All Souls (33 page)

Authors: Michael Patrick MacDonald

In the summer of 1996, Citizens for Safety was getting ready to organize its fourth annual gun buyback program. One day I was walking by the courthouse on Broadway, reading about Brian Havlin, a neighbor who'd been ambushed in the Old Harbor Project and shot nine times after an argument. As I passed the courthouse, I saw a redheaded woman pacing. I knew that face. She looked like Ma after losing Frankie, with anger and sadness welling up in tears that refused to fall while her daughters stood by her. “Are you Mrs. Havlin?” I asked.

Kathy Havlin started coming to our South Boston Vigil Group meetings along with her three daughters. She was angry about the hypocrisy of our politicians, who'd only sent her their sympathies once they found out how well thought of Brian was and that his murderer was a junkie no one liked anyway. She also vented her fury at the priest who'd come to her project apartment, discovered she was a single mother, and looked around the room asking, “Do you work or anything?” She was working on bringing the murderer to justice and wanted to shut down the bar where the fight had started. She also wanted to do something about guns on the street. Before long she was meeting me at the end of her long work day, showing up on Geneva Ave. in the heart of black Dorchester, to hand out gun buyback fliers with Tina Chery, who'd lost her son Louis to gunfire on that street. Kathy walked up to tough-looking black teens hanging out on corners and pleaded with them to spread the word about the buyback.

By 1996, our buyback program was led by survivors from every neighborhood in Boston. Terri Titcomb, whose son Albie had recently been shot in Charlestown over a fifty-dollar drug debt, led the press conference, her back and shoulders buttressed by outstretched hands of all colors. She asked parents to turn in guns, teenagers to turn in guns, and legislators to make stricter laws on the gun industry.

That buyback, we took in fewer guns, and the Boston Police Department didn't see any reason to continue the project. With their growing emphasis on “zero tolerance” policing and suppression tactics, the cops weren't impressed by our multiracial mumbo jumbo. But as we'd found year after year, the tougher guns were coming in with each successive buyback. I had the buyback hotline in my apartment in Southie, so I knew where the guns were coming from, and they weren't coming from little old widows, as the cops liked to say. I got directly involved in a number of turn-ins, one from a former gang member, another from a thirteen-year-old girl hiding a gun for her boyfriend until he got out of DYS, and one from a murder victim's mother, who'd been hell-bent on revenge until she'd become one of the program's spokespersons.

On the last day of the buyback, I received a call from a priest in Dorchester. A thirteen-year-old had given him a .357 Magnum to turn in. I told him where and how to turn it in, and hung up my last buyback call, having helped to destroy 2,901 guns. And I remembered Tommy Viens, the reason I got involved in the first place.

That year, Ma won the suit in Colorado, setting a precedent to challenge other states that had been getting away with violating the Americans with Disability Act. Kathy was still talking to herself, scrawling the names of her old gang from 8th Street on random pieces of paper and Styrofoam cups, along with the old slogans:

RESIST, NEVER

, and

HELL NO WE WON'T GO

. But now she was eligible for services, therapy, and day trips with caretakers. Joe, as usual, was working two jobs, and was looking to buy a third house in the Colorado mountains. Maria was entering the second grade and winning swim meets at the local recreation center. Seamus and Stevie were going on to college at the University of Colorado. Johnnie had moved to Maine after all of Frankie's friends had been locked up and he got tired of Southie. Mary was still working in the operating room at the City Hospital, had saved for a house in Quincy, and was raising her third child with Jimmy.

And I was in Southie, watching in the dark as hundreds filed into our vigil at the Gate of Heaven Church. They'd stood in line in defiance of the strong winds and pouring rain, and walked past the bagpipers playing “Amazing Grace.” They were children, teenage friends of kids who'd committed suicide, mothers whose kids had been murderedâsome as long as fifteen years agoâolder men and women with canes, pulling their way up the slippery railing one step at a time with tears and rain streaking their ruddy cheeks. A few black and Latino women got out of taxis they'd taken through the storm, braving the town they'd always been warned not to enter, and being embraced by women like Kathy Havlin and Theresa Dooley. I'd been scared of this day, the day when we'd all do our small part in breaking the silence, by saying names some people wanted us never to mention.

That's how I found myself staring out at a sea of faces, looking for my brothers among the living and the dead. I was looking for the truth about their lives and about their deaths. Like me, everyone at that night's vigil will forever be looking for the truth in Southie, where nothing's what it seems.

Standing at the altar, I at last felt I might be able to reconcile myself with all my memories of confusion, bloodshed, and betrayal. And that I could do it with love. I love my family. And I love Southie.

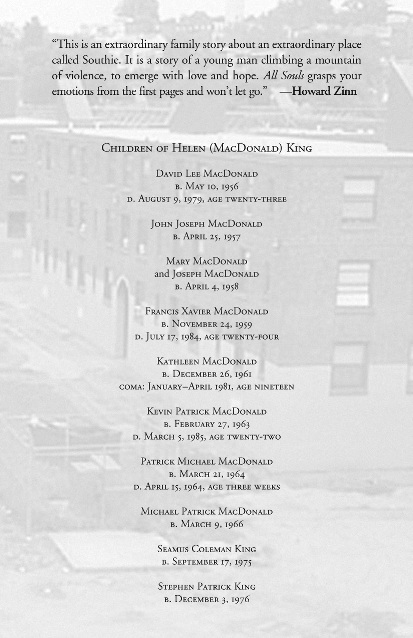

“These candles burn for my brothers.” I stopped and took a deep breath. Then I spoke up. “Davey, Frankie, Kevin, and Patrick ⦔

And for all souls.

I

AM DEFINITELY BLESSED TO LIVE IN SOUTH BOSTON,

among some of the world's most brilliant, loving, and tough people. Thank you to the overwhelming majority of good people in the town, who, through some of the worst forms of oppression by all sides of the political, social, and criminal spectrum, still believe in the village ideal.

A million and one thanks to my editor, Deanne Urmy, for being the champion archangel of

All Souls

, and for her brilliant and compassionate guidance through every painful and personally redemptive sentence. And to my whole team at Beacon: Helene Atwan, Amy Caldwell, Tom Hallock, and Pam MacColl. Special thanks also to Kathie Mainzer, for acting as my production coach and mentor, urging

All Souls

to life. Thank you to the many friends who have given advice on my manuscript through various stages and encouraged me to keep writing: Margaret Lazarus, who always challenged me to maintain and nurture the voice I'd found, and Renner Wunderlich, Maire Murphy, Judith Gaines, Brian MacQuarrie, Jimmy Tingle, Maureen Dezell, Jeff Lowenstein, Channing Thieme, Jill Cunniff, and Bob Cunniff.

Thanks to Barbara Hindley for being the connection that made

All Souls

possible, and to my agent John Taylor “Ike” Williams for making many more.

I am grateful also to all those who kept me connected to the world, and never let me fall into the pit of writer's isolation. Your good thoughts, support, and company sustained me through what could have been a very lonely process: Reme Del Valle, my cousin Maureen Kelly, Clara and Bill Wainright, Rachael and Madeleine Steczynski, Libby McClaren, Sr. Ann Fox and Barry Hynes, Lew Dabney, the Boston Gun Buyback's founding father, Molly Baldwin and the young people at ROCA Inc., Charlie Rose and Carol Downes, Leo Rull, Jerry Hurley, Paul and Mary Ulrich, Theresa Dooley (a South Boston mother whose presence in my life continues to inspire my work), Sandy King, Elizabeth Bartholomew, Lois Molinari, Pam and Billy Enos, Helen Kearns, Terri and Al Titcomb, Tina Chery, Cathy Tyler, Audrey Smith, Maryann Crayton, Cookie and Tipp Harris, Carol Ann Mehan, Katie Flaherty, the South Boston Vigil Group folks, the Charlestown After Murder Program, Brian Murphy, the Riordans from Castle Island in Kerry, the McShanes from Keady in Armagh, and to the residents of the Garvaghy Road in Portadown.

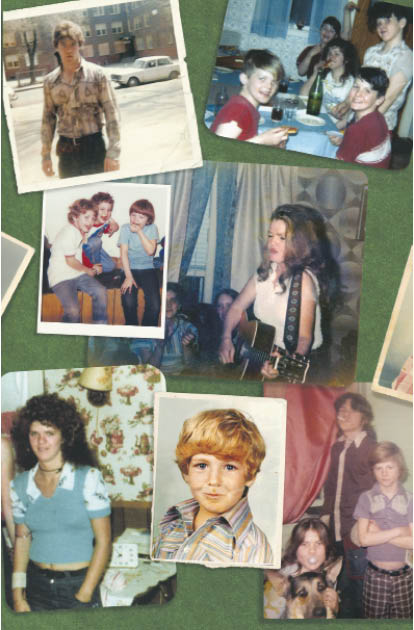

To all my family: Davey, Johnnie, Joe, Mary, Frankie, Kathy, Kevin, Patrick, Seamus and Steven, and Ma, who talked to me through all the relevant and painful stories, and who every day bears witness to the boundless strength of God's human creation.

I am fortunate to know some incredible young people, my adopted sisters and brothers in Southie who listened to stories or eagerly read

All Souls

at every stage, and whose laughter and tears told me I was doing the right thing: Steven Kozlowski, Billy Coleman, Jimmy Connolly, Justin Downey, Katie Heiskell, Jen McAuliffe, Ronnie Sullivan, John Ulrich, Susan Ulrich, and Tara Van Osdol.

For me, the urgency of this book was emphasized by the town's recent suicides, when hundreds of teenagers attempted suicide, and six young people who saw no other “way out” killed themselves, leaving a void in the lives of friends and neighbors: Kevin Geary, Tommy Mullen, Duane Liotti, Jonathan Curtis, Tommy Deckert, and Kevin Cunningham. You are sorely missed. Thank you to the young people of Southie who will honor their friends' memories by choosing to live.

Michael Patrick MacDonald

was born in Boston in 1966 and grew up in South Boston's Old Colony housing project. He helped launch many of Boston's antiviolence initiatives, including gun-buyback programs and the South Boston Vigil Group, and he continues to work nationally with survivor families and young people in the antiviolence movement.

All Souls

, MacDonald's first book, won the American Book Award and the Myers Center Outstanding Book Award, administered by the Myers Center for the Study of Bigotry and Human Rights in North America. MacDonald is also the recipient of a New England Literary Lights Award. His second book, the highly acclaimed memoir

Easter Rising

, was published in 2006. MacDonald has been a guest columnist for the

Boston Globe

and has just completed the screenplay of

All Souls

for director Ron Shelton. MacDonald lives in Brooklyn.