All The Devils Are Here: Unmasking the Men Who Bankrupted the World (68 page)

Read All The Devils Are Here: Unmasking the Men Who Bankrupted the World Online

Authors: Joe Nocera,Bethany McLean

On the Thursday before Labor Day weekend, in a meeting with shareholders, Fannie gave reassurances that the government didn’t have anything up its sleeve. The following Friday, September 5, Mudd was summoned to a meeting at the Federal Housing Finance Agency—formerly known as OFHEO—at three p.m. When the Fannie contingent arrived, nobody came to meet them, so they wandered around the lobby. They saw Bernanke come in the front door. They also spotted a

Wall Street Journal

reporter who had been given a heads-up about the meeting. It would have been “almost comical if it weren’t tragic,” Mudd later said.

In a conference room just off his office, Lockhart was seated between Bernanke and Paulson. Lockhart read what appeared to be a script citing one regulatory infraction after another before he got to the real point. Although his team, admittedly, had given Fannie a clean bill of health recently, its capital was sorely deficient and the company couldn’t fulfill its mission. The message, explains one person who was there, was “If you oppose us, we will fight publicly and fight hard, and do not think that your share price will do well with all of the forces of the government arrayed against you.”

Then the government laid out its takeover terms. Existing shareholders of both common and preferred stock in both companies would be largely wiped out. The government would provide no up-front cash, but would put in preferred stock up to a combined $200 billion as equity fell below zero. Fannie and Freddie would be allowed to grow their portfolios through 2009 in order to support the mortgage market, but then they were supposed to begin shrinking them to $250 billion. Freddie, in a separate meeting, agreed immediately. The Fannie contingent at first objected, but eventually realized they had no choice. A government takeover was not easily resisted, not even by Fannie Mae—especially since the government had done one last thing to ensure it would get its way. The GSEs immediately had to fire all their lobbyists, so there could be no running to their friends on the Hill. “Cutting off the head of the snake,” people involved called it.

When Paulson was asked on CNBC about how much money the GSEs would really require, he said, “[W]e didn’t sit there and figure this out with a calculator.”

Paulson would later say that putting Fannie and Freddie in conservatorship was the thing he was most proud of in the crisis. “I knew with great certainty that we were not going to get through this thing without them,” he said.

Paulson had also hoped that the takeover of the GSEs would help calm the growing storm. “I hoped that we’d bring the hammer down and it would be the cathartic act that we needed to get through this,” he later said.

But it didn’t work out that way. If anything, the takeover of Fannie and Freddie only further damaged investor confidence. “The U.S. government, with access to information no private investor could summon, had lured investors into a trap,” Redleaf later complained. “Had the CEO of a private company gone about telling investors that his company had ‘more than adequate capital’ and was in a ‘sound situation’ knowing that the company might be in bankruptcy within weeks, he would have gone to jail for securities fraud.”

The real problem was a little different. The government’s information hadn’t been that much better than anyone else’s, and the government’s optimism was as naive as everyone else’s. And the scale of the losses was simply beyond anything that Paulson had imagined. The takeover of the GSEs shredded some of the last lingering bits of delusion about how bad things really were.

It started all over again on Monday, September 8. Just as Paulson had sensed, Lehman Brothers was the domino. The market that day rose 2.6 percent, but Lehman Brothers dropped $2.05, to $14.15. On Tuesday, the news broke that a last-ditch deal Fuld had been negotiating with the Korea Development Bank had broken off. The stock dropped again. John Thain, Paulson’s old colleague at Goldman who had replaced Stan O’Neal as the CEO of Merrill Lynch, called. “Hank,” he said, “I hope you’re watching Lehman. If they go down, it won’t be good for anybody.” On Wednesday, Lehman preannounced its third-quarter results. It lost $3.9 billion, thanks to a $5.6 billion write-down on its real estate holdings.

That Thursday, September 11, John Gapper, the financial columnist for the

Financial Times

, wrote a column, only half tongue in cheek, with the headline “Take This Weekend Off, Hank.” Noting Lehman Brothers’ mounting troubles, and the likelihood of another long weekend for the Treasury secretary, he wrote, “[W]hen he has worked on weekends recently, the taxpayers have paid dearly.”

Paulson, of course, did work that weekend. Lehman, Merrill, WaMu, AIG—the vultures were circling all of them. Late Friday afternoon, Paulson flew to New York and spent the weekend at the New York Fed, in nonstop meetings with Fed officials and Wall Street CEOs, and they tried to stop what they all saw coming. By Monday morning, Lehman Brothers, unable to find a buyer—or to persuade the government to save it—was bankrupt. Merrill Lynch had been bought by Bank of America. Right behind them came AIG, which would be rescued by the government a few days later at an initial cost of $85 billion.

There was nothing the government, or anyone else, could do to hold it back any longer. Some thirty years in the making, the financial crisis had finally arrived. The volcano had erupted.

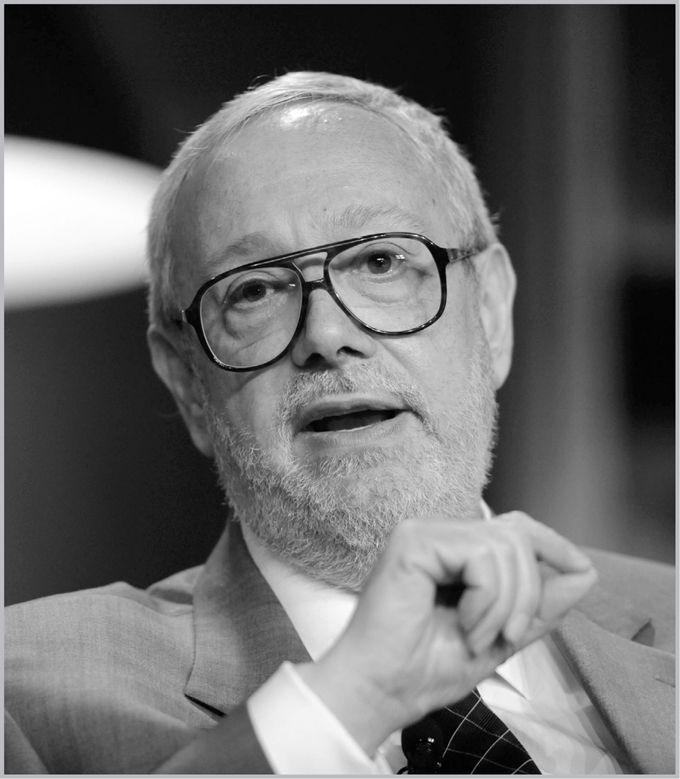

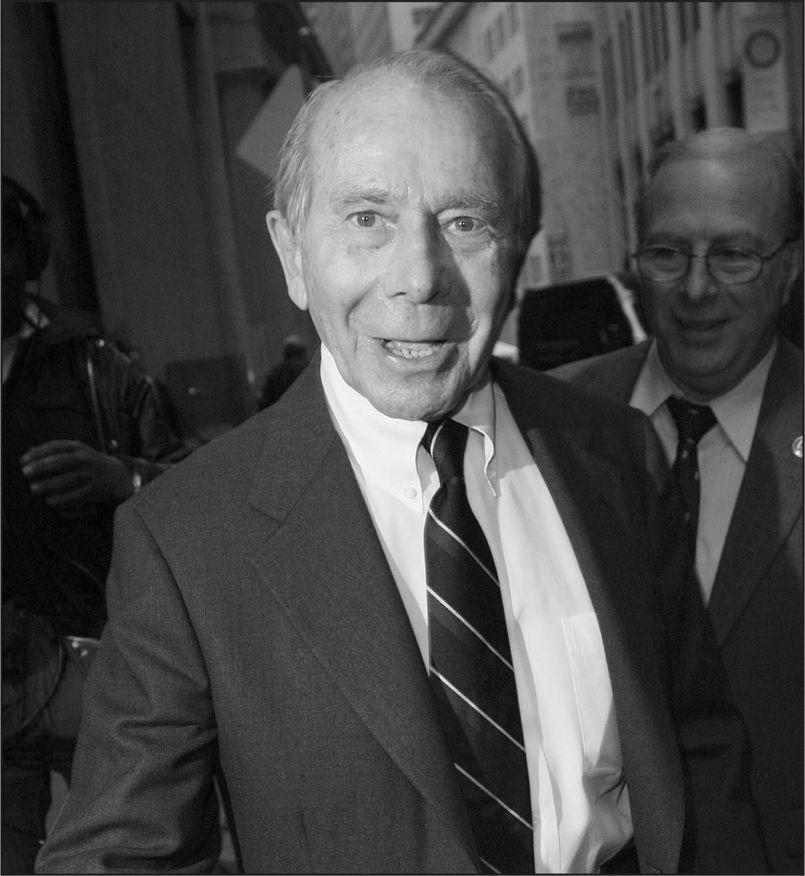

Lewis Ranieri, the Salomon Brothers bond trader who helped invent the mortgage-backed security in the 1980s. “I wasn’t out to invent the biggest floating craps game of all time,” he once said. “But that’s what happened.”

(© Phil McCarten/Reuters)

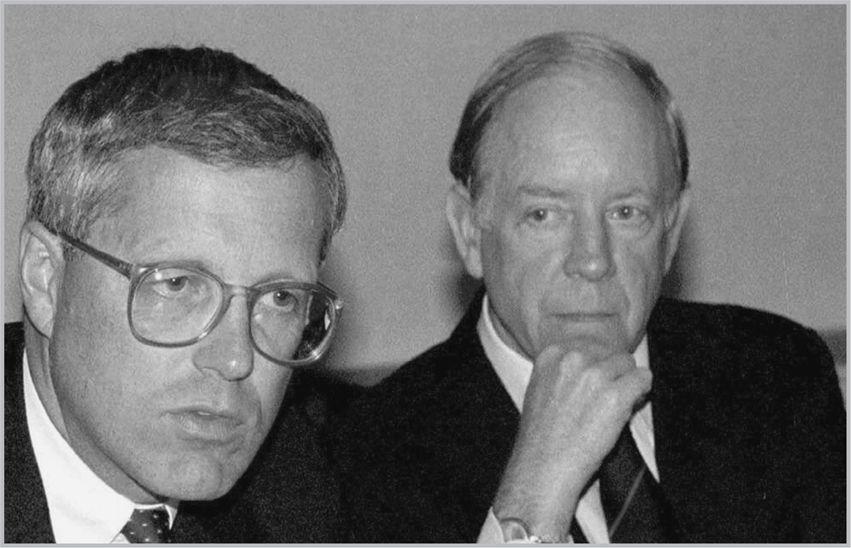

As CEO of Fannie Mae, David Maxwell (right, with future Fannie CEO Jim Johnson) formed an uneasy alliance with Ranieri and transformed his organization into the most powerful player in housing finance.

(© Doug Mills/AP Photo)

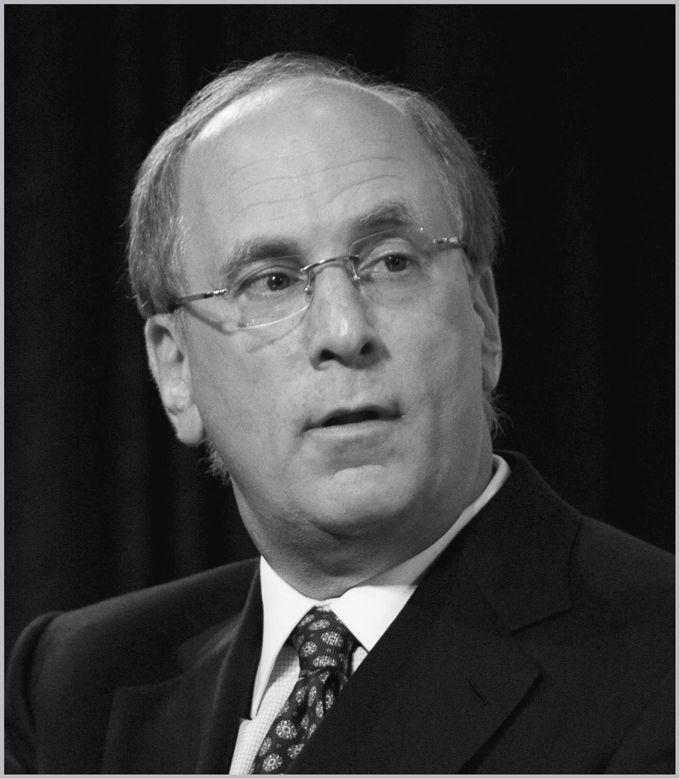

After creating some of the first mortgage-backed securities for First Boston in the 1980s, Larry Fink later served as a key government adviser during the financial crisis.

(© Mat Szwajkos/Getty Images)

Blythe Masters helped invent the credit default swap for J.P. Morgan.

(© Bloomberg/Getty Images)

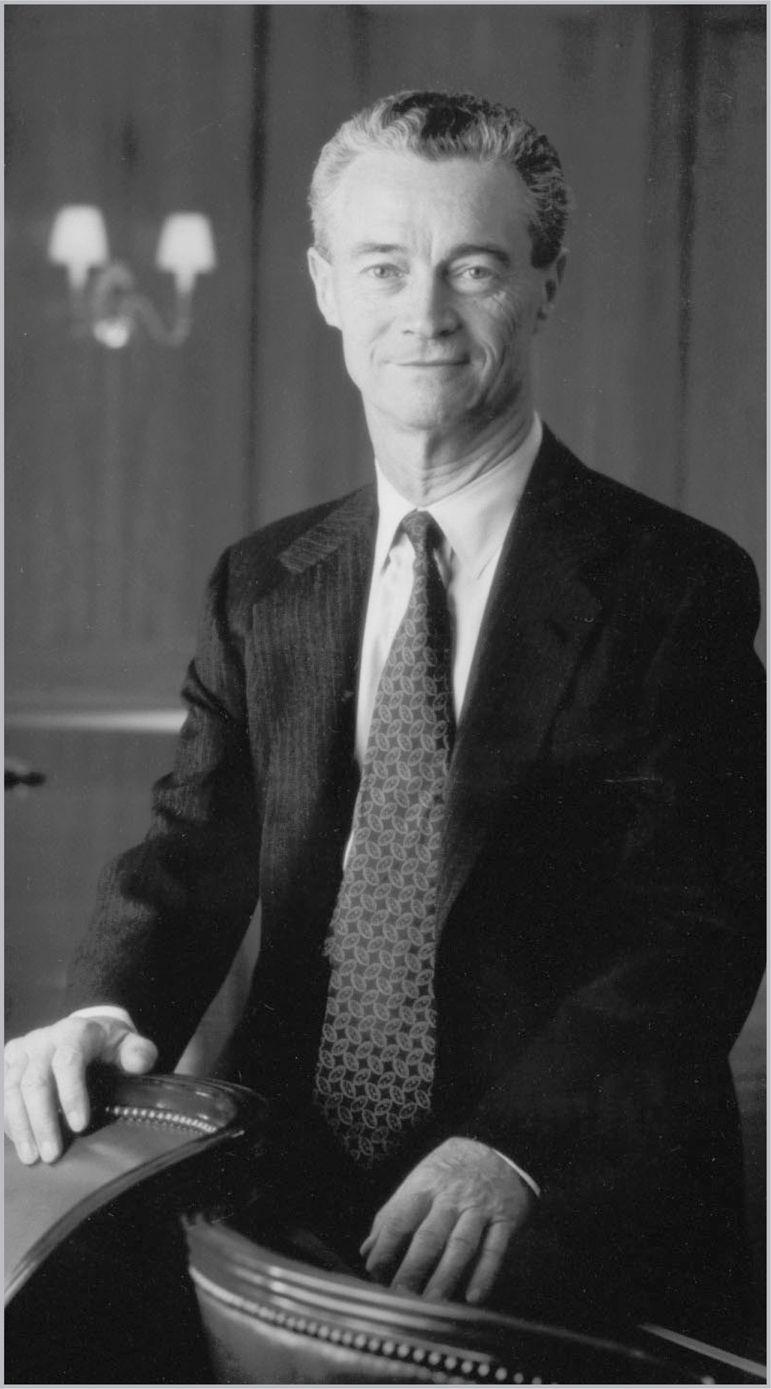

Dennis Weatherstone, J.P. Morgan’s CEO in the early 1990s, wanted an all-purpose risk model that could measure risk across the entire bank. The result was Value at Risk, or VaR, which became the de facto standard on Wall Street. Unlike other Wall Street executives, Weatherstone understood VaR’s limitations as well as its uses.

(© JPMorgan & Co. Incorporated)

Hank Greenberg built AIG into the largest insurance company in the world and appeared to have his finger on the pulse of every one of the company’s hundreds of subsidiaries. But when he was forced to resign in 2005, he left AIG without a viable successor.

(© Bloomberg/Getty Images)