Amanda Adams (11 page)

Authors: Ladies of the Field: Early Women Archaeologists,Their Search for Adventure

Tags: #BIO022000

Before the workmen had unloaded their equipment, Nuttall was off by herself scanning the shore for vestiges of the island’s past. She quickly detected a thick, imbedded layer of burnt lime, perhaps a place where it was originally manufactured. Carrying on, she spotted pieces of cement flooring and the base of a wall coated in plaster. She followed the base eastward until she was tracing a now-massive wall that ran east-west. Nuttall’s excitement grew, and as she followed the foundations of an obvious archaeological site, she knelt to the ground and began to tear away soil and roots from the buried surface of a smooth wall. With immense pleasure she noticed that lines painted in red ocher curved along the face of the ancient structure. She put the team to work clearing the area, saving one job for herself: “I reserved for myself the delicate task of clearing the surface of the wall, perceiving as I did so that the red lines formed a fragmentary conventional representation of the feathered serpent, Quetzalcoatl.”

24

It was a great painted dragonish bird with a long history of Mesoamerican worship. Quetzalcoatl is tied to the island’s ritual importance and its role as a place of human sacrifice. Nuttall was eager to reconcile chronicles from centuries ago with archaeological remains, and the appearance of Quetzalcoatl that first day must have seemed a good sign. The accounts she had pulled from forgotten archives describe the scene seafarers witnessed upon arrival at the island before

1510

, including buildings that may have related to Nuttall’s own unfolding discoveries:

We found thereon some very large buildings made of mortar and sand . . . There was another edifice made like a round tower, fifteen paces in diameter. On top of this there was a column like those of Castile, surmounted by an animal head resembling a lion, also made of marble. It had a hole in its head in which they [natives] put perfume, and its tongue was stretched out of its mouth. Near it there was a stone vase containing blood, which appeared to have been there for eight days. There were also two posts as high as a man, between which were stretched some cloths, embroidered in silk, which resembled the shawls worn by Moorish priests, and named ‘almaizares.’

On the other side there was an idol, with a feather in its head, whose face was upturned . . . Behind the stretched cloths were the bodies of two Indians . . . close to these bodies and the idol there were many skulls and bones.

25

Perplexed, the ship’s captain inquired about what had taken place there. Why were the two men dead? Records report that the following answer was given: “. . . it was done as a kind of sacrifice . . . that the victims were beheaded on the wide stone; that the blood was poured into the vase and that the heart was taken out of the breast and burnt and offered to the said idol. The fleshy parts of the arms and legs were cut off and eaten. This was done to enemies with whom they were at war.”

26

By

1572

, the island had a reputation for being haunted by the “spirits of devils.” And by

1823

, another sea captain, an Englishman, noted that the “island is strewn with the bones of British subjects who perished in this unhealthy climate . . .” The Island of Sacrificios always lived up to its name, a destination of sacrifice, and even Nuttall would conclude, “It is strange how, during the course of centuries, the history of the island seems always to have been tragic and associated with some form or other of human suffering and death.”

27

In spite of the morbid past, Nuttall was excited about her project. She made plans to move into an “unattractive and uncomfortable” pair of rooms in an abandoned quarantine station on the island. For a woman in her early fifties, busy as a high-profile socialite, to forsake the comforts of a home she adored for life in the field, she must have been galvanized by the archaeological finds that could be hers. For here was material not bound in a book: it was real, and she could touch it and scrape away the sand to see what came up. Thrilled, she sent Boas a letter in 1910 outlining her plans for a “scientific mission.” She also appealed to government for financial support and was assured that it would be forthcoming. She would receive a stipend of

$

250 toward her expenses.

Nuttall was delighted about her stroke of good fortune. She made plans to spend “some weeks” on the island and looked forward to conducting a thorough exploration of the place, focusing especially on the mural she had uncovered and what appeared to be the temple described in sixteenth-century accounts.

ABOVE :

Zelia Nuttall in her later years

As she made her travel arrangements, Nuttall was walloped by a series of blows. First, the government’s Minister of Public Instruction decided to reduce her funding to only $

100

. It was an impossible amount, completely insufficient to meet her very modest needs. Second, her plan to explore the whole island was now severely compromised: she was told that she would have to confine her investigations to a small portion of the island. And third, the most unbearable, was that Nuttall would now be supervised. Because she was (just) a woman, she would require the oversight of a man: Salvador Batres, the son of an old archrival, Investigator Leopoldo Batres. Batres was notorious for smuggling artifacts from sites he was supposed to be protecting and selling them to foreigners. He also bungled the National Museum’s entire classification system, deciding in his hubris that his predecessor’s work was somehow insufficient (though by Nuttall’s standards, it was quite good). Batres was widely regarded as an arrogant man and, in Nuttall’s opinion, a lousy archaeologist. When the two came into contact, animosity flared.

The announcement read: “ . . . he [Salvador Batres] should supervise her. This Office believes it to be indispensible that he should supervise everything relating to this exploration so that thus scientific interests of Mexico remain safeguarded . . .” Zelia must have choked with anger when she read this. Burning with indignation, Nuttall, the great expert on the island’s history, had been reduced to a mere field assistant, a “peon.” She wrote to Boas that “instead of being helped I was hindered in every way & that conditions offered me were

impossible

to be accepted by any self respecting archaeologist.”

28

Nuttall was incensed, and she resigned from her position as Honorary Professor at the National Museum to show it.

She wiped her hands of the whole affair, but it wasn’t over yet. During Holy Week, Leopoldo Batres sneaked down to the island. A few weeks later the government newspaper published a formal notice that

Batres

had discovered the ruins on the Island of Sacrificios! Nuttall hit the roof. She quickly managed to have an article run in the

Mexican Herald

that drew harsh criticism of Batres’s cocky behavior; she made a fool of him. Referring to this intellectual theft as “the only discouraging experience I have had in a long scientific career”

29

Nuttall began dishing out more shame to Batres, and she dished it out deep.

Her fingers alight with fury, Nuttall wrote a forty-two-page essay for the journal

American Anthropologist,

laying out her years of research, her expert knowledge of the island, her preliminary archaeological work, her theories, her field methods, and so on. The article is considered her most significant contribution to Mexican archaeology. Midway through, she breaks from her calm stream of methodical presentation of facts and finds to lambast Batres and his affiliates. She begins, “Knowing of the trying experiences that other archaeologists, foreign and Mexican, had undergone, I should have rigidly abstained, as heretofore, from having any dealings whatever with the Batres-Sierra coalition . . .”

30

She had the attention of every anthropologist and archaeologist in North America reading the popular journal, and she used it to devastating effect. Not only did she ruin Batres’s career, she humiliated the administration that had enabled him, noting with matter-of-fact coolness that it was no wonder this “coalition” had discouraged modern science and driven all true archaeological talent out of Mexico.

Just when the lynching seems complete, Nuttall sharpens her claws and rips into Batres again, this time criticizing his entire classification scheme for the museum’s archaeology department with a string of embarrassing examples. Señor Batres was destroyed, finished. In contrast, Nuttall’s reputation not only had been restored but was now brighter than ever. Everyone knew she was in the right. As a later obituary for her attested, “Mrs. Nuttall’s vivid mind, independent will, and a remarkable belief in the truth of her theories caused her life to be punctuated with controversies.” She was drawn to a good fight like a moth to light.

IN A DAY

when there were hardly any women working in scientific fields, Zelia was regarded as “the very last of the great pioneers of Mexican archaeology.”

31

She was one of the great pioneers to be sure, but most notably she was the only woman on a roster of men. She was prolific in her scholarly interests and pursued everything from the universalism of the swastika to archaic culture to ancient moon calendars. Over time some of her work has fallen into disuse—new material has proved old theories wrong, recent discoveries have revamped once trusty chronologies. Yet a large portion of her work is still relied upon today for its accuracy and erudition. It was Nuttall who decoded mysterious codices, who brought manuscripts to light, and who was able to unite disparate strands of research on Mexican artifacts and sites. Before she settled into life at Casa Alvarado she traveled extensively—collecting artifacts in Russia, navigating archives in Italian libraries—and even as a new bride, Nuttall lived the life of an anthropologist, debating questions of ethnology and ethics over breakfast.

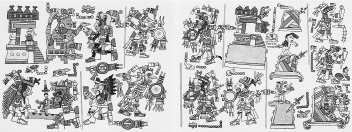

ABOVE :

The Codex Zouche-Nuttall, one of Zelia Nuttall’s most important discoveries

What drew Nuttall to archaeology is a question that can be whittled down to an even finer point: what drew her to Mexican archaeology? For all her interest in world history, Nuttall’s relationship with Mexico was deeply monogamous. Nuttall’s path toward archaeology was illuminated when her mother handed her the picture books, when she first met the serpent Quetzalcoatl as an eight-year-old.

All of Nuttall’s personal letters have been lost, and with them any personal expression of her passion for the field.

32

But one has only to look at her life: marriage, separation—Mexico (as if to seek inspiration at a difficult time); Europe, motherhood, a return to California roots and then a refusal, a seduction—Mexico again. Nuttall stayed in her beloved Mexico and Casa Alvarado until the day she died, in 1933 at age seventy-five. Her love affair with the country was best expressed through archaeology. It allowed her to engage with the past, present, and future of the land and culture she adored. She dug into its soil and found pieces of its heritage, she nurtured her native plants from volcanic soils littered with prehistoric ceramics to watch them bloom each spring, and she published her research and recommendations broadly to help inform preservation of Mexico’s heritage for the future.

Nowhere is Nuttall’s love for Mexico, past and future, clearer than in her article titled

The New Year of Tropical American Indigenes,

written toward the end of her life, in

1928

. Through it, Nuttall seeks to restore indigenous Mexican culture to its living heirs. Aware of what was lost when the Spanish tore through and conquered the country, Nuttall was an early advocate for the revival of “Indian” traditions. She calls upon the poetics of the solar cult to breathe history’s legacy into contemporary life with a traditional celebration of the indigenous New Year. She begins by explaining how in a region

20

degrees north and south of the Equator, “a curious solar phenomenon takes place on different days, according to the latitude, and at different intervals. In its annual circuit the sun reaches the zenith of each latitude twice a year, near noontime, and when this happens no shadows are cast by either people or things.”

33