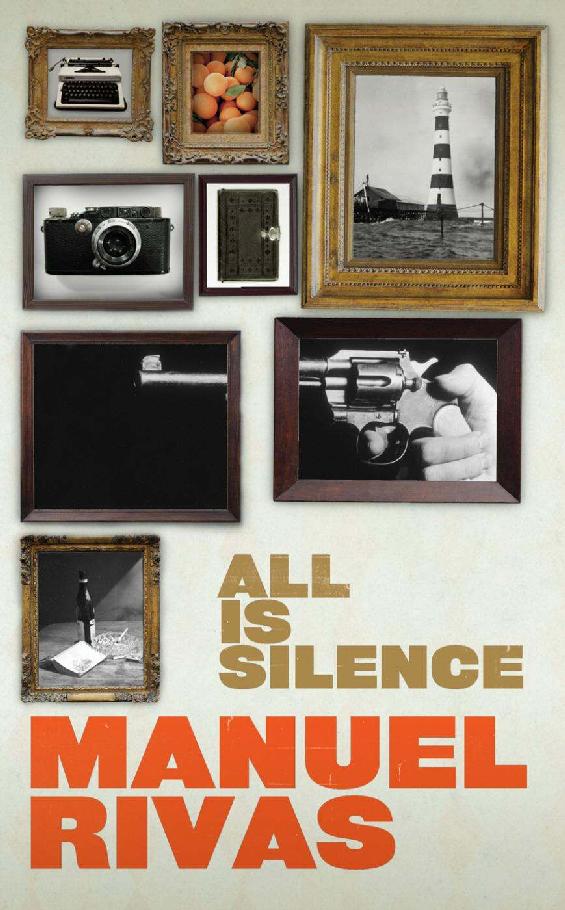

All Is Silence

Authors: Manuel Rivas

Contents

Fins and Brinco are best friends, and they both adore the wild and beautiful Leda. The three young friends spend their days exploring the dunes and picking through the treasures that the sea washes on to the shores of Galicia.

One day, as they are playing in the abandoned school on the edge of the village, they come across treasure of another kind: a huge cache of whisky hidden under a sheet. But before they can exploit their discovery a shot rings out, and a man wearing an impeccable white suit and panama hat enters the room. That day they learn the most important lesson of all: that the mouth is for keeping quiet.

Manuel Rivas was born in A Coruña in 1957. He writes in the Galician language of north-west Spain. He is well known in Spain for his journalism, as well as for his prize-winning short stories and novels, which include the internationally acclaimed

The Carpenter’s Pencil

and

Books Burn Badly

. His works have been translated into more than twenty languages.

Jonathan Dunne translates from Bulgarian, Catalan, Gallician and Spanish. He has translated six books by Manuel Rivas into English. He is the editor and translator of the two-volume

Anthology of Galician Literature 1196–1981/1981–2011

and of the

Poetry Review

supplement

Contemporary Galician Poets

. His recent translations include

At the End of the World: Contemporary Poetry from Bulgaria

.

Fiction

The Carpenter’s Pencil

Butterfly’s Tongue

Vermeer’s Milkmaid

In the Wilderness

Books Burn Badly

Poetry

From Unknown to Unknown

The Disappearance of Snow

Manuel Rivas

Translated from the Galician

by Jonathan Dunne

1

‘

THE MOUTH IS

not for talking. It’s for keeping quiet.’

This was one of Mariscal’s sayings, which his father repeated like a litany and Víctor Rumbo – Brinco – recalled when the other boy saw with amazement what was in the strange package he’d pulled out of the basket and asked what he wasn’t supposed to.

‘What’s that then? What are you going to do?’

‘They have mouths, and speak not,’ replied Brinco laconically.

The tide was out, or thinking of coming in, the calm of the waters shocked and shining, which seemed somehow strange. There were the two of them, Brinco and Fins, near the breakwater formed by the rocks, next to the lighthouse on Cape Cons, and not far from the stone crosses that commemorate lost sailors.

In the sky, the beam from the lighthouse acting as epicentre, the seagulls pecked at the silence. There was a mocking wisdom in the way these birds kept watch. An alert grumbling. They moved off in order to come closer, drawing circles that were ever more insolent. They took this liberty, sharing with abandon a secret the rest of existence chose to ignore. Brinco glanced over at them, amused by their scandal. He knew he was the cause of their excitement. They were waiting for something. A definitive sign.

‘My dad knows the names of all these rocks,’ said Fins in an attempt to detach himself from the course of events. ‘The ones you can see and those you can’t.’

Brinco had learned by now how to show contempt. He loved the taste of sentences that stung the palate.

‘Rocks are just a bunch of old rocks.’

He grabbed the stick of dynamite, which was already fitted with a fuse. As if he knew what he was doing.

‘Your dad may be a good sailor, that I do not deny. But now you’re going to see some real fishing.’

He finally set light to the fuse. Showed enough composure to hold the stick of dynamite in the air, in front of Fins’ face. And then chucked it skilfully over the top of the stone crosses. After a while they heard it explode in the sea.

They waited. The gulls grew more excited, a pack on the wing, egging Brinco on with their screams, celebrating each leap he made on the rocks. Fins kept his eyes firmly on the sea.

‘This will be a mark of fear now.’

‘You what?’

‘The fish won’t come back. Wherever someone sets off dynamite, they refuse to return.’

‘Why? Because your dad says so?’

‘Everybody knows that. It’s because of all the mess.’

‘Right,’ said Brinco mockingly.

In the Ultramar he’d heard similar things and knew how best to respond. ‘I suppose you’re going to say now that fish have memory.’

He smiled suddenly. One force overcame another inside him and it was this that articulated the smile. What came into his mouth was another saying of Mariscal’s. Guaranteed to produce a victory with Fins Malpica looking increasingly on the back foot, pale and subdued as a penitent. The son of the bearer of the cross.

‘If you stay poor for long,’ said Brinco with measured emphasis, ‘you end up shitting white like a seagull.’

He knew that each of Mariscal’s sayings would sweep the board. Never failed. Though it bothered him having such a source of inspiration. There’s something funny about Mariscal and his maxims. Even if he closed his ears, they’d still lodge inside him. What gives a cherry its stalk? That’s another of his. Another one that lodged inside him. Never fails.

Brinco and Fins sat down on a rock and stuck their bare feet in a tidal pool. In this aquarium the only life on view was the animal garden of anemones. They played at drawing their toes closer, a movement which made the false flowers shake their tentacles.

‘Bastards,’ said Brinco. ‘They look like flowers, but they’re really leeches.’

‘Their mouth is also their bottom,’ said Fins. ‘It’s the same hole, their mouth and bottom.’

The other boy stared at him in amazement. Was about to proffer some rebuke. But thought better of it and remained quiet. Fins Malpica knew much more than he did about fish and animals. And all the rest. At least in school. So Brinco decided to catch something in the pool and stuff it inside his mouth. He closed his mouth and kept his face swollen like a lung. Then he opened it and produced a tiny, live crab on his tongue.

‘How long can you hold your breath?’

‘I don’t know. About half an hour or so.’

Fins became thoughtful. Smiled inside. This was the game with Brinco, you had to let yourself lose in order to keep him happy. Pretend you were a fool.

‘Half an hour?’ said Fins. ‘That’s not much.’

It was the first time they’d laughed together since reaching Cape Cons. Brinco stood up and gazed out to sea. With this movement, shielding his eyes with his hand, the din in the sky grew louder. The fierce screams pierced the atmosphere at its weakest point. The first dead fish turned up in the foam, as if parboiled by the sea. Brinco goes after them with his net. Their intestines are all over the place. In the attritional palm of his hand, the contrast between the silver gleam of their skin and the blood of their gills is greater.

‘You see? Now is that, or is that not, a miracle?’

HE WAS THE

son of Jesus Christ. The son of Lucho Malpica. People would say, ‘That’s Lucho’s son’ or, identifying him with his mother, ‘That’s Amparo’s son.’ But he was better known because of his father. Among other things, his father had spent the last few years playing Christ on the day of the Passion, Good Friday. When he was younger, he’d taken the part of a Roman soldier. He’d even held the whip with which to lash the back of Edmundo Sirgal, the Christ before him, who’d also been a sailor. But Edmundo had left for the oil rigs in the North Sea. The first year he’d managed to return in order to be crucified. But then there’d been some problem. People leave and sometimes you lose touch. What was needed was a new Christ, and Lucho Malpica was the obvious choice. There was another bearded gentleman who could have done it, Moimenta, but he had one Michelin too many. As the priest pointed out, ‘Christ, Christ can be anyone, but he shouldn’t be fat. A good Christ isn’t fat, he’s all fibre.’ And there was Lucho Malpica, strong and thin as a rake. Of the same constitution as the wooden cross on his shoulder.

‘The Companion? He’s half pagan, Don Marcelo,’ said a bore from the confraternity.

‘Like them all. But the way he plays Christ is first class! Straight out of Zurbarán!’

Malpica didn’t stay still. Burned with speed. Brave as well, his guts in the palm of his hand. His son, Félix – Fins to us – was more like his mother. A bit nostalgic. He had his days, of course. We all have our spring tides and neap tides. He had those days when he turned into a zombie, fell quiet. Absorbed in silence.

The point is he was respectful towards his father, but had his confidence. He never asked for his father or Dad. He asked for Lucho Malpica. Outside the house, this sailor was a kind of third man, something separate from son and father. The boy was forced to protect him. Look out for him. Whenever he saw him coming home drunk, he’d run to the door and help him upstairs, put him to bed like a stowaway, so there wouldn’t be trouble at home; his mother had no time for these minor shipwrecks. Once, on the road to Calvary, his mother had said, ‘Don’t call him Lucho when he’s carrying the cross.’ For Fins, as a boy, it’d been an honour to watch his father being crucified with the crown of thorns, the smear of blood on his forehead, that blond beard, tunic with the golden belt, sandals. His attention was drawn especially to the sandals, since this wasn’t a type of footwear worn by men in Noitía. There were women who wore them in summer. One holidaymaker in particular who stayed with her husband at the Ultramar. And painted her toenails. Nails that shone with oyster enamel. Nickel-plated nails. All the boys roundabout, pretending to scrabble on the ground for coins. All because of the woman from Madrid with the painted toenails.

Christ’s toes had tufts of hair, nails like limpets, and, despite the sandals, doubled over to cling to the ground as when walking on the surface of rocks. Before the procession he called Fins to one side: ‘Pop over to the Ultramar and tell Rumbo to give you a bottle of holy water.’ He already knew this wasn’t water from the stoup. No, he didn’t say anything to his mother. No need to worry her. He’d done the job of Cana before. So he applied grease to his shins and ran as fast as he could. On the way back, he decided to take a sip. Just a moistener. To see what it tasted like. If they all swore by it, there must be something about it. And he could do with a pick-up on a day like this. He felt his entrails, and the reverse of his eyeballs, ignite. He breathed in deeply. As the fresh air doused that inner fire, he corked the bottle, wrapped it in the brown paper and pleaded with his feet to arrive in time before his father had lifted the cross.