Always Running (34 page)

Authors: Luis J. Rodriguez

Then several hundred FBI agents were sent in to “break up the gangs” involved in the April/May violence—the largest investigation of its kind. Although there were some 600 Los Angeles youth killed in 1991 from gang and drug-related incidents, the federal government never before provided the commitment or resources that they have since the Crips and Bloods declared peace.

At the same time, the immigration authorities terrorized Mexican and Central American immigrants, placing the Pico-Union community under a virtual state of siege (this area was one of the hardest hit in the fires). They deported thousands of heavily tattooed gang members to Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Belize—exporting the gang/cholo culture to countries that had never experienced this level of gang violence.

This is not the first time the federal government has intervened. It has derailed and, whenever possible, destroyed the unity which emerged out of the Watts Rebellion, out of the Chicano Moratorium, out of the Wounded Knee protests. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Black Panthers, the Brown Berets, the American Indian Movement, the Young Lords, the Weathermen, Puerto Rican liberation groups, the Chicano Liberation Front—and more recently MOVE, the Republic of New Africa, FALN, the Black Liberation Army—every major organized expression for justice and liberation was targeted, its leaders killed or jailed, its forces scattered.

To challenge how power is held in America meant facing a reign of terror, some of which I witnessed over the years, most of which failed to reach “mainstream” America—although this is changing. L.A. helped bring it home.

This is the legacy of the period covered in this book. This is what my son, Ramiro, and his generation have inherited.

What to do with those whom society cannot accommodate? Criminalize them. Outlaw their actions and creations. Declare them the enemy, then wage war. Emphasize the differences—the shade of skin, the accent in the speech or manner of clothes. Like the scapegoat of the Bible, place society’s ills on them, then “stone them” in absolution. It’s convenient. It’s logical.

It doesn’t work.

Gangs are not alien powers. They begin as unstructured groupings, our children, who desire the same as any young person. Respect. A sense of belonging. Protection. The same thing that the YMCA, Little League or the Boys Scouts want. It wasn’t any more than what I wanted as a child.

Gangs flourish when there’s a lack of social recreation, decent education or employment. Today, many young people will never know what it is to work. They can only satisfy their needs through collective strength—against the police, who hold the power of life and death, against poverty, against idleness, against their impotence in society.

Without definitive solutions, it’s easy to throw blame. For instance, politicians have recently targeted the so-called lack of family values.

But “family” is a farce among the propertyless and disenfranchised. Too many families are wrenched apart, as even children are forced to supplement meager incomes. Family can only really exist among those who can afford one. In an increasing number of homeless, poor, and working poor families, the things that people must do to survive undermines most family structures. At a home for troubled youth on Chicago’s South Side, for example, I met a 13-year-old boy who was removed from his parents after police found him selling chewing gum at bars and restaurants without a peddler’s license. I recall at the age of nine my mother walking me to the door, and, in effect, saying: Now go forth and work.

People can’t just consume in this society; they have to sell something, including their ability to work. If decent work is unavailable, people will do the next best thing—such as sell sex or dope.

I’ve talked to enough gang members and low-level dope dealers to know they would quit today if they had a productive, livable-wage job. You’ll find people who don’t care about who they hurt, but nobody I know

wants

to sell death to their children, their neighbors and friends.

If there was a viable alternative, they would stop. If we all had a choice, I’m convinced nobody would choose

la vida loca,

the “insane nation”—to “gang bang.” But it’s going to take collective action and a plan.

Twenty years ago, at 18 years old, I felt like a war veteran, with a sort of post-traumatic stress syndrome. I wanted the pain to end, the self-consuming hate to wither in the sunlight. With the help of those who saw potential in me, I got out.

And what of my son? Recently, Ramiro went up to the stage at a Chicago poetry event and read a moving piece about being physically abused by a step-father when he was a child. It stopped everyone cold. He later read the poem to some 2,000 people at Chicago’s Poetry Festival. Its title: “Running Away.”

There’s a small but intense fire burning in Ramiro. He turned 17 in 1992; he’s made it so far, but every day is a challenge. Now I tell him: You have worth outside of a job, outside the “jacket” imposed on you since birth. Draw on your expressive powers.

Stop running.

July 1992

Luis J. Rodríguez (b. 1954) is a poet, journalist, memoirist, children’s book writer, short story writer, and novelist whose documentation of urban and Mexican immigrant life has made him one of the most prominent modern Chicano literary voices. He is perhaps best known for his memoir

Always Running

(1993), a powerful account of his time spent in Los Angeles–area gangs in the 1960s and ’70s.

Rodríguez was born in El Paso, Texas, although his family lived in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, where his parents worked in the public school system. When he was two years old, Rodríguez and his family moved to Los Angeles. Growing up in L.A. and the San Gabriel Valley, Rodríguez was exposed to violence, ethnic tension, and the dehumanizing effects of poverty. He joined a gang not long after the Watts riots of 1965 and became addicted to heroin at a young age. Kicked out of his home, he spent many of his teen years living on the streets or in the family garage. He would later draw on these difficult experiences for much of

Always Running

.

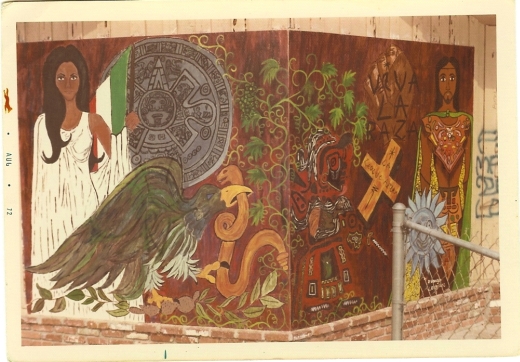

As a teenager, despite his troubled home life and increasing criminal arrests, Rodríguez continued to attend school and developed a strong interest in both art and politics. He rallied against the Vietnam War and helped organize walkouts and protests in high school and the community. He was also commissioned to paint murals throughout his South San Gabriel neighborhood. After community members testified on his behalf during sentencing in a criminal trial, Rodríguez vowed to clean up his life. He quit drugs, attended college classes, and worked a number of jobs to support himself.

In his mid-twenties, Rodríguez began to establish himself as a journalist and writer, producing stories for

LA Weekly

, the

San Bernardino Sun

, and other papers. In 1985 he moved to Chicago and began expanding his literary ambitions. Rodríguez established himself as a fixture in the emerging poetry slam scene, and in 1989 he founded Tia Chucha Press, which published

Poems Across the Pavement

(1989), his first book of verse, as well as the works of other poets in Chicago and throughout the United States. He followed his poetry debut with the collections

The Concrete River

(1991),

Trochemoche

(1998), and

My Nature Is Hunger

(2005) from Curbstone Press.

In addition to writing poetry, Rodríguez continues to work as a journalist and nonfiction writer. He has covered crime, city life, revolutionary politics at home and abroad, Chicano heritage, and other topics for national publications such as the

Nation

and the

New York Times

. With

Always Running

, he captured the attention of readers around the world and become an international bestseller. Rodríguez wrote the book as a cautionary tale for his son Ramiro, who had gotten involved with gangs in Chicago. Since the success of that first memoir, Rodríguez has published more poetry collections, a novel, a short story collection, another memoir, and nonfiction accounts of youth, crime, and recovery. One of Rodríguez’s primary concerns as a writer continues to be the experience of poor immigrants in US cities, a theme reflected in his novels and children’s books as well as first-person accounts.

Rodríguez currently lives in L.A. with his wife, Trini, and their two sons. He also has a daughter and another son from his first marriage as well as four grandchildren.

From left, Luis Rodríguez’s brother Jose Rene (four years old), father Alfonso, mother Maria Estela, sister Ana Virginia (in mother’s arms, a few weeks old), and Luis (age one). This was taken in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. About one year later, the family moved to Los Angeles. Luis’s youngest sister Gloria was born in East L.A. two years after the family moved there.

Rodríguez, age three, with his sister Ana (two), his brother Jose (six), and his niece Ana Seni (one), in Watts, California, 1957.

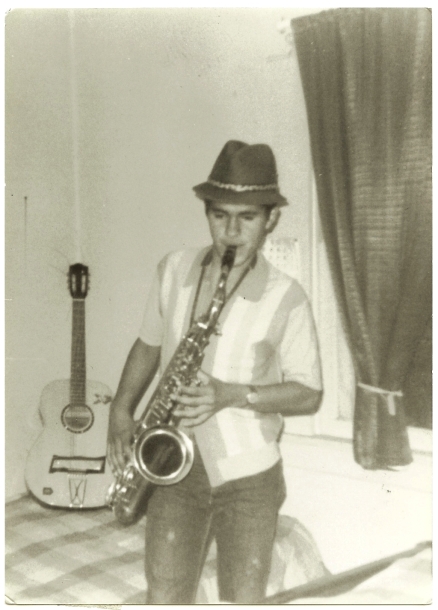

Rodríguez at age thirteen playing saxophone in San Gabriel, California, 1967.

Rodríguez at age thirteen in San Gabriel, 1967.

The first mural painted by Rodríguez, with the mentorship of Alicia Venegas, summer 1971.