All of the Above (10 page)

Principal called me into his office and tried to find out what I knew. “Other people here at Washington may trust you, James,” he said, leaning across his desk to stare at me. “They may think you've mended your ways. But I know better. You come from a rough crowd, and it wouldn't surprise me if you had some hand in this.”

How's telling people like you what happened gonna help me, fool? That's what I'd like to say to Principal. You gonna snap your fat white fingers and make everything better? Why don't you step into my shoes for a while? I got a brother who's no brother, an apartment with no food, my brother's friends who are just looking for a reason to come after me … and that's only the beginning of all my problems. Why'd I be stupid enough to cause more trouble and spill my guts to you?

So I tell Principal I don't know nothing, even though I do.

They try all kinds of bribes and threats to get other kids to talk—all-school detention, canceling a Friday basketball game, offering a $100 reward—but nobody confesses anything because I'm the only one who knows that it was Markese and his friends who wrecked the project, and even though I'd like to see them have to glue the whole thing back together piece by piece for the next fifty years, I still keep my mouth shut.

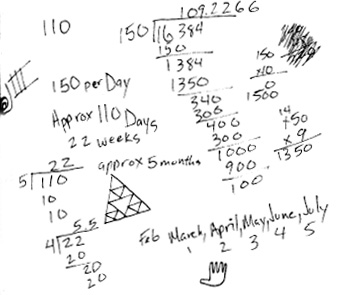

But in English class, while Clueless Sub is reviewing what we know about clauses, I start thinking about how long it would really take to rebuild. Eight months? Six months?

“James, tell us one thing you know about clauses,” Clueless Sub says.

“Santa Claus. That's all I know, man,” I answer.

And Clueless Sub says, “Get out in the hall, young man, and don't come back until you're ready to respect my authority.”

Yeah, right …

So I sit in the hall and try to figure out how many days we would need if we started the project again. I tear off part of a sheet of notebook paper that's sticking out of somebody's locker and pick up a chewed-up pencil that's sitting under the water fountain. It takes me about half an hour to figure out all the dividing and carrying to do. Math ain't my thing, so I don't know why I'm even trying. Nothing else to do in the hall, though, and I'm not going back to Clueless Sub.

My figuring says if we could make 150 pieces a day, divided into 16,384—the number of pieces needed for the record—it would take us about 110 days. Meaning, if we started now and worked five days a week, we could probably be done sometime in July. Which doesn't seem that impossible as long as you don't look outside and realize it's only the beginning of February, and there's a blizzard outside, and half the winter is still left to go.

At lunchtime, I go and find Mr. Collins. He's eating lunch at his desk.

“This right?” I say, pushing my paper in front of him.

“What were you trying to figure out?” he asks, squinting at my scrawled numbers.

“How long would it take to rebuild? Is a hundred and ten days right or not?”

Collins gives me a strange look, like he's surprised at something, but I don't know what.

He folds the paper in half and hands it back to me. “Think about how hard it would be to start all over again,” he says, beginning to clean up his lunch. “Is that what you really want to do, James?”

He crumples his sandwich bag and sweeps up the crumbs from his desk with his hands. “But you're right,” he continues. “If we had the time and made a hundred and fifty pieces a day, it would probably take about one hundred and ten days.”

“What if I get the other people to come back?” I ask.

Collins shakes his head and says it's too much work.

“I don't care, I'm gonna try. You give me some paper and I'll start on the new pieces tonight,” I insist.

I walk toward the cupboard where he keeps the stacks of colored paper. “I'll make one hundred and fifty by myself tonight, you just wait and see.”

“James …”

Collins tries to get me to give up, but I won't. All those eyes that are watching me are raising their eyebrows and looking sideways at each other, not sure what I'm gonna do next. Keep it that way.

Don't know what's wrong with kids these days. They're soft. When times are tough, they melt like butter in the hot sun.

A couple of days after talking to my friend Joe at the school, I ask Marcel when he's gonna rebuild that project, and he tells me he's not.

That's what I mean. Soft.

When I was growing up, kids were tougher. Had to be. We were getting married at eighteen or nineteen and getting sent off to war. It wasn't no picnic.

“You just gonna let the people who ruined your project win?” I turn to look at Marcel, who is standing by the counter while I'm shredding some pork for barbecue sandwiches.

Marcel gives me that shrug of his that I don't allow.

I get in his face because I won't stand for that attitude. “You better abandon that rude habit of yours and show me some respect,” I warn him, still holding the knife in one hand. “Willy Q's son don't act that way. You disagree with me, you say it to my face. You don't shrug your shoulders at me, you understand?”

Marcel says he does, but I can tell it won't last. I repeat my question. “You gonna let the people who ruined your project win?”

Marcel answers as slow as he can, still being disrespectful, in my opinion.

“Maybe,” he says.

He's playing with the coffee stirrers on the counter, making squares and triangles. Doesn't even try to look at me while he's talking.

I give Marcel the list of all the times I could have given up. I count them one by one on my fingers: when my daddy died when I was eight years old, when we lost everything we had in a fire and we had to live in a shelter for three months, when I got drafted, when three of my buddies were killed in Vietnam, when I had to turn my drinking habits around, when the first barbecue place I owned got burnt to the ground and I lost all my money.…

“But I never let the enemy win,” I say to Marcel. “Death, fire, booze, the Viet Cong, none of them could beat this man”—I point at my chest—“Willy Q. Williams.”

“And you ain't gonna give up either,” I tell him. “Ain't gonna stand for having no son like that. Williams people don't give up. Your granddaddy didn't give up, I didn't give up, and you ain't going to either.” I can feel myself getting emotional, thinking about my own daddy and all, so I try to finish up talking before I do.