casualties.’ Ironside urged an immediate attack south towards Amiens, with which Billotte promised to cooperate. Ironside then telephoned Weygand. They agreed that two French and two British divisions would attack next morning, the 21st.

Yet Gort never believed the French would move, and he was right. When the two weak British formations advanced next day they did so alone, and without air support. The Germans were initially thrown into disarray as Gort’s columns struck west of Arras. There was fierce fighting, and the British advanced ten miles, taking four hundred prisoners, before the attack ran out of steam. Erwin Rommel, commanding a panzer division, took personal command of the defence and rallied his surprised and confused units. Matilda tanks inflicted significant German losses, killing Rommel’s ADC at his side. But by then the British had shot their bolt; the attack was courageously and effectively delivered, but lacked sufficient weight to be decisive.

On the morning of that same day, the 21st, even as the British were moving towards Arras, Weygand set off from Vincennes for the northern front, in hopes of organising a more ambitious counterstroke. After waiting two hours at Le Bourget for a plane, the C-in-C’s trip descended into farce. Arriving at Béthune, he found the airfield deserted save for a single scruffy soldier guarding petrol stocks. This man eventually drove the general to a post office where he was able to telephone the army group commander, Billotte, who had spent the morning searching for Weygand around Calais. The C-in-C, after pausing for an omelette at a country inn, used a plane to reach the port, then crawled by car along roads jammed with refugees to meet Belgium’s King Leopold at Ypres town hall. He urged the monarch to hasten his army’s retreat westward, but Leopold was reluctant to abandon Belgian soil. Billotte said that only the British, thus far scarcely engaged, were fit to attack. To Weygand’s anger – for he wrongly saw a snub – Lord Gort did not join the meeting.

When the BEF’s commander belatedly reached Ypres, without much conviction he agreed to join a new counter-attack, but said that all his reserves were committed. He never believed any combined Anglo-French thrust would take place. Weygand later claimed that the British were bent on betraying their ally: this reflected a profound French conviction, dating back to World War I, that the British always fought with one eye on their escape route to the Channel ports. The British, in their turn, despaired at French defeatism; Weygand was thus far right, that Gort believed his allies hopelessly inert, and was now set upon salvaging the BEF from the wreck of the campaign. Later on that bleak night of 21 May, Billotte was fatally injured in a car crash, and two days elapsed before a successor was appointed as Northern Army commander. Meanwhile, the breakdown of Allied command communications became comprehensive. After a meeting with the French army group commander the previous day, British CIGS Sir Edmund Ironside wrote: ‘I lost my temper and shook Billotte by the button of his tunic. The man is completely beaten.’ Gort told King Leopold on the evening of the 21st: ‘It’s a bad job.’ At 1900, Weygand left Dunkirk by torpedo boat in the midst of an air raid, eventually regaining his headquarters at 1000 next morning. Throughout every hour of his futile wanderings across northern France, German tanks, guns and men continued to stream north and west through the great hole in the Allied line.

The supreme commander now succumbed to fantasy: reporting to Reynaud on the morning of 22 May, he seemed in almost jaunty mood. ‘So many mistakes have been made,’ he said, ‘that they give me confidence. I believe that in future we shall make less.’ He assured France’s prime minister that both the BEF and Blanchard’s army were in fine fighting trim. He outlined his planned counter-attack, and concluded equivocally: ‘It will either give us victory or it will save our honour.’ At a meeting in Paris on 22 May with Churchill and Reynaud, Weygand exuded optimism, claiming that a new army of almost twenty divisions would conduct the French counter-attack from the south to restore the link with the BEF. Both the army and the attack, however, were figments of his imagination.

On the night of the 23rd, Gort withdrew his forces from the salient they held at Arras. This caused the French to assert that the British were repeating their selfish and pusillanimous behaviour of 1914. Gort’s decision represented only a recognition of reality, but Reynaud failed to tell Weygand that the British were preparing to evacuate the BEF. Gort told Admiral Jean-Marie Abrial, commanding the Dunkirk perimeter, that three British divisions would help to screen the French withdrawal. After Gort’s departure for England, however, his successor in command, Maj. Gen. Harold Alexander, declined to make good on this commitment. Abrial said: ‘Your decision dishonours Britain.’ Defeat prompted a welter of such inter-Allied recriminations: Weygand, told of the Belgian surrender on 28 May, expostulated furiously: ‘That king! What a pig! What an abominable pig!’

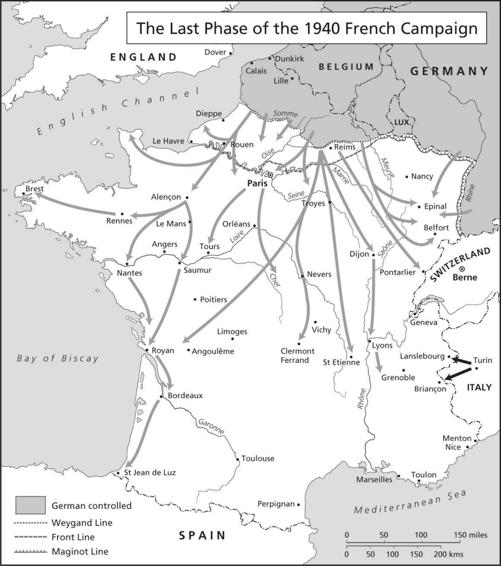

The Last Phase of the 1940 French Campaign

The British, meanwhile, had begun to evacuate the BEF from the port and beaches of Dunkirk. ‘It was evident to one and all that a monumental military disaster was in progress,’ Irish Fusiliers officer John Horsfall wrote with weary resignation. ‘Therefore we could take refuge in history, knowing that this was not only to be expected but actually the commonplace experience of our army when tossed recklessly by our politicians into European war.’ Sergeant L.D. Pexton was one of more than 40,000 British soldiers taken prisoner, after a rearguard action near Cambrai in which his unit was overrun: ‘I remember the order “Cease Fire” and that the time was 12 o’clock,’ he wrote afterwards. ‘Stood up and put my hands up. My God how few of us stood up. I expected my last moments had come and lit a fag.’

The Dunkirk evacuation was announced to the British public on 29 May, when civilian volunteers from the Small Boat Pool joined warships rescuing men from the beaches and harbour. The Royal Navy’s achievement during the week that followed became the stuff of legend. Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay, operating from an underground headquarters at Dover, directed the movements of almost nine hundred ships and small craft with extraordinary calm and skill. The removal of troops from the beaches in civilian launches and pleasure boats forged the romantic image of Dunkirk, but by far the larger proportion – some two-thirds – were taken off by destroyers and other large vessels, loading at the harbour mole. The navy was fortunate that, throughout Operation

Dynamo

, the Channel remained almost preternaturally calm.

Soldier Arthur Gwynn-Browne poured out in lyrical terms his gratitude for finding himself returning home from the alien hell of Dunkirk: ‘It was so wonderful. I was on a ship and any ship yes any ship is England. Any ship yes any ship I was on a ship and on my way to England. It was wonderful. I kept quite still and the sea breezes I swallowed them, no smoke and burning and fire and thick grey oil smoke hazes, but sea breezes. I swallowed them they were so clean and fresh and I was alive it was so wonderful.’ Many men arrived in England fearful of their reception, as flotsam from one of the greatest defeats their country had ever suffered. A company quartermaster, Walter Gilding, wrote: ‘When we went ashore I thought everybody was going to shoot us, especially as being regular soldiers, we’d run away … But instead of that there were people cheering and clapping us as if we were heroes. Giving us mugs of tea and sandwiches. We looked a sorry sight, I think.’

John Horsfall had the same experience: ‘At Ramsgate we met for the first time the unbelievable feat of improvisation achieved by the armed services and civil authorities acting in concert. Here was Britannia to greet us with the wand of a fairy and her mantle of magic; here, too, was a brief flash of history. Dimly conscious of it, we were deeply touched and knew immediately the national mood of defiance which brought down Napoleon and would destroy Hitler too. The warmth of the reception in this ancient seaport was inspired … An endless series of trains were awaiting and charming ladies with tea and other comforts. But fatigue and reaction were hard on the emotions, and we may have been less than responsive.’

The legend of Dunkirk was besmirched by some uglinesses, as is the case with all great historical events: a significant number of British seamen invited to participate in the evacuation refused to do so, including the Rye fishing fleet and some lifeboat crews; others, after once experiencing the chaos of the beaches and Luftwaffe bombing, on reaching England refused to set forth again. While most fighting units preserved their cohesion, there were disciplinary collapses among rear-echelon personnel, which made it necessary for some officers to draw and indeed use their revolvers. For the first three days, the British were content to take off their own men, while the French held a perimeter southwards and were refused access to shipping. On at least one occasion when

poilus

attempted to board vessels, they were fired on by disorderly British troops. Only when Churchill intervened personally did ships begin to take off Frenchmen, 53,000 of them after the last British personnel had been embarked. Most subsequently insisted upon repatriation – and thereafter found themselves forced labourers in Germany – rather than remain as exiles in Britain.

A British soldier based at Dover barracks, Donald McCormick, found little romance in his own contribution to the evacuation, described in a letter home on 29 May: ‘We … are woken & taken down to the docks at 1.45am, where we undergo physical strain & mental torture until 8.30 carrying corpses about & loose hands & brains are all in the day’s work. I feel very upset & sometimes feel like crying when I am down there. It is all so pointless & I hate the callousness with which it is treated by the majority of our people who chiefly go down to see what they can pinch in the way of cigarettes & money.’

The navy suffered severely at Dunkirk, losing six destroyers and a further twenty-five damaged. Its worst day came on 1 June, when three destroyers and a passenger ship were sunk by air attack and four others crippled. Thereafter, the Admiralty felt obliged to withdraw its large warships from the evacuation. The RAF was often cursed by soldiers and sailors for its supposed absence from the skies; every man at Dunkirk learned to dread the repeated Stuka attacks. Yet Fighter Command made a major contribution to holding the Luftwaffe at bay, at the cost of losing 177 aircraft during the nine days of the evacuation. As the Germans sought to impede

Dynamo

, their pilots declared themselves more hard-pressed by fighters than at any time since 10 May. The Luftwaffe’s effort against the departing British fell far short of Goering’s hopes and promises, and this was as much due to the RAF as to its own bungling. After 1 June the Luftwaffe redeployed most of its aircraft to harry the French, making the final phase of the evacuation much less costly than the first.

The towering reality was that the BEF got away. Some 338,000 men were brought back to England, 229,000 of them British, the remainder French and Belgian. The withdrawal and evacuation were widely held to be Gort’s personal triumph; but while the C-in-C indeed gave appropriate orders, success would have been unattainable had not Hitler held back his tanks. It remains unlikely, though just plausible, that this was a political decision, prompted by a belief that restraint would render the British more susceptible to peace negotiations. More credibly, Hitler accepted Goering’s assurance that the Luftwaffe could finish off the BEF, which no longer threatened German strategic purposes; and the panzers needed rapid refit before being urgently redeployed against Weygand’s forces. The French First Army conducted a brave stand at Lille, which contributed importantly to holding the Germans off the Dunkirk perimeter; it was understandable that British soldiers showed bitterness towards their allies, but Churchill’s army had performed little better than Reynaud’s in the Continental campaign.