All That Outer Space Allows (Apollo Quartet Book 4) (6 page)

Read All That Outer Space Allows (Apollo Quartet Book 4) Online

Authors: Ian Sales

Not that it matters, anyway. Even at Edwards, Ginny didn’t feel much like an Air Force wife, a test pilot wife, though she took care to make all the right noises. And this astronaut thing is too new—she’s read books on Mercury and Gemini, she’s seen the photographs of the missions in

Life

magazine, the space walk last year; but a connection between

that

and this room full of smartly-dressed women seems too fanciful to willingly suspend disbelief.

She feels a fraud, perhaps because she dressed up especially for the AWC, and she’s awkwardly aware Walden shares a deeply competitive camaraderie with these women’s husbands which defines all their lives, men and women alike; but she also knows she’s considered little more than some sort of domestic technician by NASA, just another government employee, engineering the home—what’s that phrase in

The Feminine Mystique

? “women whose lives were confined, by necessity, to cooking, cleaning, bearing children”. By

necessity

. There to keep the astronaut home running smoothly, her own wants and needs, her “mystique” not a factor in the equation, not mentioned in any scientific papers or training manuals, not part of the plan to put a man on the surface of the Moon. And return him safely to the Earth.

Much as Ginny would like to avoid the AWC and its monthly meetings, she knows she has no choice.

She is an astronaut wife now.

#

#

Ginny has been thinking about a story, prompted by something she read in a book,

Invisible Horizons

by Vincent Gaddis, a paperback, with a waterspout prominent on its cover, the title above it in bright green letters. Where did she find this book? I don’t know—perhaps she bought it in the Edwards AFB commissary, although I don’t know if they sell books; perhaps it was the same place she found a copy of

Americans into Orbit

, a book store on a weekend trip to Los Angeles, or on a visit to her mother and step-father in San Diego. While I own

Americans into Orbit

, the 1962 Random House hardback edition, I know very little about

Invisible Horizons

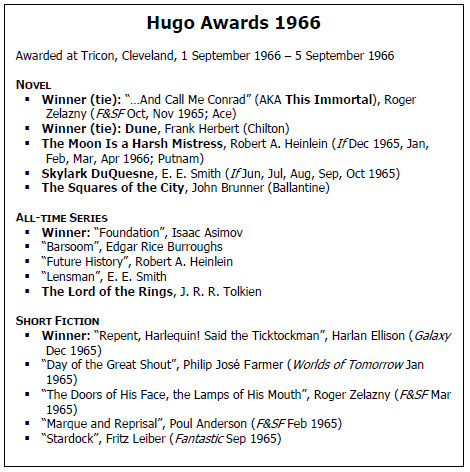

as I’ve not been able to find a copy, I can state only that it was originally published in 1965 by Chilton Books, the same publisher who took a chance on Frank Herbert’s

Dune

in that year. Ginny’s edition of

Invisible Horizons

is the Ace paperback also published in 1965. One chapter in the book caught her interest, an alleged experiment in 1943 to turn a US Navy destroyer invisible—which will later enter occult science mythology on the publication of Charles Berlitz’s book

The Philadelphia Experiment

in 1979, Berlitz being best-known at that time for his 1974 book on the Bermuda Triangle. None of this, of course, is known to Ginny, who has simply happened upon something in a book which she thinks might make a good premise for a science fiction story.

And so she wonders what it might be like to be aboard a ship as it fades from sight while beside her the contractor tries to explain how the house will look once built; but she’s gazing out across an empty plot of land staked out by wooden posts where one day walls and windows and doors and roof will materialise, as if brought into being by the passage of time, and the invisible warship in her mind’s eye morphs into a spaceship. She turns to the contractor, flashes him a smile as if she has heard, understood and agrees with every word he has spoken. As he leads her across the plot toward the dirt road, where his Dodge D Series pickup truck sits behind her Impala, and he swings out an arm and says something about a kitchen, it occurs to her that her story would be more interesting if she told it as

her

story, as a wife’s story. Ginny has stood in a kitchen, wondering if her husband will come home that day, knowing that every morning as he leaves for work he might be killed or injured. She has tried to make a sanctuary for him of their home for that very reason—and for all her independence and need for “mystique”, she loves Walden too much to jeopardise the fragile balance between his work and his home, his sanity and his safety, or even the good standing in which he is held by his current employers.

I guess that’s everything, Mrs Eckhardt? says the contractor.

He pulls open the driver’s door to his truck, and now Ginny can’t see the name emblazoned on it because she’s just come up blank, her head full of story, of an image of herself standing at the stove, and superimposed over it, a ghostly overlay, another woman in some future fashion—perhaps a dress made of small white plastic discs which shimmer and clack when she moves, Ginny thinks she saw something like it in

Vogue

, which of course she does not read herself, it must have been in the beauty parlour, or perhaps when visiting Pam or Mary or Dotty or Joan—

And so she gives another bright smile, puts a hand up to adjust her sunglasses and says, yes, yes, of course, thank you so much.

The contractor holds out a hand to shake, and she looks down at it, briefly disconcerted, and then takes it, his rough workman’s hand enfolding her own with the painted nails she has yet to get used to—the time it takes to keep them shaped and polished!—she feels like she should be a completely different person, not the Ginny whose body she has been inhabiting these thirty years but another person, weak and frail, with her soft red-nailed hands, powder and paint, pantyhose and heels.

It’s all part of the astronaut package. The past few months of parties, the press gatherings, even the television appearance, at all of which her husband has been dutifully accessorized with her, and she has remained polite and noncommittal—but enthusiastic about space, NASA and Walden—they have been exciting times, intoxicating even, after their years of exile in the desert. And the money she has spent so she can look the part! Walden has his new car, but when he demands to know where all the money is going he is blind to the fact she’s wearing a new outfit.

Ginny tells herself all this is fair payment so the man she loves can do what he so dearly wishes to do: go into space, perhaps one day walk on the Moon; but in her increasingly more frequent self-critical moments she knows she’s only fooling herself, making the charade palatable. For the possibility of Walden on the lunar surface, she will keep herself “pretty”, she will dress like the other astronaut wives, she will be thrilled, happy and proud.

And smile until her jaws ache from the hypocrisy of it all.

#

Months later, Ginny will regret her moment of inattention when she learns she apparently agreed to something she doesn’t recall. Walden is furious and believes the contractor unilaterally decided it for himself, but Ginny, if only to deflect his rage, admits it may have been her fault, she had misunderstood or misheard the man. In time, they’ll come to appreciate the contractor’s choice, but for now it sours their pride in their new house, which Ginny feels is only fair since the pride seems to be mostly Walden’s—as if he built the house himself, as if he personally oversaw its construction. She hasn’t the heart to tell him she apparently used the “wrong” contractor, not the one the other astronauts used, and some of the wives have been unpleasant to her about it.

That

sours her sense of achievement.

It doesn’t help that days after breaking ground on the plot in El Lago Walden and Ginny had bought, Gus, Roger and Ed die in a fire in the Apollo 1 command module. Ginny, who knows Betty, Martha and Pat only passingly as fellow members of the AWC, like all of the wives feels the deaths keenly because it seems a tragedy she believed the best of science and engineering worked to guard them against; but now all of their husbands are hostages to the same fickle fortune—and the fact none of them has been able to take out life insurance becomes suddenly and horrifyingly and heart-breakingly

relevant

and

real

. It’s not simply the all too imaginable prospect of a future without their husbands which stabs so deeply, but a stripping from them of their own purpose.

This is not strictly true, of course. At this point in the story, it may be 1967 but women are not chattels, although the Equal Pay Act only became law four years before—a chief campaigner for which was, coincidentally, one of the Mercury 13, Janey Hart. It would be foolish to pretend the United States has actual gender equality. Women had not been given the vote until 1920; and whatever freedoms they may have enjoyed during the Second World War were rudely taken from them when the GIs returned home—as illustrated by the appearance of Ginny’s mother in this story in the previous chapter.

Though it may seem the astronaut wives do little but keep house, mother their children and worry about their husbands, many also have other interests, or even part-time jobs—Rene, as mentioned earlier, is a newspaper columnist, and later becomes a radio host and television presenter; some wives are substitute teachers; others are heavily involved in the activities of their local church or community theatre. But some are indeed only wives and mothers, as Lily Koppel writes in her book,

The Astronaut Wives Club

, about Pat White: “She had dedicated everything to him. She had cooked gourmet meals. She had handled all his correspondence… ‘She just worked at being Ed’s wife,’ said one of the wives, ‘and she was wonderful at it, and that was all…’”

Ginny has years of practice at dreaming up possible futures, but she weeps because Apollo 1 suggests a future she begs providence to keep purely fictional. Walden has always been, and remains still, the brightest star in her map of the galaxy; and she cannot bear the thought of life without him. So she spends days privately weeping for a loss she has not experienced and may never experience; and then she wipes her eyes and fixes her mascara and joins the rest of Togethersville in succouring the new widows.

Later, once the funerals are over and life has returned to what passed previously for normal, although perhaps it is a little more tightly wound, Ginny, who is often inclined to ascribe attributes, either luck or inevitability, to things which do not possess or deserve them, feels the tragedy may blight their new house, might perhaps apply itself to Walden’s career. But she is not a foolish or suggestible woman, if anything she likes to think she sees the world as operating along rational lines, according to fixed physical rules and laws, not all of which have yet to be discovered, a consequence she believes of her choice in literature, of the magazines to which she subscribes, avidly reads and contributes—

Which, sadly, she has not been doing as frequently as she had. Keeping up appearances, showing the other wives she is a reliable member of the community, attending the meetings and parties, dropping by others’ houses, having people drop by hers…

She’s rarely alone, even though Walden is not often at home, he’s either at the Cape all week; or when he’s in Houston, he’s at the Manned Spacecraft Center and when he gets home in the evening his head is too full of orbital mechanics, spacecraft systems and the manuals he has been studying to care about Ginny’s day. It’s a level of disengagement an order of magnitude greater than at Edwards, Walden eats his late dinners in silence, and then spreads all his books and manuals across the kitchen table, or relaxes in front of the Zenith colour television, Space Command 600 remote control loosely held in one hand, to watch the football or a current affairs show.

Perhaps this is just as well. Ginny has been finding it increasingly hard to cope with being an astronaut wife. It has been weeks since she last wore slacks, and her favourite plaid shirt sits folded and unworn in a drawer. The Hermes Baby has only come out of its case a half-dozen or so times since her first meeting of the AWC, and then only to write letters—and she still owes replies to many of her friends.

Since moving to Houston, Ginny has not left the city, she has not been to the Manned Spacecraft Center, she has not seen a rocket or anything related to the space program. Walden has brought lots of paperwork home, and she’s sneaked looks through some of it when he’s not about. But surreptitiously checking out Walden’s training materials—she loves the Apollo spacecraft, their lines, their detail, their immense complexity, all those dials and switches, she wants to know all there is to know, much as she would about a spaceship which appeals to her on the cover of a magazine—but it’s only diagrams and dry text and what she really wants is to climb inside a LM or sit inside a CSM, she’d like to stand beside a Saturn V and actually

experience

its immensity. But she’s reluctant to display too much interest, Walden has professed on more than one occasion that he much prefers his “new” wife, and although she feels like a robot replica of Virginia Grace Eckhardt more and more of the time, in a town of robot wives which were designed, of course, by and for men—and now she thinks about it, that’s not a bad idea for a story—she nonetheless maintains the façade, the pretence: because everything on the home front must be “copacetic” if her husband is to have a chance at the Moon.